In Imola, Italy, a team of archaeologists unearthed a rare case of "coffin birth". The study of the bones made it possible to trace the causes of the death of the mother and the post-mortem "delivery".

The discovery and analysis of the bones of a burial showing a case of coffin birth highlights medical knowledge in the 7th century AD.

In 2010 in Imola, near Bologna (Italy), archaeologists made a discovery that left them perplexed. They unearthed a tomb dated to the Lombard period, in the 6th-7th centuries AD. The body of a woman lay there and the bones of a fetus were visible between her legs, partly caught between the pelvic bones of the deceased. Like an unfinished childbirth frozen in death. A team of researchers from the Universities of Ferrara and Bologna published on February 15, 2018 in the journal World Neurosurgery an analysis of the bones.

Decomposition gases causing the expulsion of the baby

When she died, the mother was between 25 and 35 years old. Measuring the length of the fetus' femur determined that he was 38 weeks old. So the mother was two weeks away from her due date. Her baby did not survive her. This is a rare case of "post-mortem fetal expulsion" or "coffin birth" named after the place where it most often takes place. Today, this phenomenon is rare in our latitudes, but it still occurs in the fields of forensic medicine or, as here, archeology. When a pregnant woman dies, the gases of decomposition invade the abdominal cavity. After a period of two to five days, the pressure of these can end up expelling the baby from the uterus. Pushed by the gases, the baby comes out by the most natural way, although the pressure can sometimes prove to be too weak. In the absence of muscle contractions, the child then remains partially in the body of its mother.

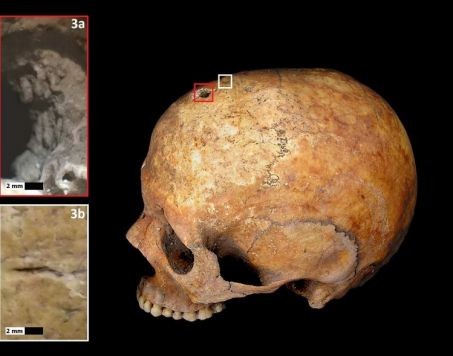

But the scientists' analysis helped to more accurately reconstruct the events that led to this discovery. And in particular the causes of the death of the mother. It was a small circular hole nearly 5mm in diameter on the top of his forehead that put them on the path. A nearby mark reveals that the young woman underwent trepanation. This very delicate surgical operation has been known since the Neolithic period. It consists of drilling a hole in the cranial box using a drill bit. A technique that inspired the one currently used to remove brain tumors or evacuate blood during subdural or epidural hematomas (in the brain). Trepanation was known and practiced in Italy during the Lombard period.

Mother's skull shows signs of trepanation. Pasini et al./World Neurosurgery

The young woman survived her operation as shown by the traces of healing from her wound. It wasn't the trephine that killed her, but researchers are linking her pregnancy to the operation she underwent. According to their hypothesis, she probably had an attack of eclampsia, a convulsive crisis due to hypertension brought on by the pregnancy. "Because trepanation was once used in the treatment of hypertension to reduce blood pressure in the skull , they write,we hypothesized that this lesion may be associated with the treatment of a hypertensive pregnancy disorder." In an attempt to cure her of her eclampsia, the doctors of the time therefore chose to operate on her, hoping to save her and her baby. Unfortunately, the operation did not alleviate the mother's illness. Eclampsia is fatal if the pregnancy is not terminated immediately and abortion is the only treatment. The woman died carrying her child. And the natural process of decay meant that she finally gave birth in the grave.