The ravages of pandemics have also had an impact on art. Thus the Black Death gave birth to the 15 e century to very codified performances, called Danses macabres. Appearing in France, they will become a recurring theme in European painting illustrating the egalitarian nature of death in the face of epidemics.

"Danse macabre" adorning one of the walls of the former Saint-Robert abbey church in La Chaise-Dieu (Haute-Loire).

If the coronavirus resuscitated in the collective unconscious the images of the Spanish flu of 1918 as much as those of the black plague from 1347, the most terrible of the medieval epidemics was itself at the origin of phantasmagorical creations which crossed the time. Thus among the most famous of these artistic manifestations, the appearance of strange sarabands on the walls of religious buildings in the 15th century. Dating from this period, the former abbey church of Saint-Robert de La Chaise-Dieu (Haute-Loire), for example, still preserves on one of its walls the funereal icon of death clutching the arm of the deceased carried away by the sickness. The lanky skeleton - which appears for the first time in France - tramples their poulaines. Hilariously, he tripped, pushing the humans unceremoniously, hastening their fall. Among the twenty victims drawn into the lugubrious dance, we recognize - petrified with terror - a pope dressed in purple, ecclesiastics, a plump merchant, clerics, a swaddled child, a minstrel, a canoness, a constable, un ploughman.... A sinister choreography, the Danse macabre, as these performances were named, is a theme directly linked to the eruption of the "black death" in the West. The plague.

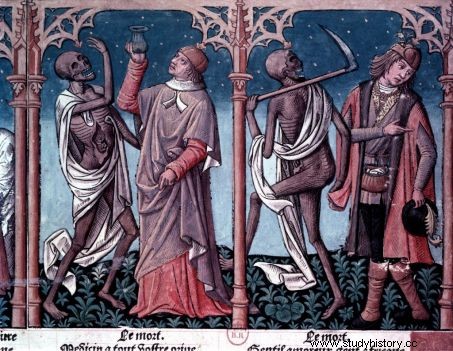

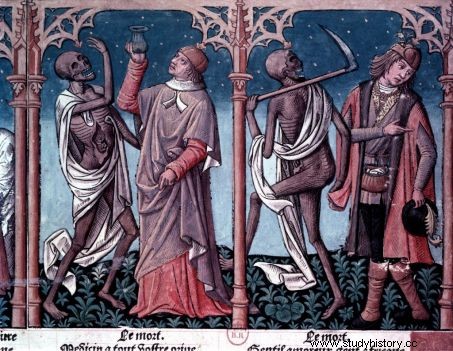

The mournful sarabande of the Danse macabre, in the 15th century. © Josse/Leemage/Afp

This pandemic is coming to France in a bruised and already decimated kingdom. In the 14th century, in fact, the population suffered the brunt of the trauma of the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) when the ruthless epidemic of bubonic plague or black plague caused by the bacillus Yersinia pestis spread. . This landed on November 1, 1347, from the holds of three ships docked in Marseille. They arrive from Caffa, a Genoese trading post located on the shores of the Black Sea (Crimea). In 1348, Venice was reached. In less than a year, the entire perimeter of the Mediterranean basin was affected. It has been calculated that the plague progressed by 30 to 100 km per month, and that the pandemic caused the death of at least a third of the European population, or approximately 25 million victims.

No one knows from then on which saint to devote oneself to. Death is everywhere. In France, not a family, not a city, not a region, is spared. The corpses are so numerous that they cannot be buried. They litter the streets, the sides of the roads and decompose in plain sight. The Church will seize on this catastrophe to show the inexorable and egalitarian character of death which strikes without distinction of social condition, age or sex. Who was in great shape the day before, dies struck down the next day. And in these times of religious beliefs, the punishment is necessarily divine. This idea is the very driving force behind the “danse macabre”. Whether one is rich or poor, young or old, male or female, the plague devastates everything in its path. It maintains the eschatological anxieties of the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment. When these dances appear in 15th century painting, the theme is already known in literature, in the form of a poem, in particular the "Said of the Three Dead and Three Living" , a dialogue between the living and the dead that recalls the inescapable human condition:"What you are we have been. What we are, you will be one day ."

First appeared in the books, a Danse macabre illustrating the Bible of King Charles VII (1403-1461). ©Snark/photos12/AFP

This representation of death, whose allegory was in the 12th century a character with bat wings or the fourth horseman of the Apocalypse, will also evolve.

If the coronavirus resuscitated in the collective unconscious the images of the Spanish flu of 1918 as much as those of the black plague from 1347, the most terrible of the medieval epidemics was itself at the origin of phantasmagorical creations which crossed the time. Thus among the most famous of these artistic manifestations, the appearance of strange sarabands on the walls of religious buildings in the 15 th century. Dating from this period, the former abbey church of Saint-Robert de La Chaise-Dieu (Haute-Loire), for example, still preserves on one of its walls the funereal icon of death clutching the arm of the deceased carried away by the sickness. The lanky skeleton - which appears for the first time in France - tramples their poulaines. Hilariously, he tripped, pushing the humans unceremoniously, hastening their fall. Among the twenty victims drawn into the lugubrious dance, we recognize - petrified with terror - a pope dressed in purple, ecclesiastics, a plump merchant, clerics, a swaddled child, a minstrel, a canoness, a constable, un ploughman.... A sinister choreography, the Danse macabre, as these performances were named, is a theme directly linked to the eruption of the "black death" in the West. The plague.

The dismal sarabande of the Danse macabre, at 15 e century. © Josse/Leemage/Afp

This pandemic is coming to France in a bruised and already decimated kingdom. At 14 th century, in fact, the population suffered the brunt of the trauma of the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) when the relentless epidemic of bubonic plague or black plague caused by the bacillus Yersinia pestis spread. . This landed on the 1 st November 1347, the holds of three ships docked in Marseilles. They arrive from Caffa, a Genoese trading post located on the shores of the Black Sea (Crimea). In 1348, Venice was reached. In less than a year, the entire perimeter of the Mediterranean basin was affected. It has been calculated that the plague progressed by 30 to 100 km per month, and that the pandemic caused the death of at least a third of the European population, or approximately 25 million victims.

No one knows from then on which saint to devote oneself to. Death is everywhere. In France, not a family, not a city, not a region, is spared. The corpses are so numerous that they cannot be buried. They litter the streets, the sides of the roads and decompose in plain sight. The Church will seize on this catastrophe to show the inexorable and egalitarian character of death which strikes without distinction of social condition, age or sex. Who was in great shape the day before, dies struck down the next day. And in these times of religious beliefs, the punishment is necessarily divine. This idea is the very driving force behind the “danse macabre”. Whether one is rich or poor, young or old, male or female, the plague devastates everything in its path. It maintains the eschatological anxieties of the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment. When these dances appear in the painting of the 15 th century, the theme is already known in literature, in the form of a poem, in particular the "Said of the three dead and three alive" , a dialogue between the living and the dead that recalls the inescapable human condition:"What you are we have been. What we are, you will be one day ."

First appeared in the books, a Danse macabre illustrating the Bible of King Charles VII (1403-1461). ©Snark/photos12/AFP

This representation of death, whose allegory was in the 12 th century a character with bat wings or the fourth horseman of the Apocalypse, will also evolve. At 13 th century, it became a cantilever reaper, before being represented in the 14 th century, in the – unequivocal – form of a corpse, replaced by a dead body from 1420, like the unfinished fresco at La Chaise-Dieu (Haute-Loire). It is interesting to note that these artistic conventions follow the evolution of knowledge. Anatomical knowledge has indeed progressed. The dissections practiced in Italy since 1340 were in turn authorized in France by Pope Clement VI. This ex-monk of La Chaise-Dieu who became pope in 1342, present in Avignon during the plague epidemic of 1348, will seek to understand, by studying the bodies, the origin of the terrible disease. He will authorize their dissection for analysis, which Christianity, in the name of the belief in the resurrection of the flesh, had not permitted until then. From poem to fresco, the first dance of death will be represented in Paris, in 1424, on a wall of the mass grave in the cemetery of Saints-Innocents. Its dazzling success will lead to the production of numerous replicas, not only in France but also throughout Europe.

Medieval danse macabre adorning a wall, in Italy. © Leemage/AFP

In 1440, Dances of Death adorn the walls of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, then it will be around the churches of Lübeck and Dresden (Germany), Vienna (Austria) or Lucerne and Basel (Switzerland) to be decorated. At 18 e century, finally, the terrible jig has exhausted its frenzied rhythm. The Renaissance and the Enlightenment having passed through this, the Danses macabres and their grimacing figures will eventually disappear from the repertoire of religious iconography.

When death was represented by volleys of arrows. © Wikimedia

From the "black death" to the "danse macabre"

Prior to the 15th century, epidemics like the plague were depicted in art as the "black death," a volley of arrows falling on humans. With the "Danses macabres", the performance will involve around thirty characters presented according to a well-established code:pope, emperor, cardinal, king, patriarch, constable, archbishop, knight, bishop, squire, abbot, bailiff, master , bourgeois, canon, merchant, Carthusian, sergeant, monk, usurer, doctor, lover, priest, plowman, lawyer, minstrel, friar, child, cleric and hermit. And death itself, in the form of a skeleton or transi.

The original of this article was published in issue 726 of Sciences et Avenir magazine