Post-mortem manipulations of human bodies are documented in many parts of the world. Recent work in the Chincha Valley, Peru, looks back on 200 cases of human vertebrae strung on reed stems. An act that could reflect a reaction to the destruction of the colonial period.

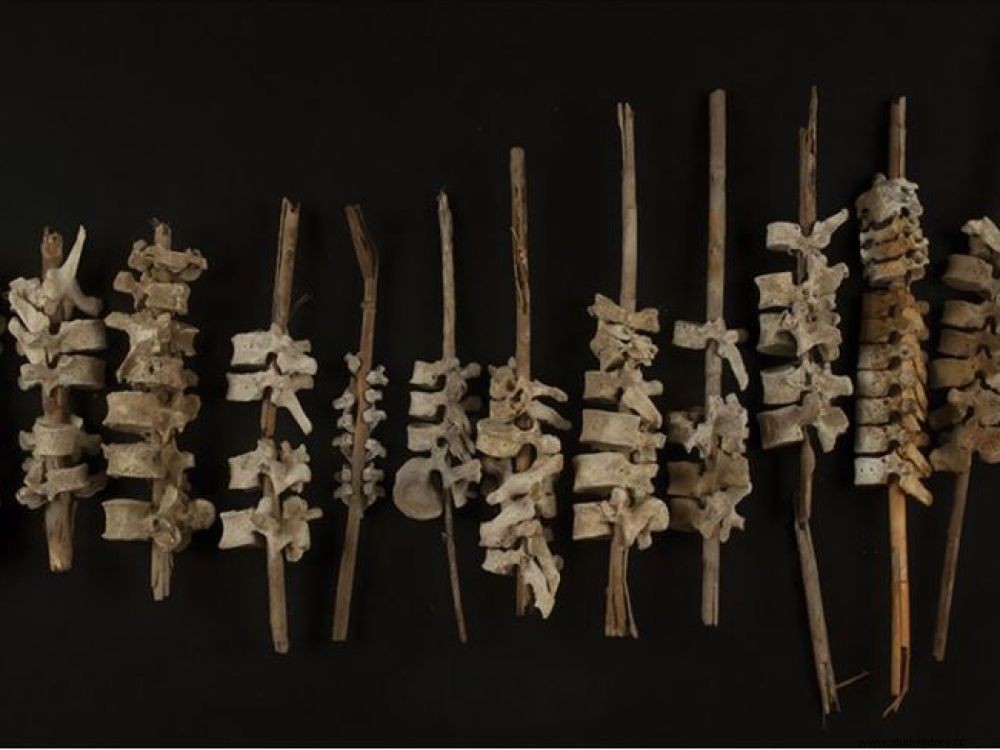

Examples of vertebra skewers found in tombs in the Chincha Valley, Peru.

It is a curious sight that archaeologists discovered in the Chincha Valley, in Peru. Located 200 km south of Lima, this region already known for its giant geoglyphic traces, like those of the Nazca lines, has recently been talked about for all other finds. Anthropologist at the Sainsbury Research Unit at the University of East Anglia (UEA) in the United Kingdom, Dr. Jacob L. Bongers has indeed come across burials where human vertebrae have been strung on reeds like the pearls of a necklace on a string. All in an attempt to reconstruct what, one day, were spinal columns. A description that was published in the journal Antiquity after the examination of more than 500 tombs and the study of 192 of these assemblages.

Carried out on 79 of these "skewers of vertebrae" collected from around twenty archaeological sites, the radiocarbon dating of these human remains gave ages oscillating between 1520 and 1550 AD, the harvest of the reeds dating from 1550 to 1590. This time gap is essential to understand the completely original theory proposed by Jacob L. Bongers, the main author of the study.

a) Vertebrae on reeds inserted into a skull, as found in a chullpa; b) annotated photograph showing the arrangement of the lumbar (L), cervical (C) and thoracic (T) elements on a reed. Credits:J.L Bonger/ Antiquity

"Nothing should be offered incomplete to the sun"

First of all, the territory on which these burials were located was that of the Chincha kingdom, incorporated into the Inca Empire around 1400. And the turbulence generated by this integration only worsened with the arrival of the Spaniards in 16th century. According to the Antiquity article , the epidemics (several episodes between 1546 and 1558) and the famines (1539-1548) which followed, led to the death of many inhabitants, giving rise to their burial in tombs called chullpas . Driven by an irrepressible thirst for gold, as soon as they arrived, the European conquerors rushed to these funerary monuments to strip the bodies of the deceased of their precious objects, ransacking the ordering of the skeletons, and therefore their anatomical integrity.

Now the Andean peoples had a great veneration for their dead. "Nothing should be offered incomplete to the sun" , recalls the archaeologist. Confirming these profanatory practices, the Sevillian chronicler Pedro Cieza de Leon (1520-1554) relates thus:"There was an enormous quantity of tombs in the hills of this valley. And many of them were opened by the Spaniards to remove large sums of gold ". Faced with this abomination that was the rape of graves, Jacob L. Bongers then wondered if the local populations, by reburying their dead after the passage of the Spaniards, had not attempted to literally "reconstitute" the backbone of the remains, by replacing their vertebrae (cervical, thoracic and lumbar) on stalks of reeds. This could have characterized a sort of ritualized act of resistance against the looting of the colonizers.

The hypothesis of "rattles" used in rituals and ceremonies

The fact that the bones are older than the reeds and that the date of these reeds coincides with the period of colonization may well support this hypothesis. Other suggestions have also been offered:they could be "rattles" used in rituals and ceremonies, or even war trophies consisting of bones taken from enemy bodies. DNA analyzes could soon be carried out to determine whether the chullpas inside which these "restorations" were found were family graves or mass graves.

It should also be noted that this use of "threading the vertebrae" was also not completely unknown in the Andes. Thus, some Chinchorro mummies (10,000 - 4,000 years old; they are the oldest in the world) unearthed on the coast of Peru, in the Atacama desert, sometimes had a stick skewered through the vertebrae to maintain rigidity of the trunk. Pipes however separated by thousands of years.