"How were the Nazca lines drawn?" , asks a reader on our Facebook page. This is our Question of the Week.

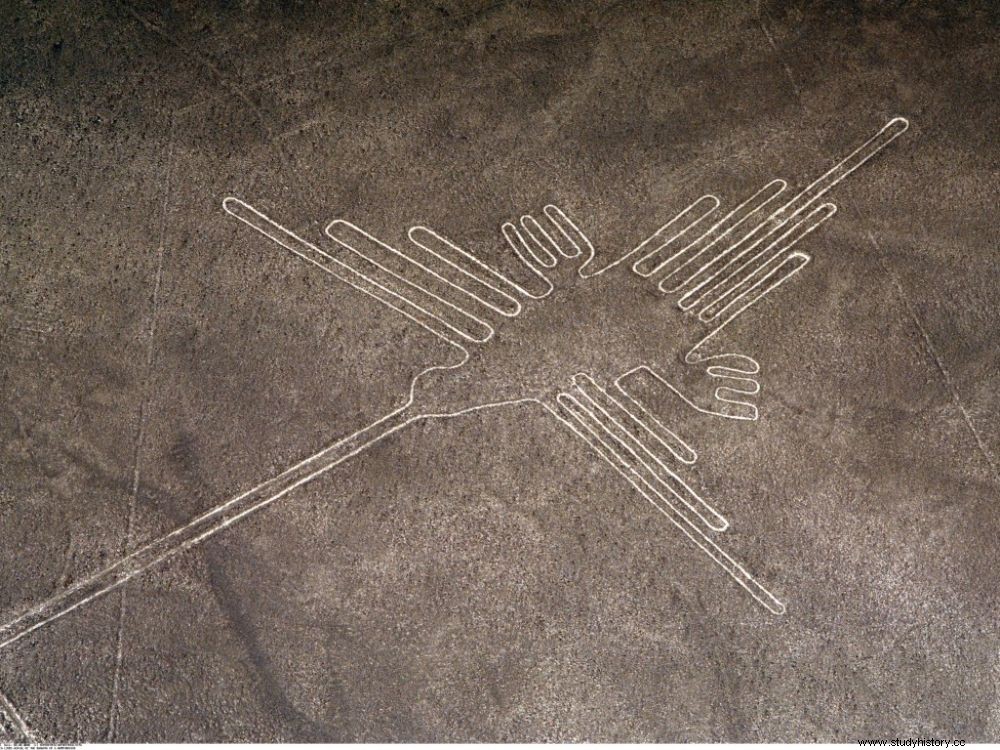

One of the famous Nazca geoglyphs.

"How were the Nazca lines drawn?" , asks the editorial staff of Sciences et Avenir Louis Mongrain on our Facebook page. This is our Question of the Week. Thank you all for your participation.

The Nazca Lines, giant figures made by communities of farmers

The Nazca lines, also called "Nazca geoglyphs", are grandiose arabesques traced by the Nazca civilization which flourished at the foot of the Andes between the 3 th century BC and the 7 th century AD But also in some cases, by their predecessors, the Paracas, farmers who lived in this same region between 800 BC. J.C and 200 after J.-C. The originality of these populations is to have traced on the ground of the desert these strange assemblies - representations of human beings, plants or animals in particular - which did not cease to inflame the spirits.

Works carried out successively by communities of farmers for 1,500 years, hundreds of these effigies scarify the Peruvian desert. Executed on land that iron oxide colored gray, they were made by scraping the surface layers of the stony ground, to bring out the lighter gypsum levels located below. Why ? How did they do it? During the excavations carried out in recent years, the mystery has gradually been cleared up. Skilled weavers, accustomed to handling long threads, the Nazcas used ropes, manipulated from fixed points, to draw their figures. They were inspired by the same motifs as those that adorned their pottery or the precious textiles that made them famous. A reality far removed from the fanciful assumptions that were made in the middle of the 20 e century to explain these giant drawings, some not hesitating to evoke landing strips for extraterrestrials... The geoglyphs would be linked to agricultural calendars, to a complex irrigation system, and to places of ritual worship dedicated to different deities. They may also be territory markers.

Processed image of a "two-headed serpent" and two human figures. Credits:Yamagata University / IBM Japan

Hundreds of geoglyphs discovered in recent years

In 2019, Japanese scientists from Yamagata University identified the presence of 143 geoglyphs in the arid pampas of Nazca and Jumana, 400 kilometers south of Lima, Peru. Hardly visible to the naked eye because of their gigantism, and especially the erosion that erases them over the years, these monumental patterns were identified from high-resolution images and 3D laser scanner recordings made in 2018. Representations of human beings, plants and animals such as snakes, fish, birds and llamas have thus been distinguished. Very satisfied with the results, the researchers plan above all "to continue to use artificial intelligence to search for new figures". In 2018, about thirty other figures north of Nazca had been discovered by Peruvian teams, including one conducted in the Palpa Valley, by Aïcha Bachir-Bacha, Andean archaeologist at the School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS) , in Paris (read Sciences et Avenir n°861 ).

Comparison between the image detected in the plain of Nazca, and the features identified by the AI. © Yamagata University / IBM Japan

These geoglyphs, listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1994, remain very fragile due to the threat posed to them by the proximity of certain urban areas. Remember that the figures and "lines" of Nazca, Palpa, Ica or Chincha, the different valleys and plains in which they are found scattered over some fifty kilometers, are not unique on the American continent:other geoglyphs also exist in the desert in northern Chile, as well as a few others in North America.

A century of prospecting

Mentioned from the 16

e

century by the Spanish chronicler Pedro Cieza de Leon (1250-1254), the alignments and figures of Nazca were mainly unveiled from 1927 by Peruvian aviators. Prospected from 1939 by the American anthropologist Paul Kosok, but it was with the work of Maria Reiche, a German mathematician who arrived in Peru in 1932, that these Cyclopean drawings became universally famous. Like Paul Kosok, she had seen in these geoglyphs instruments for measuring the movement of the stars. In 1926, a Peruvian anthropologist named Toribio Mejia Xesspe had seen in these alignments a system of sacred paths taken during ceremonies. Hypothesis today shared by the majority of specialists.

By Bernadette Arnaud