Jack the Ripper can hide with them with his miserable achievements. William Hunter and William Smellie, respected fathers of obstetrics, textbook authors and genius pioneers in the field of gynecology were at the same time ... ruthless murderers. How many victims do they have on their account? More than thirty pregnant women and their children. They had them killed in the name of science.

William Hunter wrote the groundbreaking work "Anatomy of a Human Pregnant Uterus with Drawings" , and also studied the uteroplacental-fetal circulation. Years later he became the personal physician of Queen Sofia Charlotte Mecklenburg-Strelitz and professor of anatomy at the Royal Academy.

William Smellie created the obstetric phantom for educational purposes, designed innovative obstetric forceps, described the mechanism of delivery and published the textbook "Anatomical Chart Set with Explanations and Summaries of Obstetrics Practice". They both lived in 18th century England and they both amazed the scientific community.

Two highly respected doctors

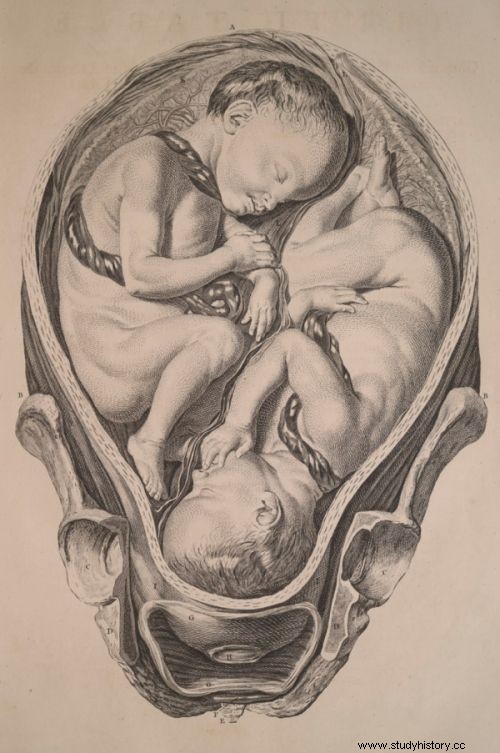

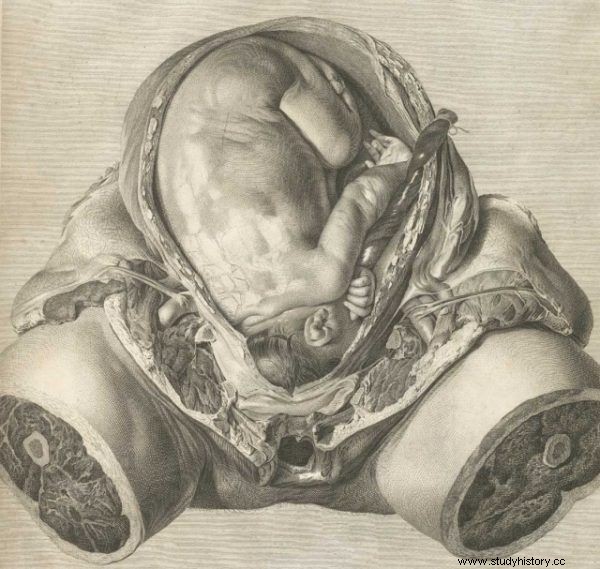

The quality of the drawings and the mapping of anatomical details in their books was amazing. These materials can be easily compared to modern photographs taken by forensic pathologists.

The question that the investigative team from the "Bones" or "CSI" series would surely ask themselves here is:how could doctors working in an era devoid of modern technology achieved a similar effect?

Bloody mystery of a classic work

For two and a half centuries, no doubt, the reliable work of Hunter and Smelli has served generations of anatomists, gynecologists and obstetricians. Subsequently, they gained a reputation as works of extraordinary historical value as Hunter and Smellie became the "fathers of British obstetrics" and their merits began to be entered in every possible encyclopedia.

A peaceful drawing? Only until you start asking questions about how it came about…

However, there were no inquisitive detectives. And no one asked where exactly two doctors had obtained more than thirty bodies of women in advanced pregnancy and whether all the corpses were for sure obtained in an ethical manner. Perhaps it was taken for granted that two respected doctors would not resort to undignified methods.

Too few dead bodies

One of the widespread stereotypes about life a few centuries ago is the belief that death has taken an extraordinary toll on pregnant women. In London, in the mid-18th century, the mean maternal mortality rate up to a few days postpartum, when the risk of infection is considered the highest, was only around 1.4%.

This data is supported by later general statistics for London in 1837 when compulsory registration was introduced. Not surprisingly, Don Schelton of the Royal Society of Medicine estimated the probability of recovering a pregnant woman's corpse at 7-9 months in the mid-18th century at 0.1%.

So our two doctors would need many years of hard work as cemetery hyenas to get the number of "patients" we need. Inevitably - they chose a different method.

One of the pathologists is failing?

The first suspicions arose at the beginning of the 19th century, and at the source:based on the anatomical atlas of Hunter and Smelli. Table X in their publication shows the twins. In 1818, Joseph Adams wrote in relation to this case:

Below is a note from Mr. Hunter regarding this paragraph.

"Dr. MacKenzie as assistant to the deceased Dr. Smellie, providing and carrying out the autopsy of the woman without Dr. such discoveries cannot be kept secret.

The following winter Dr. MacKenzie began teaching obstetrics at the Borough, Southwark. ”

This text was not published until Dr. Hunter's death.

The cited paragraph and the words "direct steps" clearly have meaning in the case. They can be interpreted very simply:as an admission by John Hunter that the woman had been murdered. "Direct steps" refers to what the assistant did to perform an autopsy. The "cannot be kept secret" section, on the other hand, implies that questions have arisen as to how the unfortunate research subject died.

William Huner. The father of medicine or a criminal? Maybe both.

Since it was not the method of the doctors' work that was a secret (after all, the preparation of corpses was a process that was already widely used), then it must have been a crime covered with a secret.

Colleagues will always help

Soon after the revelation that the "fathers of British obstetrics" could be ruthless butchers emerged, the scientific community, and especially the medical community, reacted with holy indignation.

It has been argued that the accusations are unfounded and the evidence is insufficient. Some defense attorneys argued that the tables in Hunter's and Smelli's works depicted the same fetuses, that some fetuses were in different stages of development, and that some of the tables were based on earlier, already existing drawings or preparations.

Others wrote that maternal mortality at a time when both doctors were carrying out their research was able to obtain sufficient cadavers through ethical methods. A stormy discussion among contemporaries is still going on, and a summary can be used by William Hunter himself.

Illustration from Smelli's anatomical atlas. What was the price of his discoveries?

He stated in the introduction to his controversial work that:

[…] the chance of an autopsy on a human pregnant uterus is very rare. Indeed, if this does happen to anatomists, it is at most once or twice in their lifetime .

So blind fate had to be helped. For the sake of science!

Bibliography:

- Janette C. Allotey, William Smellie and William Hunter accused of murder… , "Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine," vol. 103 (5), May 2010.

- Peter M. Dunn, Dr William Hunter (1718–83) and the gravid uterus , "Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition ”, vol. 80 (1), 1999.

- Peter M. Dunn, Dr William Smellie (1697-1763), the master of British midwifery , "Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition ”, vol. 72 (1), 1995.

- Matthew F Kaufman, Nigel A Malcolm-Smith, The Emperor's new clothes , "Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine," vol. 103 (5), 2010.

- Wendy Moore, Case not proven , "Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine," vol. 103 (5), 2010.

- Roberts, A.D.G., Baskett, T.F., Calder, A.A., Arulkumaran, S., William Smellie and William Hunter:two great obstetricians and anatomists , "Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine," vol. 103 (5), 2010.

- Don C Shelton, The Emperor's new clothes , "Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine," vol. 103 (5), 2010.