Alcohol for centuries has been and is an inseparable companion of soldiers at the front and its back. It allowed you to forget, to react, it was soothing, it killed the boredom of waiting. During the Polish-Bolshevik war, soldiers from both sides did not pour out by the collar.

The vast majority of Polish soldiers fighting in the Polish-Bolshevik war and participating in the international intervention in Russia were veterans of the Great War - experienced and brave in battle, but also traumatized. Alcohol or ether made it possible to reduce the level of stress associated with experiences in the battlefield. That's why people drank in the back. On the other hand, on the front lines, alcohol helped to overcome fear.

While in the rear, drunkenness was not tolerated - it was chased by the field gendarmes, so on the front line they turned a blind eye to this practice. Provided, of course, that the soldiers did not exaggerate. And they did it quite often. So much so that in some cases half of the companions were sent on guard.

In the partitioning armies, alcohol was part of the food ration. For example, in Austria-Hungary, the daily allowance for one soldier contained half a liter of wine. The regulations allowed them to be exchanged for three-quarters of a liter of beer or for one hundred milliliters of high-proof alcohol. . Cognac, rum or vodka were mentioned as substitutes. It was nothing strange. Especially the latter was part of everyday life. The then statistical Galician peasant drank 17.2 liters of vodka a year. It was similar in the tsarist and kaiser armies. So much so that Toruń was called a "fortified pub".

Drinking out of boredom

It wasn't easy to wean the soldiers from partying. Alcohol combined with boredom was often the cause of turmoil. Especially since the authorities of the new country did not always know what to do with, for example, seamen. After the creation of the Polish Navy and the Department for Maritime Affairs, the Chief of the General Staff of the Polish Armed Forces, Gen. Stanisław Szeptycki and Col. Jan Wroczyński, the then head of the Ministry of Military Affairs, despite their best intentions, had no idea how to deal with this problem. So they were subordinated to ... the Department of Aviation.

The sailors were placed in the Modlin fortress, where there were no entertainment. So they killed boredom with alcohol. Unfortunately, this led to arguments more and more often. In late November 1918, several drunken sailors beat up the intervening policeman. Another time the sailors attacked the owner of the premises, who refused to serve them their drinks and then kicked everyone out and served themselves. It ended in a rebellion, "requisition" of the train and a trip to Warsaw. The situation was calmed down only by the respected naval commander, Colonel Mar. Bogumił Nowotny.

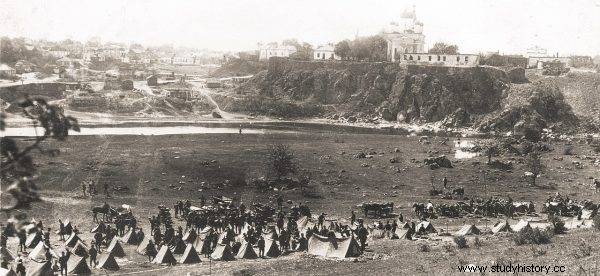

Polish soldiers near Kiev in 1920

Both privates and officers were bored. The command complained that "you can see too much free time and too much money all those military, who spend long hours drinking wine alone or with women of light manners, and often with Germans". Officers, having more cash, could go crazy, but it also happened that the balls stretched and the cash disappeared.

In some cases, a restaurant was introduced to a Dow. Headed receipts with the seal and signature of individual commanders, displayed for food and even wine. I note that when officers receive a subsistence allowance, they must pay it themselves in cash; issuing receipts in these cases is not allowed and will be punished.

Even the soldiers serving in the great garrisons had a long time. So what could Poles say at distant posts. The soldiers of the Murmansk Battalion drank both in the blockhouses on the front line and in the rear in Arkhangelsk. They drank with allies, alone and with women, telling about the adventures of the march to Murmansk:

He continued to drink on the way, and because he got bored on a ship on the Volga River, he seduced Krasawica, the wife of one of the highest Bolshevik commissioners, members of the St. Petersburg government. When the next day the ship was searched, the captain left his quarters in the corridor and shouted to the commissioners:"They're gone!" It is not known what the case would have ended if, at the lion's roar, the seduced commissar had not jumped out of the neighboring cabin and repeated the order of her accidental lord and ruler.

The hero of this story was Captain Kazimierz Hrakałło-Horawski, who was famous not only for his incredible courage on the front line, but also for the fact that he never refused. He could drink - and he drank, as befits a cavalryman. Even in the face of the enemy.

At the front

On the front lines, people drank both for courage and stress, as well as for entertainment. Especially for meals. There was a difference, however. Some units were privileged and better provisioned. Especially those the Commander-in-Chief had an eye on.

In Szarkowszczyzna stood the command of the 1st Regiment of Szwoleżerów. I went to check in. Perhaps ten officers sat in the headquarters, none of whom I knew. They all ate some wonderful canned goods, meats, fish and other completely non-war delicacies, heavily washing them down with vodkas and liqueurs. For me, an infantryman, it was something completely new, because in our regiment, and probably also in many other infantry regiments, no one indulged in such things.

All the officers ate from the soldier's cauldron, from the same canteens as the soldiers, and nibbled on bread with the same as them. Not only did we not have any sophisticated liqueurs, but it was also quite difficult to get ordinary vodka in an officer's canteen. At best, it was a smelly moonshine, commonly puffed in huts in the borderlands.

In Polesie, Volhynia and Podolia, you could find moonshine in practically every cottage. That is why the soldiers used the "gray hair" almost every day. Lt. Mar. Karol Taube recalled that one morning Lt. Just after waking up, Jan Giedroyć asked a short question:“Uf, I overslept, ho! ho! ho! The sun is up… or maybe you've spotted some "land" on the horizon - aa - he yawned loudly - cold. One to warm up. What?". Of course the answer was yes.

As a reward

Vodka was common. You could get it anywhere and for pennies. And often even as a reward. When the Cavaliers returned to Warsaw after the capture of Vilnius, they were duly welcomed in the capital:

A hail of flowers and cigarettes poured out on the soldiers in Nowy Świat. When they were driving to Krakowskie Przedmieście, bottles of vodka were distributed. This is important, a real Polish ball, only the jumble is missing! In front of the Church of the Holy Cross, some of the soldiers forgot to take off their caps because, putting the bottles to their mouths, they were frying vodka.

Pawlik Drank to Furmanek, gave Turowski a treat, and just in front of the Church of the Visitationists the "zechcyka" begins. Turowski was very interested in the game, he accidentally turned onto the sidewalk and did not enter Bristol by a little trick. (...) At the corner of Trębacka street, there are baskets of vodka and snacks again.

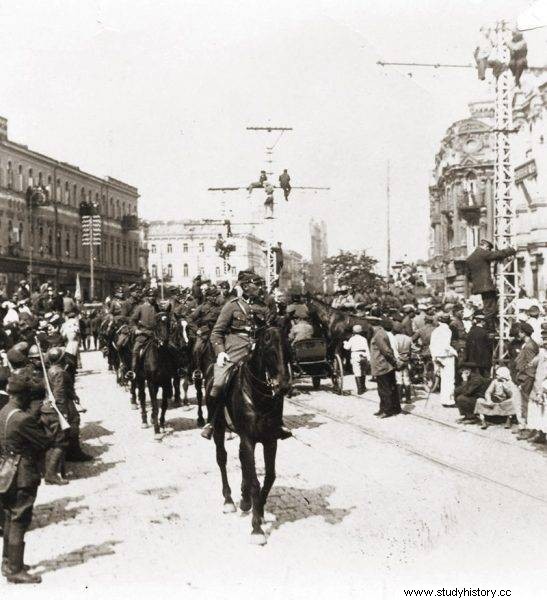

The winners were often greeted with vodka (in the photo:parade in Kiev).

This is how the winners were greeted! Soldiers were also cherished in the provinces. After the battle of Horodyszczem, the crews of the armed cutters were given a three-day pass to Pinsk. The sailors spent this time drinking and having fun in the company of young ladies. Augustine, the sailor, who after the capture of the Bolshevik commissar became a hero, drank in excess and plunged into women's breasts. Everyone kept queuing him and slapped him on the back. The officers also indulged themselves. Although they had to quickly return to the reality of war, those carefree days were still remembered for a long time.

Captured vodka

Sometimes it was necessary to save the alcohol from the approaching enemy. Cf. pil. Marian Romeyko and 2nd Lt. obs. Józef Sieczkowski, airmen of the 3rd Intelligence Squadron, had to make an emergency landing. They sat down with their breguet in a field near a large estate. It turned out that it belonged to Aleksander Szeptycki. There was quite a large distillery on his estate.

(...) was just getting ready to leave and ... horrendum, to release all the spirit of the distillery straight into the ditches. The next day we received gasoline and, together with Sieczkowski, we loaded a huge bowl of pure spirit and two ducks into the spacious observer's seat!

I never started off with as much care as we did then . The bubble with the spirit was not corked and it steamed straight into Sieczkowski's nose. When we arrived at the airport near Lublin, he was completely dead , and while still in flight, over the airport, he threw both ducks "so that they would fly too." There was a lot of fun in the squadron; it was decided to always send me on similar "missions".

Sometimes, however, it was better not to drink alcohol that was found, obtained, or obtained. During the Third Silesian Uprising, seamen from the Assault Division, Lieutenant Mar. Robert Oszek, they found a large supply of vodka in an inn in Lichynia. The commander forbade them to consume the prey. He was right. The schnapps turned out to be poisoned.

For soldiers, vodka was a stepping stone, and sometimes a measure of normality. The problem of high alcohol consumption was noticed not only by senior commanders but also by social activists. Maria Moczydłowska, a well-known activist of the women's movement and president of the "Sobriety" Society, came up with the idea of introducing prohibition in barely reborn Poland.

The suffragette thundered from the parliamentary tribunal that alcohol is "a poison to society" and that the introduction of prohibition would not harm the budget, but health would improve, and the moral backbone of society would strengthen. The military did not mind her ideas at all. Alcohol poured in streams regardless of any prohibitions.

Bibliography:

- Czyż N., Diary of the Polish-Bolshevik War of 1919 and 1920 , Poznań 1919.

- Franaszek P, Diet of the Galician peasants at the turn of the 20th century, [in:] Annals of social and economic history, vol LXXVI, 2016.

- Kaden-Bandwski J., Cwałem, Gallop. Tales from the Bolshevik War, OW Modem 1990.

- Kopański T.J., 3rd Intelligence Squadron 1919-20, Warsaw 1994.

- Smoliński A., Alcohol in the Greater Poland army in the light of the orders of the main command from 1919, [in:] Alcohol in the army and in war. From the history of Polish and general military , ed. A. Niewiński, Oświęcim 2018.

- Zagórski S., White versus Red. Polish sailors in the war against the Bolsheviks , Krakow 2018.

- Fragments of the book being prepared Baśka Murmańska and Lwy of the North were used, S. Zagórski.