In the 18th century, superstition reigned over medicine among the rural population. Fortunately, there was a doctor who decided to improve the knowledge of the "commoners".

Whether Ludwik Perzyna had formal medical education - it is not known, although taking into account the activities and views he promotes, it can be safely assumed that he did. He was born in Krakow in 1742, and already as a doctor he practiced in Podolia, Pokucie, Wallachia and Spisz. Later he moved to Warsaw, where he joined the Order of the Brothers of Mercy.

Fighting the tangle improved hygiene in modern Poland

He wrote much more about medicine than religion. On the one hand, he was a source of long medical practice, and on the other hand, the works of other medics read and translated :Austrian Störck and Swiss Tissot. It was the second author who inspired Perzyna to direct efforts to spread knowledge among the lower strata of society.

Read also:Hygiene of medieval queens. Did our rulers stink?

For the owners

A work of ninieysze for the Peasants of our Nation, following the example of the old Council for the Swaycar Society, published by P. Tyssot, now written by me, properly offered to anyone, I do not think, how YOU are GENTLY LORD Farmers, tees are the Worker Classes, the whole human nation needs yeshy.

- Perzyna asked metropolitan canon Jan Szeynert about the most important of his works:"A doctor for peasants, or advice for the common people." This book, dedicated to the least educated social class, was intended to improve general health and combat poor medical practices in the countryside. What could be found on the pages of the work?

Perzyny's tips may seem fairly obvious today. The doctor emphasized the need for moderation in eating and drinking, and promoted healthy exercise and hygiene. It must be remembered, however, that these were not yet common views:in schools, for example, it was taught that frequent washing is ... harmful to health!

Having noticed, following the example of his authorities, that diseases were transmitted between people in various ways, he also proposed limiting the possibility of their transmission. According to Perzyna, soldiers returning from the front should be checked by a doctor before they are released among people - it was mainly about venereal diseases, which the soldiers used to readily pass on. Therefore, patients should be kept in the infirmary until symptoms are gone.

Contents of the "Doctor for the peasants"

Perzyna put great emphasis on ending paramedical practices commonly used among peasants, arguing that only properly educated people should be allowed to pursue the profession of a doctor or pharmacist.

[...] the long-established trust in Jews, and the reliability of treatment in women, peasants and oleikers, to pass it on, having this from experience that, as with you, also in the higher class of people, prejudices come, only many will want to find out that a doctor, that is, a scientist, must be incomparably more adept in his art than the above-mentioned idiots [...]

- he wrote to all kinds of charlatans and quacks. He also promoted a way of thinking "without images", that is, based on facts and research, instead of folk beliefs and messages. In the absence of a doctor in the area, Perzyna suggested that his work be purchased by the local parish, where a priest who could read could pass the knowledge contained therein to the faithful in need. However, according to Perzyna, it was not the only role of clergymen in maintaining good health in the society. One of the most important tasks that the friar set for himself was…

Fighting the tangle

The entire first chapter of "The Doctor for Peasants ..." is devoted to combating tangling. In his opinion, priests or doctors working in military recruitment should be held responsible for removing knots, and care for hygiene is key in the fight against the disease. Perzyna recommended, which was a complete novelty in his time, bathing even once a week!

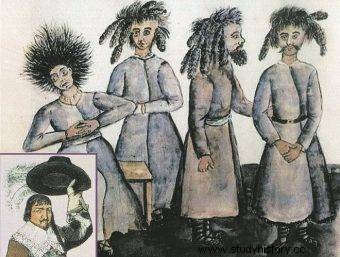

Tangled was indeed quite common in the 18th century, although it is not a disease in itself - tufts of hair stuck together, resembling dreadlocks, appeared on human heads not only due to hygienic negligence, but also through sticking together with various secretions (appearing, for example, with head lice) or by wearing a cap all the time (which was a popular habit among peasants). Regardless of the causes of the tangling, Perzyna's recommendations are just as right as ... funny.

A drawing of a woman with a tangle, 18th century.

He divided the tangles into two types, changing the previous classification taken from other doctors. He distinguished between true and untrue knots - the first ones self-tie, even when combed out, in one night. If it did not, it was a false tangle and could be easily cut off. The real thing shouldn't be done like this:you had to wait for the hair to grow by itself and the glued part to separate from the skin and fall off. The reason for this classification was the fact that alcohol was recommended according to folk knowledge as part of the treatment of knotweed. so many "sick" cheated by deliberately tangling their hair with wax and tar and then wandering from door to door asking for a "cure".

Perzyna attributed the occurrence of one true kind of knot in Poland to the climate. In remote regions of the world, the scholar believed that tangles occurred in different varieties and could be caused by other factors, such as different types of air or food. In his opinion, the reason could also be the spread of salt from Wieliczka and Bochnia, because the mineral contains a lot of "harmful pungency". Therefore, while foreign doctors suggested drinking borscht, cold soup or eating beetroot and chard as part of treatment, Perzyna additionally recommended more frequent baths and combing of hair. He based these recommendations on observation:among the wealthier Muscovites and Jews who bathed every Friday, tangles were the least common. Meanwhile, in poor oil-bearing regions like Galicia, tangle of tangled hair was a common sight. Although Perzyna did not know the true causes of the tangling, his advice was very correct!

Read also:Pure sinner and dirty saint. How often did women bathe in the Middle Ages?

In healthcare

Ludwik Perzyna was so remembered in the fight against the tangle that he called for fighting it by state organizations - the police, in his opinion, were to cut "false" knots, and priests were to make sure that the faithful did not try to smuggle bundles of braided hair under their caps.

The longest preserved knot is in the Museum of the Faculty of Medicine of the Jagiellonian University, dates back to the 19th century and is 1.5 m long after unfolding.

Although it all seems amusing in retrospect, Perzyna's teachings could have contributed to a significant improvement in medical care in Poland. The clergyman also promoted humane treatment, consistent with Christian ethics, for the mentally ill (he even created a separate classification of these diseases, in which we find, for example, "smutnodur" as a term for melancholy), as well as education of all social strata.

Unfortunately, his teachings were forgotten for a long time due to the ongoing wars and partitions. The fight against tangles - ultimately victorious - was later undertaken by Alexander Antoni Le Bruno, a doctor specializing in this field, who, from 1862, ordered obligatory cutting of hair tufts before being admitted to the hospital.

Read also:Did our great-grandmothers use pads? Hygiene in pre-war Poland

Bibliography:

- Perzyna, L., A doctor for peasants, that is advice for the commoners in diseases and ailments of our country, either appropriate or for the greater part assimilated, is needed by every inhabitant of our country. Kalisz, 1793.

- Matusiewicz, H., Brother Ludwik Perzyna (1742-1800) a doctor and writer in the Bonifrater's habit:in 2010, the anniversary of the death of brother Ludwik Perzyna and in the year of the 400th anniversary of the presence of the Order of Bonifraters in Poland. Warsaw, the Polish Province of the Hospitaller Order of St. John of God, 2010.