There is not enough seats in the great hall of the Parisian court around noon. At 1 p.m., when the last day of the trial of Polish actress Stanisława Umińska begins, the room is filled to the brim with the audience. There are representatives of the Polish diaspora, ordinary French, there are also journalists from popular Parisian newspapers. The trial of Stanisława Umińska excites the capital of France - there is great love, great suffering, crime of love and there is still art in this case.

From her stage debut in 1919, Stanisława Umińska was considered a revelation and hope for Polish theater. Shortly after her first performance on the stage of the semi-amateur Promenada Theater, she was hired by the Polish Theater in Warsaw. After her outstanding role as Orcia in Krasiński's Nie-divine Comedy in 1920, critics recognized Umińska as one of the most talented actresses of the young generation.

A year later, she starred in the movie "Major Barbara". Her roles of Cherubino in "The Marriage of Figaro" and Elf Knock in Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream" were long remembered by critics. She has confirmed her outstanding comedy and drama talent in over twenty roles. She created her last theatrical performance in April last, 1924.

Jan Żyznowski on the Montparnasse boulevard in Paris. The photo was taken just two days before he went to the hospital, where Umińska cut short his torment.

Artist in uniform

Two years ago, Stanisława Umińska met Jan Żyznowski at one of the openings. The handsome 34-year-old famous painter, critic and writer was a distinguished combatant in the fight for independence. Before the World War II, he studied painting and literature in Paris, he belonged to the Society of Polish Artists in Paris. After the outbreak of the war, he joined the Polish armed forces on the Seine, which had been formed since August 1914. As a result of Russian protests, instead of the planned Polish Legion, a unit of less than 200 volunteers was formed in the town of Bayonne. After training, the pioneering Polish troops incorporated the French into their Foreign Legion as the 2nd company of the 1st Legion Regiment.

Many outstanding Poles, including artists, fought in the ranks of the fiery company. Two of them, Xawery Dunikowski and Jan Żyznowski, designed the company banner, presented to the soldiers at the end of September 1914 by the mayor of Bayonne.

After the French command was liquidated, as a result of protests by the Russian Embassy, a separate unit of Polish volunteers, Żyznowski left in 1915 for St. Petersburg. There, for a long time during the war, he cooperated with the editorial office of the "Głos Polski" daily. He used his fights in the Foreign Legion as early as 1916 in his memoirs "To Poland with Joffr". In the same year, he published a collection of short stories.

It was Jan Żyznowski together with Xawery Dunikowski who designed the banner of the "fairy tales". The illustration shows a fragment of Jan Styka's painting "The death of Władysław Szujski in the battle of Sillery".

At the end of the World War, Żyznowski arrived in Warsaw. In 1919, his geometric, expressive, dark color compositions were decorated with the Polish Futurists Club in the Hotel Europejski in 1919. During the Polish-Bolshevik war, Żyznowski once again went to the battlefields as a volunteer.

After the victory, it turned out that he is a multi-talented artist. He quickly made a career as a popular, influential journalist and art critic in Rzeczpospolita, Tygodnik Ilustrowany, and Wiadomości Literackie. He published three volumes of prose, based on memoirs from the battles of 1914 and 1920. Especially "Bloody Shred", published two years ago, was considered by readers to be a true testimony of the war times. The authenticity of the realities, despite the Young Poland manner of "Strzęp", delighted also the critics.

The article was also published as one of the chapters of the latest book by Włodzimierz Kalicki, entitled "It happened" (Znak Horyzont 2014).

One last request to my wife:kill me

The fiery romance of such popular artists aroused widespread interest in Warsaw. However, a year and a half ago, doctors diagnosed Żyznowski with incurable cancer. The painter, who was suffering terribly, decided to seek help from doctors in Paris. His wife without hesitation left the Mały Theater, where she celebrated successes in Charles Dickens's "Świerszcz Behind the Chimney", and left with Żyznowski to France.

However, the Paris specialists were helpless. Umińska constantly looked after her tormented husband, by all means obtained more and more morphine to suppress his suffering. In short moments of the patient's well-being, she wrote down the novel "Z podlebia" dictated by him.

On July 15 last year she succumbed to Żyznowski's pleas to reduce his suffering. In the afternoon she gave him a morphine injection, and when he fell asleep - she shot him in the temple with a pistol. At the same moment she passed out.

The facade of the Parisian hospital where Stanisława Umińska killed her terminally ill husband.

Before the trial, the accused was declared by the authorities of the Polish and French bar. The outstanding lawyer Gustaw Beylin came from Warsaw.

Prosecutor on the defendant's side

Even before the trial, it was clear that the sympathy of not only the public, not only the defenders, but even the prosecutor was on the defendant's side. The prosecutor Donnat Guigne prepared the indictment very restrained, in fact being a camouflaged justification for the act of the Polish actress. Guigne emphasized in it that Umińska was an exceptionally sensitive person and tormented by the torment of her beloved, and that Żyznowski's health did not bode well for improvement.

The prosecutor also mentioned in the indictment that on July 12 last year Umińska spontaneously donated her blood to doctors to save Żyznowski. The chairman of the jury, Judge Mouton, conducted the questioning of witnesses with ostentatious sympathy for the accused.

Nurses from the hospital and a friend of the defendant, Mrs. Gottlieb, testified that they had witnessed Żyznowski pleading with Umińska to spare him suffering and to kill him. The head doctor of the hospital in which the tragedy took place, Dr. Roussy, told emphatically how the actress looked after her loved ones with great dedication. After the testimony of Dr. Roussy, Umińska in the courtroom thanked him for everything he had done for both her and her lover. At the end of her speech, the female part of the audience started sobbing with emotion.

Judge Mouton agreed that the letter of the outstanding Polish sculptor August Zamoyski, absent from the court, be read. Umińska's act was a testimony to her dedication to Żyznowski and, at the same time, a testimony of her obedience to her beloved, who had a great influence on the actress, wrote Zamoyski. The testimony of a medical expert made a great impression on the audience. Dr. Paul stated that, to his knowledge, Żyznowski could still live, naturally in torment, no more than eight days.

Umińska seemed absent during these testimonies. Silent, apathetic, she acted as if the proceedings did not concern her.

At the time of the trial, the sympathy of the public and even the prosecutor and chairman of the jury Mouton was entirely on the Umińska side (standing first from left).

Today, on the last day of the trial, the prosecutor takes the floor first. Donnat Guigne begins by stating that in this case he would rather be a defense attorney than a prosecutor because Umińska's case is not a crime story, but a legend of great, beautiful love. The ladies in the room are crying.

The legend of beautiful love

The prosecutor recalls the vicissitudes of Umińska and Żyznowski's life and relationship. When he talks about shooting a terminally ill person, he chooses words and phrases that, in his opinion, the actress seems to be more of a savior than a killer. Donnat Guigne admonishes the jury that the accused is a foreigner, so her psyche has many secrets beyond the French mind. Please bear this in mind, gentlemen, when you pass judgment, the prosecutor thunders.

Finally, the prosecutor consciously notices that the real problem in Umińska's case is not the verdict - here he implies that the accusation in fact awaits acquittal - but the fear that the uniqueness of the story, the widespread sympathy for the defendant, could allow the public to suppose that the murder of abolishing suffering is permissible.

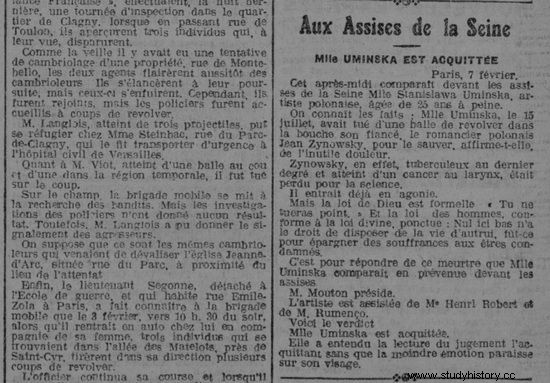

Umińska's trial made the front pages of many French newspapers. The daily "L'Express Du Midi" also wrote about him in the issue of February 8, 1925.

"The dying believe in life as the galley slaves believe in freedom!" No one has the right to kill for either too much hate or too much love. Today the law must bow to love and compassion. But if she goes out free, let her not be followed by sacrilegious applause. Let her go away in concentration and silence, in captivity of conscience, cries Prosecutor Guigne.

Is euthanasia acceptable?

In fact, the accuser's speech is a great defensive speech. The real lawyers of the defendant, Rudenko and the dean of the Paris Bar, Henri Robert, fare much less in their concluding speeches.

Rudenko tells about the actress's life, then reads out a series of fragments from Żyznowski's last novel, in which, according to the defender, the writer predicted his tragic end. Moved, exasperated audience does not notice that the novel of the dead man is at least a weak argument in favor of Umińska's acquittal, which, of course, her defender firmly demands.

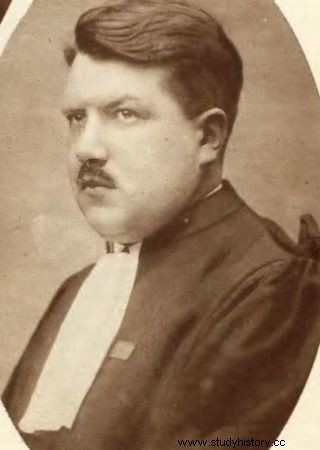

Defender of Umińska, Alexander Rudenko.

Henri Robert emphasizes that the accused from the first moments after meeting Żyznowski was influenced by his higher mind and talent. The lawyer asks the jury to recognize that the defendant acted under duress, because her beloved man Jan Żyznowski deprived her of power over his actions, making this delicate woman an excuse that she did not kill him faster. Then the defense attorney reads out a dispatch from the artists of Warsaw theaters asking for gentle treatment of the unfortunate friend. Finally, an ace up the sleeve.

Attorney Robert reads a letter from the shot to Stanisława Umińska, in which Mrs. Żyznowska forgives her and gives her blessing. Loud cries are heard in the room.

Five minutes of reflection

The accused's last word disappoints the audience that is expecting strong impressions. Umińska speaks little French, so she is helped by her translator, Mr. Smólski, sent by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The actress declares that she loved Żyznowski madly and was ready to give all her blood for him. That's all.

After the judge read the acquittal, everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

The judges come out to council. After five minutes they come back:

- Innocent!

The audience is like a kid, applauding and cheering. The ladies are crying again. This time for joy. Umińska in the arms of her friend leaves the room without a word.

Source:

The article is a slightly shortened version of the chapter "Cherub shoots ... with love" from the latest book by Włodzimierz Kalicki, entitled "It happened" (Znak 2014). Title and subtitles come from the editors.