In October 1962, tensions between the US and the USSR reached their zenith. Cuba became the arena of their political games. When the crisis was overcome, the world breathed a sigh of relief. How close was the outbreak of the nuclear war? Was it really only one step from nuclear annihilation?

In April 1961, the Americans backed the failed attempt to overthrow Cuban refugees by armed invasion of the Fidel Castro government in Cuba that was clearly shifting to communist positions. Khrushchev responded by provoking an even more dangerous crisis.

It had two main goals. One was to give the Castro government effective military safeguards against further American invasion attempts. The second goal was a short, sharp jump towards establishing temporary nuclear equality by installing in Cuba medium-range Soviet missiles that could threaten the center of America and thus counterbalance the ring of American bases that pose a threat to the Soviet Union (...).

Fatal error of judgment

In May 1962, Khrushchev agreed with Castro on the Operation Anadyr plan, in which the Russians would secretly deploy thirty-six R-12 medium-range ballistic missiles in Cuba and forty-two Iliusin Il-28 nuclear bombers, capable of directly threatening large cities in the United States. / P>

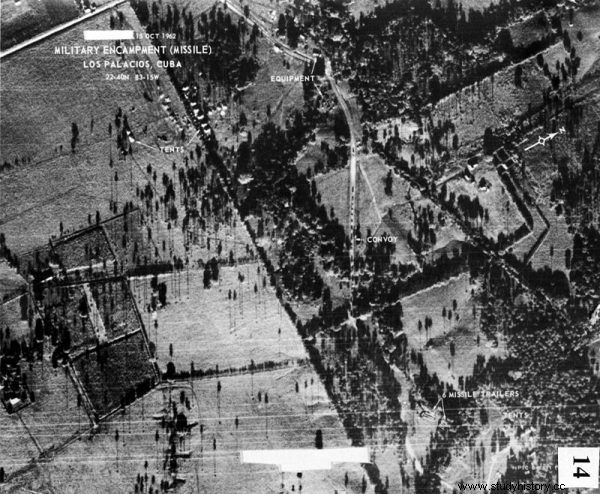

Photo of missile equipment in Cuba, taken from the deck of the U-2 on October 14, 1962.

The island itself would be defended by four mechanized infantry regiments, two regiments of a mobile missile system equipped with nuclear warheads mounted in missiles - the so-called FKR (acronym for the Russian name of Frontovaya Kryliatnaya Raketa), a dozen tactical Luna ballistic missiles with a range of approximately fifty kilometers, forty fighters and naval forces including submarines.

The success of the operation was to depend on flawless planning, precise execution, and a veil of a secret so tight that the Americans would not penetrate it until it was too late for them. These were tough conditions to meet, but if they worked, the game would be worth the candle. Khrushchev was informed that it was possible. And since he had no intention of starting a war, he assumed the Americans would come to terms with the fait accompli.

It was a fatally wrong judgment. The Americans had been wondering for some time whether the Russians could try to place missiles in Cuba. (...) On September 4, Kennedy publicly warned that "serious problems" would arise if he obtained evidence of Soviet military bases or missiles on the island.

By the end of September, the Americans had not yet determined the full extent of the deployment of Soviet forces. Thirty thousand Soviet soldiers under the command of General Issa Plijew have already arrived in Cuba. Their Luna combat missiles, if anything happened, could destroy the US base in Guantánamo. The missile regiments were on their way, and the submarine forces were about to leave the Soviet Union (...).

On October 15, however, the intelligence U-2 planes returned with photos from Cuba showing that missile positions were undoubtedly being prepared there. On October 18, the photos were on Kennedy's desk when the Soviet Foreign Minister visited him. Kennedy read him his September 4 statement. Gromyko was evasive. The Americans reacted furiously, convinced that he was lying to his eyes (…).

This text originally appeared in Rodrick Braithwaite's book, "Armageddon and Paranoia. Cold War - Nuclear Confrontation ” , which was released by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.

The world is armed to the teeth

The first Kennedy Executive Committee meeting on crisis management - the ExCom (Executive Committee) - took place four days later. The Chiefs of Staff believed that the missiles in Cuba would seriously affect the strategic balance. McNamara was of a different opinion:The Americans had about five thousand strategic warheads, while the Soviet Union only had three hundred.

An additional forty missiles in Cuba would make a little strategic difference. But Kennedy believed that the political balance would be upset. This was unacceptable. General LeMay presented a plan to bomb the island. Kennedy rejected him:he was awaiting the results of the negotiations.

(...) To strengthen his position, he agreed to alert the US nuclear forces and to make preparations for an attack on Cuba. (...) On October 22, he announced that all ships going to Cuba would be turned back if their loads contained offensive weapons. The possibility of a nuclear confrontation is now quite real.

In the third week of October the Soviet military were convinced that the outbreak of war was imminent . Plijew's rockets with nuclear warheads were mounted (…). Soviet forces in Poland were ordered to stop all maneuvers and return to their command posts and prepare for action (...).

Soviet submarine B-59 forced to surface on October 28 or 29, 1962.

Rockets at the cosmodrome in Plesieck were prepared to strike New York, Washington, Chicago and other American cities. Soviet strategic bombers were moved to their starting positions. Four Foxtrot submarines left Murmansk on October 1 (...).

Rassocho was to tell the captains that they were authorized to use their nuclear torpedoes under three conditions:if they were attacked by depth mines, their ships would be seriously damaged, if they were fired upon when surfacing, and if given specific orders from Moscow (...).

On October 24, in the midst of the crisis itself, the Americans informed Moscow that if they encountered a submarine, they would drop a harmless explosive grenade near it as a signal for him to surface. It is not clear whether this message reached the submarines, but American ships now harassed them not only with grenades that sounded like depth mines, but also giving the impression that they were going to ram them, and in one case even a torpedo launch was faked.

One by one, the submarines had to emerge with discharged batteries and broken engines. (...) After returning to Murmansk, the captains faced criticism for their submission to the coercion applied by the Americans. They should have used torpedoes or sank in their submarines.

On the brink of conflict

(...) The American side was also close to a catastrophe. The US Armed Forces had an alert system called DEFCON (Defense Readiness Condition), graded from 5 to 1. DEFCON 3 ordered the aviation to be alerted within fifteen minutes; DEFCON 2 was the last step before the nuclear war.

Kennedy Administration during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The alarm was to be announced by the president and the minister of defense through the Joint Chiefs of Staff. On October 22, the United States Armed Forces (with the exception of those in Europe) issued a DEFCON 3 alert. On October 24, General Thomas Power, chief of Strategic Aviation Command, raised the alert to DEFCON 2 without consulting the President.

To make sure the Russians noticed this, sent this order unencrypted to his bases around the world. Twenty-three B-52 bombers armed with nuclear bombs were directed to places within the firing range in the Soviet Union. Even the recalled B-47 Stratoyts were put on standby for fifteen minutes.

More than five hundred interceptors carrying nuclear weapons on board were deployed within one hour's flight from Cuba. Their pilots were authorized to use their weapons only on the orders of their superiors. But there were also no technical safeguards to prevent bombs from being dropped on their own initiative (…).

There were no effective technical safeguards on both sides to deter soldiers, sailors and airmen. Washington and Moscow had to rely on the discipline of their commanders and their soldiers.

War canceled?

Eventually, Khrushchev agreed to withdraw his missiles and troops from Cuba. Kennedy promised in return that the Americans would not invade Cuba and privately that they would withdraw their Thor and Jupiter rockets from Turkey. Khrushchev played with bravado and dangerously. A British observer of these events later commented that "he achieved what he set out to do, although not necessarily as intended."

This text originally appeared in Rodrick Braithwaite's book, "Armageddon and Paranoia. Cold War - Nuclear Confrontation ” , which was released by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.

Not all of them were so kind to him in terms of their judgments. Khrushchev's colleagues cited the defeat in Cuba as an argument when they forced him to resign two years later. Also, not everyone on the American side was satisfied. Curtis LeMay never renounced his belief that the Americans should have invaded Cuba and destroyed the Soviet missiles there (…).The American and Soviet governments managed to scare both themselves and the enemy to death. Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador to Washington, later wrote:"I must emphasize the enormous importance of the Cuban crisis for the subsequent course of Soviet-American relations."

(...) Deputy Foreign Minister Vasily Kuznetsov told a senior American official:"This time you have succeeded, but you will never succeed again." Cuba's lesson was forgotten when the Russians began the massive build-up of their nuclear forces, and the Americans responded with the same. The arms race has accelerated and become even more dangerous.

Source:

The above text is an excerpt from Rodric Braithwaite's book " Armageddon and Paranoia. Cold War - Nuclear Confrontation ” , published by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.

The title, lead, illustrations with captions, bolds and subtitles come from the editorial office. The text has undergone some basic editing to introduce more frequent paragraph breaks.

A shocking story about the times of paranoid fear of nuclear catastrophe in the book " Armageddon and Paranoia":