A three-day rest was announced. At that time, we were waiting for a change of escorts. The Soviets who led us this far did not have the appropriate equipment and could not lead us further into the forests. Winter in this area was almost ten months and the snow rarely disappeared.

Therefore, guards with exceptional resistance to such conditions were needed. They recruited from "Mongolian barbarians" living and working in an arctic climate who were known for their cruelty and violence.

Death March

We slept in huge, empty rooms, huddled together for warmth and company. Three nights of relative comfort and two meals a day helped us regain some of the lost strength. On the fourth day, when the Mongols arrived and began vigorously preparing for the journey, all hell broke loose. We had scarcely finished our soup and they had already rushed into the room and had us form ranks. We were chained around fifty or so and lined up in six marching columns. Unlike the Soviets, the Mongols were proud to command so many related prisoners.

As we passed through the city center, they kicked and beat us, pleased with the sensation they were making. Even though they had sleigh and horses at their disposal, they preferred to go with us. Dressed in fur, they looked impressive with convicts in thin coats and worn boots. They didn't seem to be convincing, and it did indeed prove as they traveled.

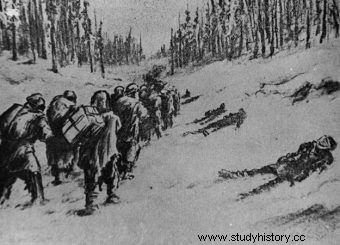

Many exiles were unable to survive the murderous marches

The first day was relatively quick because the snow was packed and it was easy to walk on. In addition, we were all refreshed after a short rest, so without much effort, after about thirty-two kilometers, we reached the barracks for the first rest. Nutrition returned to the previous "standards":herring, a portion of bread and hot water once a day so after the steaming soup in Krasnowiszersk it was disgusting. We asked to release our chains for the night, because without them it would be more comfortable to sleep. In response to this request, we received a series of painful kicks for causing problems and were ordered to remain silent.

In the morning, the Mongols burst into our room and, before we had time to collect our thoughts, they began to pull us by the legs and drive us away to the overwhelming frost. Conditions worsened considerably. As we left the beaten track into the forest, the snow was getting deeper. It was difficult to keep your balance and the columns kept stopping because some of them fell over and stuck in the snow. Angry guards tried to put the hapless prisoners on their feet, hurling insults at them. Suddenly one of the Ukrainians fell. His companions helped him to his feet, and for some time, leaning on them, he kept himself straight. But they also didn't have much strength, and they didn't have enough strength to support him any longer. His legs buckled under him and he fell to the ground, unable to make the slightest movement.

Someone has to feed the wolves

The enraged escorts tortured him for a long time, but the prisoner was completely exhausted. One of them unfastened the chain and two others picked up the man. We turned and watched as they dragged him half-dead toward the sled. We thought that maybe she would continue her journey there, but it did not. Soon the guards returned laughing and joking, but the prisoner was nowhere to be seen. On the second day, six people disappeared this way. I was curious about their fate, so finally I summoned my courage and asked one of the Mongols what happened to the bodies of the others.

"We just need their clothes to prove they were here," he replied. "And the wolves must be fed, or they will attack the convoy and you will all die." We must reach the barracks before dark. Take a good look and you will see wolf tracks. They are always close, day and night follow us. They know there will be enough food to eat. If I were you, I wouldn't ask questions. It's a waste of energy, you'll end up like them.

Polish exiles

In three days we had traveled more than one hundred and forty kilometers, almost half the way, but we lost about thirty comrades who were stripped after death, their bodies left in deep snow to the prey of the wolves that approached them as soon as we were out of sight. / P>

Survive the night

We were also plagued by frostbite at this stage. Many were on the verge of death. There would have been many more victims if we had luckily not reached a small settlement on the shores of a frozen lake. To our general amazement, our chains were removed. The convoys were terrified by the death toll. They were ordered to bring a whole group of prisoners safely to their destination in good condition and ready to start work immediately. Meanwhile, thirty had already lost their lives, and the remaining two hundred and seventy were completely unfit for work.

Our meals have changed again. We were served more digestible groats and hot water, and the food rations, compared to those given in the previous barracks, were decent. After the meal, we lay down on the floor for a well-deserved sleep. I have noticed my hands and feet are swollen, almost numb. I massaged them to restore circulation. I curled up into a ball and wrapped my cloak around my feet, trying to make a warm cocoon out of it. I fell into a shallow sleep because a piercing chill engulfed my whole body and chilled my soul. Perhaps it saved me. I felt that if I fell asleep deeply, I wouldn't wake up anymore.

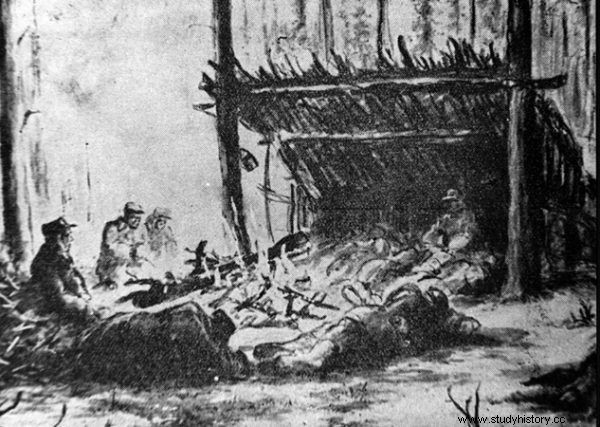

The first phase of the construction of the camp in the taiga, until the barracks were erected, the prisoners slept in huts made of branches.

. Drawing of an unknown labor camp published in the publishing houses of the II Corps.

Suddenly, the Mongols, more aggressive than usual, started to wake us up with kicks and punches. We were going to be the audience for the official guest with lots of medals pinned to his thick fur. I couldn't understand what he meant. He seemed to be discussing the great achievements of Soviet communism and praising Stalin's virtues as the father of all workers. He argued that we were one of the privileged few who had been allowed to help him ensure better communication throughout his beloved country. Looking at us contemptuously and with his hands clasped behind his back, he paraded back and forth in front of us. At one point, a Russian prisoner broke through, who probably could no longer bear the humiliation.

Stalin's "children"?

- If Stalin is so great, let him come here and convince himself of his remarkable successes. There are three hundred of us - his so-called children - hungry, emaciated and numb from the cold, with swollen arms and legs, many close to death. Nevertheless, we are rushed through this frozen wasteland, forced to sleep on a concrete floor in makeshift barracks and fed with overcooked groats. These are Stalin's beloved children? So far, my friend, thirty of our companions have died. Did Stalin feel this loss? Does he know that his thirty children were left in the forest without their clothes abandoned by the wolves to be eaten? Of course not! The death of a human means nothing to you. For you, we are just animals, workhorses, which are to serve you in your advancement in the development of communism.

Four guards appeared in the room. After a brutal struggle, they pulled out a prisoner who was still insulting the Soviet proletariat and Stalin's rule. He did not return anymore, but gave spirit to his companions who, with some effort, applauded in appreciation of his courage. For them, he became the hero who paid for her with his life.

It had been snowing heavily outside for some time. The snowstorm lasted all day and voices were heard that the snow layer was well over a meter. There was a conference of Mongolian guards with Soviet officials who thought it unwise to risk the lives of horses because it was difficult to find new ones in the far North. As always, the Mongols were hyperactive, and they wanted to hit the road. It was decided to give the convoy one more day of rest, but two days passed and we were still in the same place. We prayed for more snow, the deeper it was, the better, because each day of delay was an extra time of rest for us.

The article is an excerpt from Michał Krupa's book "Shallow graves in Siberia", which has just been released by the Rebis publishing house.