Bolesław the Brave conquered many lands, but the capital city of Gniezno was not threatened until 1003, when he took control of Praga. The Czech capital was a city from a completely different league. There is a view that the Polish ruler wanted to move his capital to the Vltava River. Or maybe even ... he did.

Gniezno and other great forts that arose in the 10th century in the area of today's Wielkopolska were off the beaten track of trade routes. Yes, they were impressive, they made an impression, but hardly anyone looked at them. This is one of the reasons why the Piasts who ruled them appeared in the sources relatively late, around 965.

Meanwhile, Prague was a real metropolis. It lay on an important trade route that ran through Regensburg, Lyon and Provencal ports to Arab Spain on the one hand, and through Kyiv to the markets of the Orient on the other. Every day merchants of various nations came there, exchanging silver, pearls and silk for furs, wax, honey, amber, and above all slaves . Prague was a real center of human trade .

Ibrahim ibn Jacob, a Jewish merchant from Muslim Spain, wrote that the city was "made of stone and lime." Although there were plenty of wooden houses in the Czech capital, if you could call any of the castles in this part of Europe "a pile of stones", it was Prague. And it wouldn't be an insult at all, but a commentary on the impressive architecture!

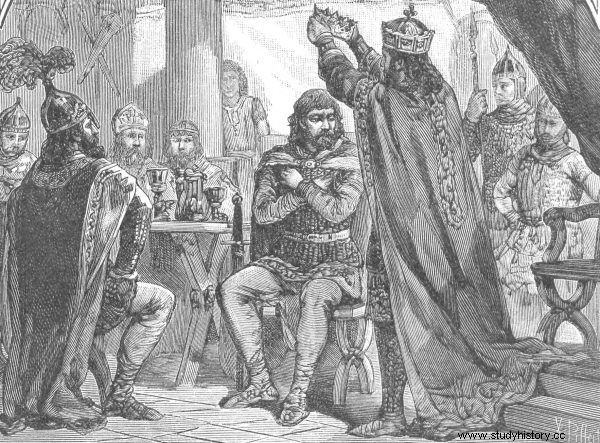

It was in Gniezno that Brave met the emperor in 1000. But a few years later, the position of this city as the capital was put into question. A fragment of an illustration by Ksawery Pillati from the book "Images of Polish kings and princes" from 1888.

Bolesław Chrobry knew a lot about the capital of our southern neighbors. He probably remembered a bit from the stories of his mother, the Czech princess Dobrawa, the rest was added to him by diplomats and a few merchants, who strayed from the main routes and touched on Gniezno. During the reign of his father Mieszko I, he could visit Prague. The sons of the chiefs were often sent on diplomatic missions, and Chrobry was fit for talks with the Czechs like no other, because he was the nephew of Prince Bolesław II, who ruled over the Vltava.

Considerations as to whether Prague would be a better capital than Gniezno were theoretical deliberations for a long time - until the year 1003, when Bolesław the Brave took the Czech Republic. This conquest was not spiced with great military actions and victories. As befits a racial politician, the Polish ruler took advantage of the battles fought between Czech princes and magnates. He was not a passive observer, because whenever he could, he cleverly incited one against the other. Thanks to this, in March 1003 he appeared with his team at the gates of Prague. He did not have to conquer the city; The Czechs welcomed him with joy and hope that he will put an end to internal struggles. So Bolesław sat on a stone throne that belonged to the Czech princes.

And at that moment the question arose:would it not be better to reside in Prague, which is so wealthy, vast and well-connected, instead of sitting in the outskirts of Gniezno? In other words, isn't it time to change the capital?

Wait, there were capitals in the 11th century?

Someone might object that there were no "real capitals" in the Middle Ages. After all, the monarch spent most of his time traveling around the country. It was a real nuisance for the inhabitants, who hastily hid their belongings, especially animals, so that they would not be robbed by the princely surroundings. Bolesław also traveled, although - if we believe the idealized description of Anonymus called Gall - no one "hid oxen or sheep during his marches, but the man who passed by was joyfully welcomed by the poor and the rich, and the whole country was in a hurry to see him".

Even so, there were "real capitals" in the Middle Ages. As the famous medievalist Jacek Banaszkiewicz points out:

this is where, at home, medieval dynaists were at home and there, as the Slavic names attest, he sat, sat on majesty (table-stool-capital; ks When translating the Bible at the end of the 16th century, Uncle translates the word throne with the phrase 'court capital'.

Chrobry's complaints about Praga were motivated by the Czech origin of his mother. Dobrawa's drawing made by Edward Knapczyk based on the portrait of Jan Matejko.

The capital of Rus on the Danube, and also of Poland on the Vltava

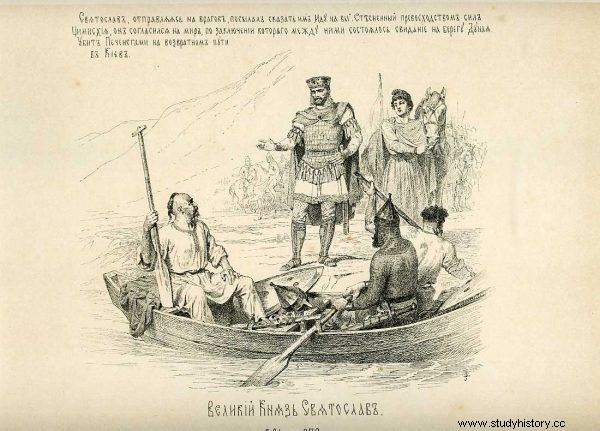

The Slovak historian Ján Steinhübel has no doubts that the Polish leader saw the seat of his great monarchy on the Vltava and in 1003 he wanted to move the capital from Gniezno to Prague. He points to an interesting analogy with the Ruthenian prince Svyatoslav, who in 969 conquered Bulgaria and made Preslav on the Danube his capital instead of Kiev. Although the Russian ruler died three years later, and Kyiv regained the palm of precedence in the country, the very mechanism of changing the capital city is important here.

It is worth taking up this trail and asking if Bolesław realized his intention. Prague was not only an important trading center. At the same time, it even had a "capital city tradition" that was longer than Gniezno. Before Bolesław it was ruled by sixteen rulers of the Přemyslid dynasty, in Gniezno of Disease he was at best the fifth ruler of the Piast dynasty. Archaeologists even believe that the Piasts initially resided in another city - Giecz or Kalisz. It would be difficult to find a justification for permanently residing in Wielkopolska and not poking your nose out of it.

The Grand Duke of Kiev Svyatoslav also moved the capital far away from the center of the state. In this 1896 drawing by Vasily Petrovich Vereshchagin, we see him on the banks of the Danube.

Bolesław Chrobry was present in Prague in March 1003, when he inaugurated his rule, and in June 1004. Reading the chronicle of Thietmar, the only source that accurately describes the actions of the Piast during this period, one can get the impression that all this time the Polish ruler's command center was located on the Vltava. Prague itself became the most important castle in the enlarged Poland.

If it was de facto the capital of the great monarchy of Bolesław the Brave, this state lasted only a dozen or so months. In June 1004, the army of the German king Henry II, accompanied by Prince Jaromir of the Czech Přemyslid dynasty, Bolesław's cousin and pretender to the Czech throne, entered the Czech Republic. Chrobry did not allow himself to be circled in Prague, but literally at the last moment he evacuated with his team - probably to Moravia.

Chrobry in Prague

The story with Prague as the supposed capital of Poland at the beginning of the 11th century is a good starting point to reflect on how strange the winds of history are blowing. After all, the scenario in which Chrobry keeps the Czech Republic in its hands for longer was quite likely, since the Piasts had previously managed to take over Kraków or Moravia. And then, who knows, if millions of tourists visiting Hradcany would not stop at the basilica of Saint George ... at the tomb of the first king of Poland, the greatest conqueror the Piast family released.

Studies:

- Adamczyk Dariusz, Between Kiev and Gniezno. Selected aspects of the topography and function of Arab silver in Poland in the 10th and early 11th centuries , "Polish and Universal Medieval Times", 1 (5), 2009.

- Banaszkiewicz Jacek, O king, this and that - non-historic , [in:] Kings and bishops in the Middle Ages , edited by Michał Brzostowicz, Maciej Przybył, Jacek Wrzesiński, Poznań - Ląd 2012.

- Matla-Kozłowska Marzena, The first Przemyślids and their country (from the 10th to the mid-11th century). Territorial expansion and its political conditions , Poznań 2008.

- Pleszczyński Andrzej, "Amicitia" and the Polish case. Comments on the Piasts' attitude to the Empire in the 10th and early 11th centuries , [w:] Ad fontes. On the nature of the historical source , ed. Stanisław Rosik, Przemysław Wiszewski, Wrocław 2004 ("Acta Universitatis Wratislaviensis" 2675, "Historia" 160).

- Pleszczyński Andrzej, Bolesław the Brave in the Czech Republic. The implementation of the idea of Sklavinia or a simple expansion? , [in:] Poles in the Czech Republic. Czechs in Poland in the 10th – 18th centuries , ed. Henryk Gmiterek, Wojciech Iwańczak, Lublin 2004.

- Steinhübel Ján, Capitols of the oldest český dejín, 531-1004 , Krakow 2011.