I want you to take your time and think about what was the product that sold out at the beginning of the pandemic and that is still available everywhere. To help:I don't mean only in spaces, but also in your pocket or bag. The one for which bodies 'fell' in supermarkets, which allows us to touch everything without stress and possibly keeps Covid-19 under control (we say now) even more than the mask.

Today we will talk about the man who gave the planet the antiseptic. Or if you prefer hand sanitizer. First let's mention some numbers. According to CNBC, sales in the UK alone increased in February by 255% (each person had two) and in Italy by 1,087%. Worldwide revenue reached $11,000,000,000 in revenue.

Our own Thanos", a NEWS247 documentary about the great Thanos Mikroutsikos, through the eyes and soul of 20 of his own people. Songwriters, directors, writers, politicians, musicians, describe, remember , they paint with words and soul, the portrait of Thanos. It comes on Monday 12/28 on NEWS247.

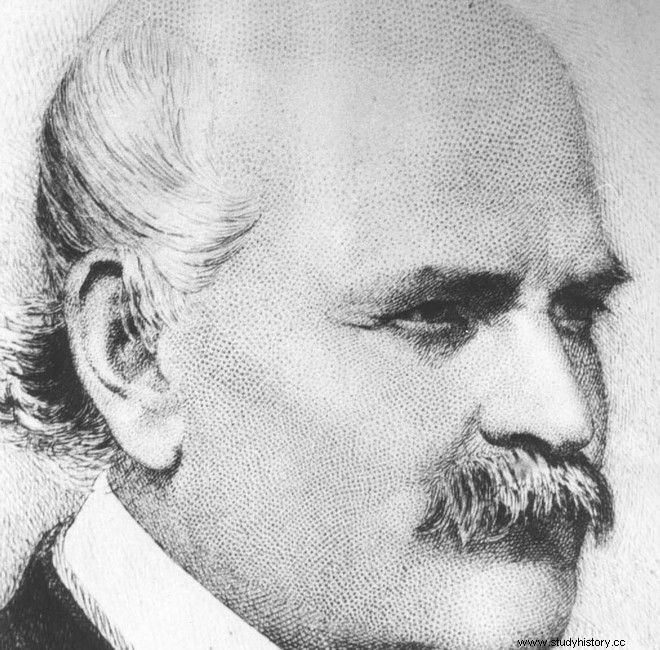

The 'mantra' of the pandemic was the phrase that Ignaz Semmelweis kept repeating in 1850, trying to convince that this simple thing was enough to save lives. The Hungarian obstetrician (he noted that obstetrics had been established as a recognized medical specialty since the early 19th century) had accepted an invitation to speak at the Gesellschaft der Ärzte - the College of Physicians in Vienna that exists to this day. From the beginning (1802) it was a place of 'fermentations', education and presentation of all the new ones arising on infectious or other diseases that afflicted the world. For example, there Karl Eduard Hammerschmidt demonstrated the first pulsometer in history, in 1843.

On 5/15/1850 those present did not know what Semmelweis had discovered and could save lives. He summed it up in four words:'wash your hands'.

Now that you are reading this, you will take it for granted that all doctors meticulously clean their hands before any examination or operation. That wasn't exactly the reality then. Microorganisms (microbes - fungi, helminths, protozoa, bacteria and viruses) did not exist as a concept. I mean they hadn't been 'discovered' yet. Their existence was ignored - even though they were everywhere. Also, there was no 'gynecologist' specialty. It emerged in the 1880s and in 1889 the relevant department was created at John Hopkins Hospital.

As PBS has written, by the mid-19th century, five out of every 1,000 women died in childbirth performed by midwives in hospitals or homes. In the births performed by the doctors in the best hospitals of Europe and America the deaths were 10 to 20 times higher. They were found to be due to infection, leading to sepsis and eventually death (all within 24 hours of birth) without being able to explain further. Because there was ignorance, autopsies were performed the day after the deaths. The doctors who performed them were also the ones who examined the expectant mothers, every day.

They did it all with their bare hands, and in the best of cases, it involved hand washing with soap.

Our man, who worked at the Vienna General Hospital, was Hungarian and Jewish, a combination that kept him away from the specialties for which Vienna was famous. That is, medicine and surgery. He had been assigned to deal with what others did not want. It was obstetrics. His job was to examine the patients every morning before the doctor went to see them, supervise difficult births and teach the students the job. He was also assigned to keep minutes.

Fact:maternity hospitals were created to deal with the problem of infanticide of 'illegitimate' children. They provided free services and care to infants. Unprivileged women - including prostitutes - resorted to them. In return, they made their bodies available for the training of doctors and midwives. The Vienna General Hospital had two maternity wards

As Semmelweis kept the records, he found that 1/3 of the newborns had died from the same reason. He decided to investigate who exactly he was - where it all started and how it developed. He also noted that he had received dozens of pleas from expectant mothers who begged him to discharge them, as they believed that doctors were harbingers of death - the mothers of the time had (let's say) made the phrase 'plague of doctors' viral.

In 1947 his friend Jakob Kolletschka died. In the autopsy they found that she showed the same pathology as women who die after giving birth. Kolletschka had been 'stung' by his student's scalpel while they were performing an autopsy. Semmelweis suggested that the connection between contamination of the corpse and puerperal fever be considered. He had the means ready.

He and the students he supervised would transfer the 'necromorphic particles' (today it is the bacterium called group A haemolytic streptococcus - but then the germs did not even 'exist' as scientifically proven) from the autopsy room to the pregnant women being examined in the ward of the first maternity clinic. The second would be undertaken only by midwives who had nothing to do with autopsies - and contact with corpses. The result was what he expected. Deaths in the midwifery clinic were fewer.

Historians make it clear that Semmelweis was not the first to connect the dots. Others had come before. The last was Oliver Wendell Holmes, an anatomist at Harvard, who had recommended in 1843 that obstetricians not participate in the autopsies of women who had died of puerperal fever. It didn't help that back then there was no Internet -or even a phone.

So in Austria, in 1847 Semmelweis had ordered his subordinates to wash their hands with a solution he had created that contained chlorine and lemon juice "until the smell of the infected tissues of the corpses disappeared", between autopsies and exams. Then he tried to get everyone to retire. Many (the higher-ups) felt that he insulted them (that he was calling them dirty - besides being responsible for the deaths of the pregnant women) and stubbornly refused to listen to him.

In the first six months of using the solution to clean the -bare- hands, deaths from puerperal fever dropped by 90%. Hand washing as recommended by the expert became mandatory in the month of April. Deaths dropped from 18.3%, to 2.2% three months later and 1.9% four months later.

He began sending letters to all the other hospitals, informing them of the results and largely demanding that they follow suit. There were many who questioned him. The more they became, the more his irritation increased - he felt that his right was "suffocating" him. His behavior was becoming extreme. Of the level of sending letters to hospitals that rejected his findings, in which he characterized the most powerful academics as 'irresponsible murderers'.

In 1850 he lost his license and left the Vienna General Hospital. He left for his homeland, without even informing his closest associates.

For years he would not listen to those who suggested that he publish what he had found, no matter how much they begged him. He did it 13 years late (1861) and after he had become persona non grata. The title he gave to the explanation of his theories was “Die Aetiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers” ('the etiology, rationale and prevention of puerperal fever').

From early 1861 his behavior became increasingly erratic. He suffered from depression and had become withdrawn. In addition, every conversation he had "brought" to the topic that concerned him. By mid-1865 he had annoyed everyone with his behavior. He had also started drinking alcohol, spent more time with prostitutes than with his family, and generally had a complete change in character and behavior. On 7/30 of that year a doctor invited him to see one of the new clinics in Vienna. He took him to a psychiatric clinic. He tried to escape when he realized what the truth was. He did not make it. He died two weeks ago. He was 47 years old.

Some historians point out that during an operation, he contracted syphilis, which explained his paranoia. Others that he got a blood infection and then sepsis, while he had bipolar. The latest research says he had Alzheimer's and was beaten to death by asylum guards. They caused him the gastrointestinal wound that was the cause of his death. The autopsy also showed blood poisoning. Everyone agrees that the medical community was not ready to accept what he had discovered.

It was justified when Louis Pasteur discovered germs, in the late 1850s. You have been informed about this, in the history of the vaccine.

The first doctor to use an antiseptic in an operation was Joseph Lister, a Scottish surgeon at the Royal Infirmary in Glasgow. He had read Semmelweis' report and Pasteur's article on germ theory. He realized that the former's solution 'killed' the germs that were causing the infection. He began wrapping the wounds with a bandage soaked in carbolic acid (a phenol - with bactericidal, antiseptic and antiparasitic properties) and discovered that the mortality after treatment from infections was reduced, while the incidence of sepsis was reduced.

He suspected the actions of phenol as an adequate disinfectant, from its use in fields irrigated with waste, to alleviate the smell. He assumed it was safe as a material, since the same fields treated with carbolic acid had no apparent adverse effects on the animals that grazed them. Lister became the 'father of modern surgery'.

The 'Listerine' you know was the work of Dr. Joseph Lawrence, who gave his discovery (the mouthwash) the name of the scientist who paved the way for sterilization.

As the Industrial Revolution reports, antiseptics made surgery a viable treatment method. Before they were discovered, surgeons operated only if there was no other possible treatment - since operations led to infections and death.