“The lay people in Iceland who owned the manuscripts sat on them like dragons on gold. »

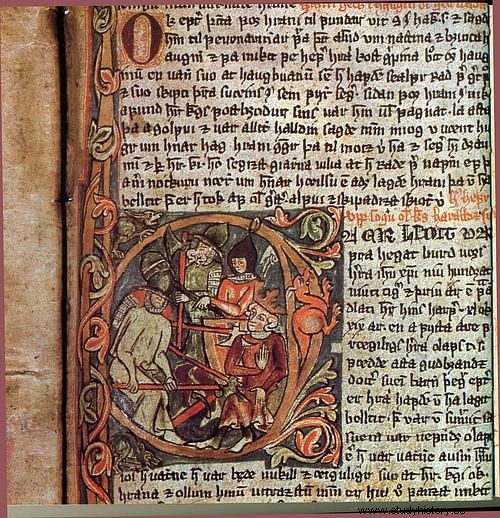

This is the bitter observation presented by the Reverend Magnús Ólafsson in the seventeenth century in a correspondence with the Danish scholar Ole Worm. But what is this treasure that has reached us with so much difficulty? Manuscripts, fragments, literary texts and in particular the famous Icelandic Sagas. Before presenting the one who has worked so hard for its conservation, let's first define what a "saga" is. (1)

If we take the definition of the specialist in Scandinavian civilization Régis Boyer, here is his definition:

A prose story, always in prose, relating the deeds and gestures of a person worthy of memory for various reasons from his birth until his death, omitting neither his ancestors nor his descendants if they are of any importance. They are of unequal lengths. A saga is not a legend or a tale, nor a poetic, period or religious text. It is similar to a historical novel as it flourished in the Romantic era. If they take true facts and/or customs, these texts cannot pass for true historical documents

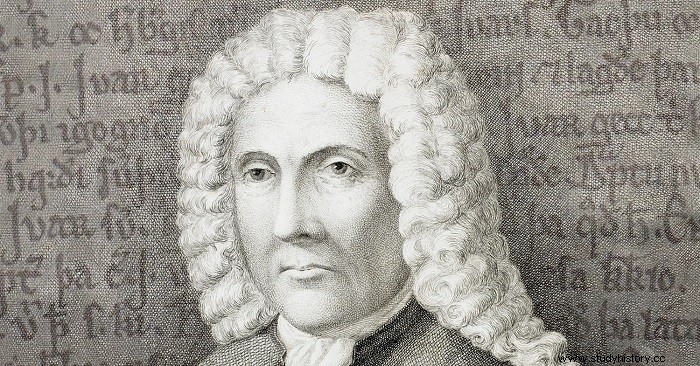

Árni Magnusson was a manuscript hunter in Iceland. He was looking for manuscripts on vellum before. Its mission, in the 17th and 18th centuries, followed in the footsteps of scholars from all over Europe who were busy finding manuscripts at the beginning of the Enlightenment. Historical research was dressed as a rational disciple, free from political interests and religious prejudices.

Born on November 13, 1663, he went to Copenhagen at an early age to study at university and later become secretary to the new royal antiquary, Thomas Bartholin. At the age of 38, he was appointed professor of history at the University of Copenhagen. The child of the country of the giants will return there for a period of ten years as a member of a royal commission responsible for drawing up a register of all the farms in the country. This is both a census of people and livestock and a check on whether law and order were being enforced.

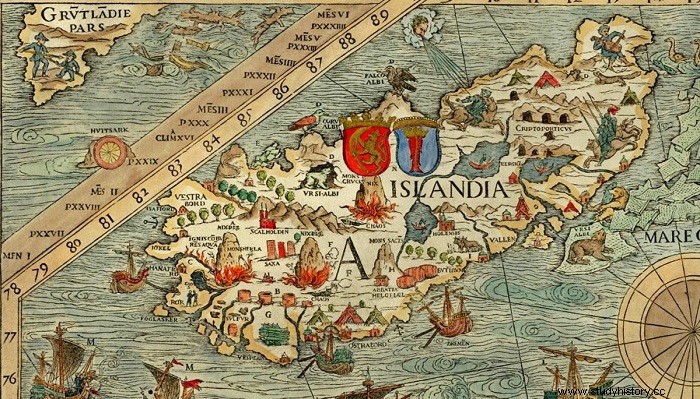

On a European scale, Iceland is a town. A poor country with 50,000 inhabitants.

Arni Magnusson's life has been a long journey of collecting manuscripts. With some 2,500 pieces, it is the oldest collection dating from the beginning of the 12th century. The vellum manuscripts represent about one-fifth of the lot. Note, however, that a major part of the collection consists of post-medieval manuscripts that he obtained and/or paid scribes to write. Manuscripts containing texts of the famous Icelandic family sagas number about two hundred in his collection.

In Iceland, scholars from Denmark and Sweden began to study medieval Icelandic texts with the help of Icelandic students and travelers. Most of them belonged as family treasures to wealthy families. Reverend Magnús Ólafsson said in 1632 that the laity in Iceland possessing the manuscripts "sat on them like dragons on gold". The first collector who succeeded in collating them was Brynjólfur Sveinsson, who became Bishop of Skálholt in 1639. In 1656, Bishop Brynjólfur sent extremely important manuscripts to King Frederik III of Denmark, hoping that he would have the texts in Latin. Among these manuscripts was the famous Flateyjarbók, containing sagas of Norwegian kings, written in 1387-1394. In 1662, the king sent the Icelandic scholar Þormóður Torfason to Iceland to collect manuscripts and Bishop Brynjólfur, again.

The dissemination of these medieval texts were later disseminated to the educated upper class and to some wealthy farmers. Later, Latin translations were published in Sweden and Denmark in the 1660s and in Iceland in 1688.

Thomas Bartholin engaged him as his assistant in the summer of 1684. The following months were spent sifting through manuscripts of uneven quality, and Árni took hundreds of extracts from Icelandic family sagas and Norwegian and Danish king sagas. From the beginning, therefore, Árni had a detailed and extensive knowledge of medieval Icelandic literature. His method of transcription was traditional, that is to say not very exact. He wrote using his own spelling and copied from all available manuscripts, most of them fairly recent and of varying quality. Thomas Bartholin knew very little about medieval Icelandic literature.

That same year, Jón Eggertsson brought many valuable Icelandic manuscripts to Sweden. The rivalry between Swedes and Danes was great during these years, resulting in intermittent wars, and both sides claimed older and more glorious origins than the other and used Icelandic texts to support their claims.

Bartholin was quick to suggest that there should be a Danish monopoly on the collection of manuscripts in Iceland and wrote to the king on April 4, 1685 that "as it is known that our neighbors have obtained from Iceland a large number of fine manuscripts which they publish in print thus causing us the greatest harm, I very humbly beg Your Royal Majesty to order your treasurer in Iceland, Christofer Heidemann, that he not only ban and ensure that no history or written document is sold outside the country to foreigners, but also that he collects all the manuscripts he can get and sends them to Copenhagen. » (2)

Arni Magnusson was thus sent to Iceland against a background of rivalry between the two countries. Árni and Heidemann, traveled to Iceland in the spring of 1685 with the explicit purpose of collecting manuscripts. Arni returned to Copenhagen a year later but brought little interest to Bartholin, who was clearly disappointed. Too idle to travel, Árni could not cover Iceland from top to bottom and he was too young to have the necessary connections. However, for his own library he obtained from his family and friends three venerable fourteenth-century manuscripts of the Jónsbók book of laws of 1281. This was his first serious contact with vellum manuscripts, and judging by the progress of his working methods over the following years.

In May 1694, the assembly of professors of the University of Copenhagen decided to send him for a period of two and a half years to Germany, to the town of Stettin in Pommern (today in Poland). The trip must have been a relief for Árni, who barely had enough money to support himself in Copenhagen. In August, he deposited his gaiters in Leipzig, a center of learning for the time and the largest book fair.

Among the manuscripts at his disposal, he was mainly interested in chronicles and other medieval historical works on the one hand and in the lives of saints on the other. He even enjoyed reading chronicles of events prior to the birth of Christ and noted that one of the manuscripts was beautifully written.

Árni himself wanted to own books for his personal collection and he bought hundreds of them, mainly recent books available in bookstores. But not everything could be bought and Árni did not have much money. In the library of the University of Leipzig, he read or at least leafed through thousands of books, made lists of titles and took a few notes – on rare occasions adding his own comments.

Intrigued by books on Pope Joan, he was particularly interested in historical works, Italian humanists attracted his attention. What fascinated Árni about the really old books was the fact that many of them were the first printed editions of old and important historical works concerning the medieval history of Europe. He compared the first editions with the more recent editions and tried to verify their accuracy.

Árni left Leipzig in September 1696 and would have liked to travel through Holland and England but had no money, and his protectors were apparently not as interested in extending his journey as he was. Back in Copenhagen, Arni began working at the Royal Archives. He hardly ever used any of the knowledge he had acquired in Leipzig.

Most of the vellum manuscripts had already been taken out of the country, but Árni knew that there were still many ancient manuscripts in fragmentary state. He was able to put several together, patiently and gradually putting together the pieces from different people and from different parts of the country. Not a scrap of vellum or old paper was overlooked. In addition, he annotated them, indicated the place of his find and gave some reflections on the value of the text. If he could not buy manuscripts and documents or obtain them as gifts, he hired good scribes to copy them with the utmost precision and vigilance, for example thousands of original documents too important for their owners part with it.

After Árni moved back to Copenhagen, he bought manuscripts at auction, and on the death of Þormóður Torfason in 1719 he acquired his collection of manuscripts. From time to time he received packets from Iceland, for example one with thirty-three sheets of vellum from his nephew Snorri Jónsson in 1721. The collection continued to grow and Árni harbored the hope that he would manage to make a catalog before his death, which did not happen.

His life's work of collecting manuscripts might also have come to naught. On the evening of October 20, 1728, a fire broke out in Copenhagen. It raged for three days, destroying at least a third of the city. Árni waited too long and did not order his belongings removed from his Kannikestræde home until it was almost too late. Only a few dozen manuscripts were destroyed, but almost all of his printed books, those purchased in Leipzig and later, and many of his scholarly notes and papers were lost in the fire. The same fire destroyed the university library, of which he was the guardian, with many valuable Icelandic, Norwegian and Danish manuscripts on vellum.

Árni died fourteen months later, on January 7, 1730, having bequeathed his collection to the University of Copenhagen the day before.

Notes

1. The collector Árni Magnusson did not specifically find the Sagas on his own, he is part of a movement specific to his time, let's take it for granted.

2. Denmark is in cultural decline if we are to believe Robert Molesworth, a politician of his time and Member of Parliament for County Dublin:“Denmark once produced very learned men, such as the famous mathematician Tycho Brahe, Erasmus Bartholin for physics and anatomy, Borichius, who died lately […] But at present, learning is at a very low level. There is only one university, which is in Copenhagen, and that means enough in every way; neither the building nor the revenue being comparable to that of the worst of our colleges. »

Find out more

A Collector of Early Modern Medieval Manuscripts, by Már Jonsson, Professor at the University of Iceland.

Medieval Iceland, Régis Boyer.

Icelandic legendary sagas. Texts translated and presented by Régis Boyer and Jean Renaud

B&W illustrations:Atlas of the trip to Iceland, by Gauthier de Lapeyronie:https://c.bnf.fr/ILd (BNF/Gallica)