The conquest of Wales was an old dream of the English kings, but the orographic difficulties and the guerrilla warfare strategy followed by the Welsh, who systematically avoided open field battles, made the conquest difficult.

One of these invasions was carried out by Henry III in 1257 and it was a complete failure. The Welsh, led by Llywelyn of Gwynedd, not only repelled the English attack, but in the following years took advantage of Henry III's internal difficulties to conquer various borderlands and increase the territory in his power.

In 1267, Henry's internal problems in his kingdom were joined by the decision of his son Edward to go on the crusades. To deal with both issues, Henry needed peace in troubled Wales. For this reason, he signed the Treaty of Montgomery (1267) with Llywelyn, in which he not only guaranteed the maintenance of the conquests of the Gwynned, but also, for the first time in history, England officially recognized a Welshman with the title of "prince". of Wales." In return, Llywelyn recognized the King of England as a superior lord to whom he should pay homage and promised to pay an important financial sum in the following years.

However, various issues made it difficult to maintain the Treaty of Montgomery later:firstly, this agreement had left unresolved border disputes between Llywelyn and various powerful English nobles, causing more than one clash between them; secondly, Wales was not a rich country, so the payment of financial compensation to which Llywelyn had agreed began to be delayed; Finally, the Prince of Wales was forced to face an internal rebellion led by his brother Dafydd, which ended with the rebels taking refuge on English soil to the anger of Llywelyn. The English magistrates limited themselves to pointing out that the Montgomery treaty prohibited England from supplying arms to the prince's enemies in Wales, but said nothing about receiving these enemies in England and that, therefore, they were not obliged to deliver these fugitives to Llywelyn .

When Edward I came to the throne, his initial attitude towards the Welsh problem was one of tolerance and understanding towards Llywelyn; in a more than difficult economic situation, his priority was to collect the compensation agreed in Montgomery, so he instructed his nobles and authorities to avoid any dispute that could serve as an excuse for the Welsh not to make payments.

However, Eduardo's patience was running out little by little. Several planned meetings between the two leaders (among other purposes, with the aim of having the Prince of Wales pay homage to the King of England) were frustrated, the last of them after Eduardo waited in vain for Llywelyn in Chester for a week and that the Welshman claimed that his safety was not guaranteed on English soil, which Eduardo interpreted as an insult to his offer of hospitality. In addition, he understood, and he was right, that behind it was a challenge from the prince to his position of vassalage with respect to the English king.

But the event that marked the final break between the two was Llywelyn's decision (single and childless in his fifties) to marry. This issue would not have been a problem were it not for the fact that the wife he chose was none other than Eleanor, the daughter of Edward I's old enemy, Simon de Montfort. Turning a member of the De Montfort family into Princess of Wales when barely ten years had passed since his death could become a hitch pennant for disaffected Edward's reign. The English boarded the ship in which Eleanor was travelling, seized her and took her to London. She would spend the next three years in the Tower.

Edward had been patient with Welsh problems, but when he decided to act he did so forcefully:in November 1276 Parliament declared war on Wales, and in less than a year the English armies (led in person by the king on the end of the attack) took back all the lands conquered by Llywelyn in the last thirty years.

The advance of the English army was preceded by a herculean engineering task in which three-meter-wide roads were built and huge tracts of forest were cut down. And Edward ordered an impressive line of castles to be erected along the border to serve as a base for the attack and to secure supplies. This done, on July 3, 1277, he advanced with his force from Worcester, while two other corps marched into Wales from the north and from the south. He was accompanied by Llywelyn's brother, Dafydd.

The advance, thanks to the measures taken by Eduardo, was rapid. The Welsh had been deprived of their way of warfare, and Llywelyn knew that he could not fight the English in the open. The turning point was the taking of the island of Anglesey, 'the barn of Wales', on which the local people depended for food. Without Anglesey, Llywelyn had to surrender.

He was forced to sign on November 9, 1277, the Treaty of Conwy, by which the work of a lifetime was nullified and by which he was forced to share his possessions in Gwynedd with his brother of he Dafydd. The English allowed him to keep the title of Prince of Wales, but more as a mockery of his new status than as a show of recognition. Llywelyn had to endure one last humiliation:his oath of homage to the King of England would no longer be taken in Wales or nearby places like Chester. The Prince of Wales had to go to London to kneel before the King of England, where he paid homage in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1277. The wedding between Llywelyn and Eleanor could now take place, but Edward did not allow them to marry in Wales as would have been normal. They had to do it in Worcester. This imposition was one of Eduardo Idio's signs that Welsh independence was over.

From that moment on, there were a few years of apparent balance between the diminished possessions of Llywelyn and his brother Dafydd and the conquests of the English in Welsh territory. But the coexistence between the English and the Welsh became more and more complicated, until finally simmering tensions erupted into open conflict in March 1282. This rebellion took place simultaneously in several places, suggesting that it was a concerted move. Its head, however, was not the nominal Prince of Wales, Llywelyn, but his brother Dafydd. In fact, it appears that Llywelyn was not even initially aware of the uprising and took some time before deciding to support it.

The main cause of the rebellion, in addition to Welsh discontent over the concessions they had been forced to make in the Treaty of Conwy, were the problems that were being generated by the presence in Wales of a large number of English settlers, with which Clashes with the Welsh multiplied, as well as with English officials and officials to guarantee the application of the laws. If a Welshman wanted to make a complaint or claim about the conduct of an Englishman, he had to go to courts that followed the English system of procedure and applied English law. This generated, in the eyes of the Welsh, a large number of injustices that affected land disputes even among the large landowners in the region. The main claim of the rebels, as Dafydd wrote to Eduardo, was to demand that the application of Welsh laws be maintained.

Edward, who had been content for the moment with the situation resulting from the Treaty of Conwy, flew into a rage, especially when he learned that the leader of the rebellion was Dafydd, whom he had taken in when he was a hopeless fugitive from his brother and who had left in a privileged position after the previous invasion of Wales. He set out to put an end to the Welsh problem once and for all.

It was a very uneven fight. The English had a whole line of castles in Wales that Edward had ordered built or reinforced after conquering them and that served as the basis for the invasion. In less than a year the English had conquered all of Wales and, with Llywelyn killed in a skirmish, the war turned into a manhunt until Dafydd was captured. The other rebels were pardoned, but Eduardo kept for the ringleader a fate of torture and execution that is very reminiscent of those who, years later, awaited another leader of an uprising against him. That rebellion took place in Scotland, and the leader answered to the name of Willam Wallace.

Continuing with his policy of symbolic gestures of which Eduardo was very much in favor, he ordered the construction of a castle (Caernarfon) in a place of high significance for the Welsh. There were the remains of the Roman fort of Segontium, which Welsh tradition said had been built by an emperor who dreamed of erecting the most magnificent fort ever seen by man there.

Caernarfon was the most impressive of the castles that marked English rule over Wales. The king was there with his wife Eleanor of Castile when she gave birth to the future Edward II. Legend has it that at the birth of his son, Edward said:"Didn't the Welsh want a prince born in Wales who didn't speak English? Well, they already have one." The anecdote is probably not true, since the first reviews that exist of it date from the sixteenth century; furthermore, at the time of his birth, Eduardo was not his father's heir, as his older brother Alfonso (so named in honor of the queen's brother, Alfonso X of Castile) was still alive.

In fact, the formal designation of Edward as Prince of Wales, in the sense that he has retained to date as heir to the crown of England, did not occur at the time of his birth but seventeen years later in a session of the English Parliament held in the city of Lincoln, in the year 1301.

In 1294 there was a final rebellion of Welsh notables against English rule. But between the fact that the most important nobles had died or disappeared after the uprising of 1282, and that the English army that went to put an end to the rebellion was the largest ever sent to Wales, the uprising's journey was very small and ended in the spring of 1295 at the Battle of Maes Moydog. In this way, Wales came to be definitively under English rule.

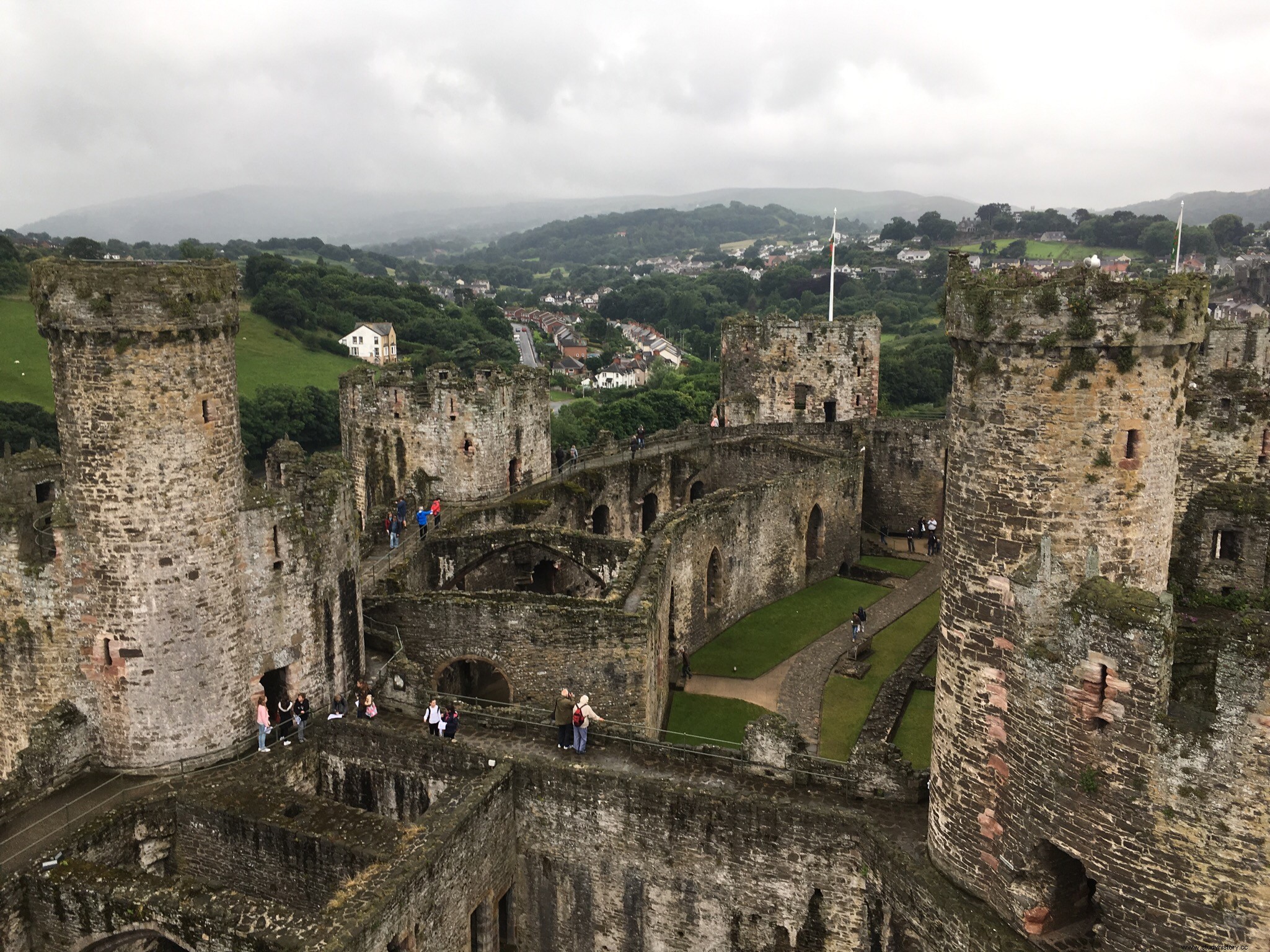

On a visit led by the English historian Marc Morris, author of biographies of William the Conqueror, John the Landless and Edward I and a work on the castles of Great Britain, he had the opportunity to visit some of the Welsh castles built by Edward I. The photographic report of the following video is the result of that visit. It should be noted that one of the castles, Dolwyddelan, predates the conquest, but it is worth it not only for its beauty, but also for being the birthplace of the grandfather of the Prince of Wales Llywelyn, of the same name and known as the Great .

Image| Author Archive