Although the best known and most popular part of the history of Alexander the Great was the expedition he led against Persia, before that he had to impose his authority over Greece and during that process, in parallel, he was forced to subdue the rebellion of the Illyrians. He could not let it grow because of the threat it posed to his rear, since at that time he was campaigning against the Thracians and to complicate matters he had just received the news of another uprising in Thebes, so he set off towards Illyria to deal with problems one at a time.

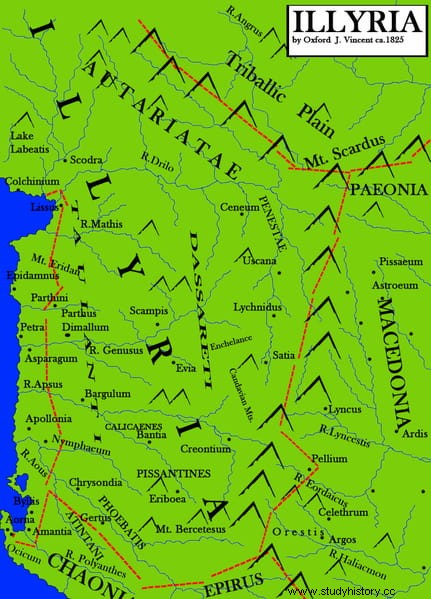

This territory located north of Epirus occupied approximately what are now the countries overlooking the Adriatic:Albania, Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia, Montenegro and the Republic of Macedonia, being mainly occupied by two peoples of Indo-European origin. The first was that of the Taulantians, a group of partially Hellenized tribes who lived a stage of certain splendor under the command of the newly crowned Glaucias. The second was made up of the Dardani, related to the previous ones but also to the Thracians; its leader at that time was Clito.

Philip, Alexander's father had subdued them but without occupying the region, since being so close to his country he could always quickly send a punitive expedition and thus avoid keeping troops in perennial garrisons that he might need elsewhere. Of course, that meant the Illyrians retained their ability to take up arms, and that was what happened when Glaucias and Cleitus reached a coalition agreement to free themselves from Macedonian rule.

As we said at the beginning, Alexander was fighting the Thracians when he found out and immediately realized the danger:since the Illyrian city of Pelion (or Pelio) constituted a strategic passage between that region and Macedonia, closing the access to a narrow gorge for which barely four men could fit at once, the loss of his control could leave him isolated in Thrace and incite the polis Greeks to turn against him; something very likely because he had just subdued them for trying when they took advantage of Philip's death, thinking that his heir would have a hard time keeping the throne.

Fortunately, the young Macedonian king had a suitable ally:Langaro, an Agrian monarch, a tribe from the border region between northern Macedonia and southern Thrace, who had remained loyal and whose contribution to the Macedonian army was very important because his warriors They made excellent light infantry:they hardly used any protection (at most a helmet and a wicker shield) but they were expert javelin throwers and carried a bundle of javelins into battle. They stood out especially in mountainous terrain where the phalanx was useless but they also fought alongside the hipaspistas (a medium-heavy infantry) and as an auxiliary complement to cavalry.

Langaro was in charge of keeping the Autarians, the most powerful Illyrian tribe, at bay, giving Alexander time to go to the region with the bulk of the army, about fifteen thousand men. So useful was it that the Macedonian showered him with favors and even promised him the hand of his half-sister Cinane (daughter of Philip and the Illyrian princess Audata), although the marriage could never take place because Langaro would become seriously ill and die. The thing is that Clito's dardanians, in effect, were already in Pelion, where Glaucias was also marching with reinforcements, so Alexander decided that it was critical to conquer that city as soon as possible.

It seemed complicated, since not only was it settled on a plateau but the surrounding mountains were also in the hands of the enemy. An enemy who, furthermore, had high morale because Clito had secured the favor of the gods by offering them three boys, three girls and three black rams as sacrifices.

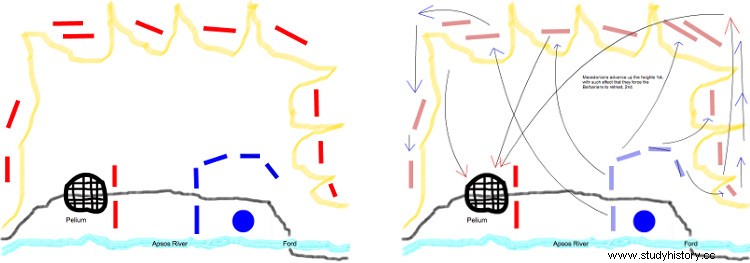

Alexander resolved first of all to clear the field of operations so that he could carry out the attack on Pelion without threat, and sent his forces to clear the surrounding heights, whose defenders had to run for cover behind the walls. He was then able to attempt the assault but it was unsuccessful, so he chose to start siege work.

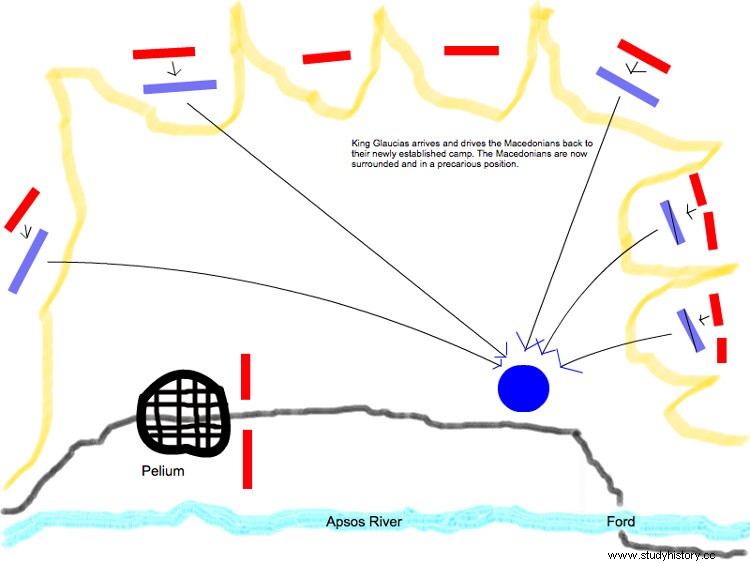

In it he was when Glaucias appeared with the reinforcement troops, leaving the Macedonian in a compromised situation:outnumbered, caught between two fires and without having had time to start the construction of ditches and parapets. He had no choice but to leave the hills from which he had driven the Dardanians the day before and barricade himself in his camp, but with the problem that he could not afford to stay there long, not only because he lacked provisions for it but also because when they found out in Thebes and Athens of his plight, they would jump at the opportunity to turn against him.

The first thing was to open a supply route in case things drag on and this mission was entrusted to Philotas, cavalry chief and hero of the future Battle of Gaugamela, who, like his father, the prestigious general Parmenion (who had subdued the Illyrians a couple of decades earlier), would be executed by Alexander in 327 BC, for refusing to continue the Asian expedition. The Agrians of Langaro, the hypaspists and the archers were in charge of protecting the march of Philotas, which Glaucias tried unsuccessfully to prevent.

Then the Macedonian dislodged the Illyrians guarding the upper part of the gorge with an unusual and disconcerting tactic:setting his phalanxes to exercise and parading in close order (one hundred and twenty men deep) across the plain accompanied on each flank by two hundred horsemen. . Forward and backward, half-turn... All without a cough being heard, in a spectacular military demonstration that surely their adversaries watched from the surrounding heights with the same mixture of fascination and fear as those who did from Pelion.

They snapped back to reality when Alexander judged that he had already reached the level of intimidation he intended and gave the order to suddenly charge at them, breaking the deathly silence with the classic Macedonian war cry "Alalalalai!" ; the others left in disarray to seek refuge in the city, leaving Philip's son, owner of the land, with hardly any casualties. The situation had been saved for the time being.

He then wrested control of the ford over the Apsos River from the Illyrians, leading his troops across the river in single file. The enemy tried to stop him but was repulsed by the archers, who shot their arrows into the water at their waists and were supported by a cavalry charge. In this way the Macedonians managed to reach the other shore, ensuring free passage to receive the supplies sent by Philotas. However, it would be unnecessary. The Illyrians had interpreted the Macedonian maneuvers as the beginning of a withdrawal and this led them to relax their vigilance; a fatal error when he is faced with a military genius who, of course, did not miss that detail.

That same night Alexander led an assault on the city with his phalanxes, Agrianians and archers, the pezhetairoi taking the initiative of the action. (Phalangite infantrymen) of Coenus (who was the son of General Polemocrates and godson of Parmenion), an elite troop that always occupied the right flank in combat, considered the most honorable on the battlefield. The attack was completely unexpected by the Illyrians, who were unable to offer an orderly resistance and ended up massacred or taken prisoner, although in pursuit of the fleeing Alexander fell from his horse and nearly broke his neck.

The fall of Pelion in just two days crumbled the resistance of Illyria and forced it to submit forever to the brilliant winner (it would even contribute a contingent to its army in 334 BC), who was already able to safely face the next chapter of that continuous and endless military campaign that was his life:crossing Thessaly to go towards Boeotia and Attica and suffocate the rebellions of Thebes and Athens, who believed that the aforementioned fall had caused his death. The first city was devastated by his tenacious resistance to set an example and the second was spared by recognizing his authority (they named him Hegemon , like his father) after he had the audacity to enter the city alone. Everything was ready for the great dream of conquering the Persian Empire, but that is another story.