Surely everyone has heard the adjective draconian/na , generally applied to laws or conditions, which the RAE defines as “excessively severe”. But do we know where that word comes from? It does so from the name of a historical character, a legislator from Ancient Greece who compiled the existing legislative codes and, foreseeing very harsh penalties for infractions, was linked to that rigor, despite the fact that in reality he barely contributed a few of his harvest. He was called Dracon.

We know very little about his life, to the point that there are those who have questioned the very existence of him, given that drakón in Greek it means snake and as the Athenians worshiped a sacred snake that was guarded in the Acropolis, it could be a metaphor of the laws. Assuming, then, that he was real, he was born in the middle of the seventh century B.C. in Attica, the Greek region located on the homonymous Aegean peninsula, which at that time was not yet fully subject to the rule of Athens but was in a progressive process of agglutination of its communities around that city. However, the aristocratic families lived outside the urban centers leading a fairly independent life and would continue to do so until the tyranny of Pisistratus and the reforms of Cleisthenes made Athens the capital.

If it really existed, Dracon would probably belong to one of those aristoi families. . But his entry into history was made as eponymous archon , a magistracy whose head was appointed by lot among the citizens who presented his candidacy and who originally shared powers with the archon basileus (a kind of king) and the polemarch archon (military chief), although later the number of archons was increased to nine, three main ones and six thesmothets or judges; Cleisthenes would add a tenth with secretary functions. It seems that Dracon was a thesmothete before being elected eponymous archon, whose functions consisted of dealing with civil administration and justice; Moreover, it seems that the Athenians entrusted the legislative reform to a group of Thesmothetes before Draco but they failed and so they decided that a single man should take charge.

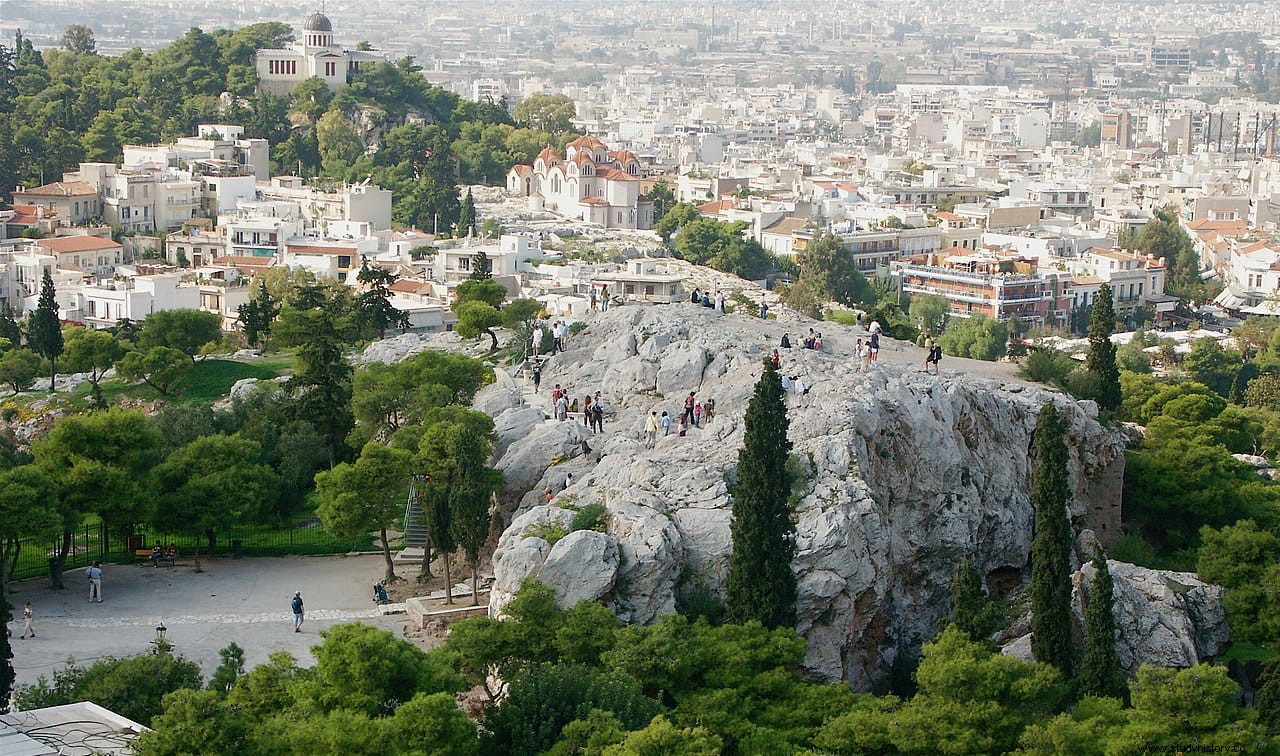

The rise to power of Dracón, the one designated for it, was determined by the tense situation that the polis was experiencing. since in 632 B.C. Archon Cilón will try to carry out a coup d'état with the support of his father-in-law Theagenes, the tyrant of Megara, to solve the struggle for power between the Eupatridae (ruling noble landowners) and the demo s (rich merchants who also aspired to their share of power). The plan did not work out as he expected because he made the mistake of employing Megarian soldiers, which especially offended the Athenians, and he had to take refuge on the Acropolis with his followers. But when they tried to escape they were discovered and killed by Megacles, another archon. Unfortunately, he did so by breaking his word to respect their lives if they surrendered, and above all on sacred ground, so he was expelled from the city and with him his family, the Alcmaeonids (it was customary that the fall from grace of a public figure implied also yours).

The Alcmaeonid clan was of great importance in Athenian politics, so its absence caused a struggle between the other lineages to fill the gap left while the demos insisted on his claims. “Most of the people were subjugated by a few, and the people had revolted against the nobles. The uproar was very strong, and for a long time they fought against each other." This is how Aristotle described things when a sector of the nobility headed by Dracón understood that they had to put a stop to that or they would be doomed to a social revolt.

Tyranny was not an option, as we saw, so the Eupatriates agreed to give up part of their prerogatives in favor of the demand of the demos of a legislative code that conferred total authority to the state in the judicial plane. Until then, disputes between families were resolved among themselves and also in a customary way, that is, with sentences derived from tradition and not from written laws. Times were changing and the blood feuds or fights that this system implied were no longer acceptable; It was necessary for the laws to be reflected in writing as a reference for everyone equally and for a court to administer justice.

Thus, around 621 or 620 B.C., what some consider to be the first constitution of Athens was born, which was written on a few axons, wooden tables -later stone- pyramidal in shape and rotating so that each of their faces could be read. . They distinguished between murder and involuntary manslaughter but, above all, their infraction was punished extremely harshly. Debts were punished with slavery -unless the creditor was of a lower class- and the death penalty was common even for minor crimes, such as theft, something that was due, according to Plutarch, to the fact that Dracón did not find a greater penalty for the debts. serious crimes. Criminal responsibility was no longer family but exclusive to the defendant, who was judged by virtue of his intention.

Judicial competence was confirmed to the Areopagus, which served to judge religious matters and deliberate crimes (murders, arson, injuries, etc.), being composed of a group of elders who would have been archons. However, blood crimes would be judged by the philobasileis , military chiefs of the tribes into which the Athenian population was divided, although beforehand it had to be established whether they had been committed voluntarily or involuntarily and that was decided by a court of fifty-one Ephetas , possibly extracted from the Areopagus. It is difficult to be more precise because the original code is lost and there are hardly any sources.

The draconian reform established four census classes of citizens and allowed access to lower magistracies for hoplites, that is, those who were not aristocrats but had enough capital to pay for full military equipment. This was one more example of the legislative attempt to limit the power of the higher hierarchies and incorporate the lower ones into political life, thus avoiding the danger that the latter might choose to do so the hard way. Paradoxically, although these laws benefited the people and curbed judicial arbitrariness, it was generally considered that the severity dictated by Dracon was excessive and he ended up expelled from Athens after undergoing the corresponding euthyna (the process by which all public officials had to account for their management before a committee made up of ten logists or accountants and ten eutino s or inspectors -one for each tribe- plus two paredroi or advisers).

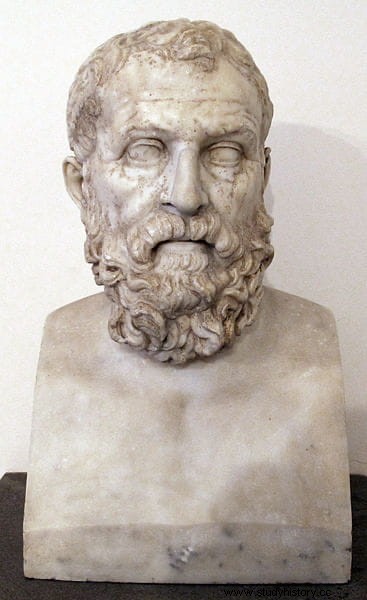

Dracón had to go into exile to Aegina, where he died, it is not known in what year exactly; It seems that he was around fifty years old. There is an unbelievable version of his death, according to which his death took place in the theater of that city due to suffocation caused by the number of layers thrown on him by a crowd of overly enthusiastic followers. The really important thing is that in 594 B.C. the Areopagus appointed archon and diallaktés (arbitrator) to Solon, one of the Seven Wise Men of Greece, granting him full powers to undertake a new legislative reform. Solon counted on "the satisfaction of the rich, for being a wealthy man, and of the poor, for the opinion of his probity" In the words of Plutarch.

With this endorsement, he repealed the laws of Dracon -except the homicide law-, he left the death penalty only for murderers (judging by the Areopagus, while the involuntary murderers would be killed by the courts of Ephetas); he established the sisakhteia (liberation of those enslaved by debts and cancellation of these); created another complementary council of the Areopagus (the Boulé, with four hundred members elected by the ekklesia and renewable each year); and granted citizenship to the lower classes, which gave them the right to access positions and honors if they met the requirement of possessing the required amount of assets.

In short, he established what is known as the timocratic system, that is, the division of society -in this case into four classes- based on their properties and income, something that Aristotle considered the purest form of government to the detriment of the democracy, which the philosopher called the degeneration of timocracy. It was an example for the entire Mediterranean, to the point that the Roman Law of the Twelve Tables was directly inspired by the new code, since Rome sent delegates to Athens to copy it. However, Draco's legal provisions regarding assassination still stood for a century and a half.