Since Tercios seem to have become fashionable for some time now, it is possible that more than one reader knows what the conch was. It was a combat tactic developed by heavy cavalry and blacksmiths between the 16th and 17th centuries against the closed formation of an enemy third or unit, whose bristling upright pikes prevented them from charging head-on against it, attacking in a row and turning in the direction of the enemy. last moment as they fired their weapons. What many do not know is that the same thing was already done in ancient times, as several authors prove, and in the Hispania that the Romans tried to conquer. Its name, derived from the town that created it, is Cantabrian circle .

The conch of the Modern Age was carried out by lines, the first of the squadron going ahead (the number of members varied between one and two hundred) to ride at a trot to the enemy (between 10 and 20 meters) and fire with the pistols; then that line turned to the left and returned to its formation, leaving the witness to the second one that came behind and then this one to the third and so on. In this way, the cavalry moved in a dynamic centripetal circle. To avoid accidents, the pistol was fired upside down, with the butt facing up.

Despite its low effectiveness, as it required getting too close to the adversary due to the limited range of the pistols, it was practiced for a long time. In the 17th century, the Swedish king Gustaf Adolphus II, a tactical revolutionary, introduced the novelty that the first two lines fired but, instead of turning, drew their sabers and charged using the effect caused by the pistols. The rest of the squad also charged forward, sword in hand, no longer firing. It didn't work against the Tercios at Nördlingen.

Actually, the so-called partum shot can also be considered a precedent. , practiced by nomadic tribes such as the Huns, Sarmatians, Armenians, Scythians, Achaemenid Persians and, obviously, Parthians. In his case there were no pistols, of course, but the compound bow; what the horsemen did was feign a retreat to provoke the enemy infantry to break their formation in pursuit. Then they would turn on the horse and, without stopping galloping, they released a shower of arrows. This technique, which required extraordinary horsemanship skills, became known to the West after the Battle of Carrhae, in which Crassus' legions fell into the trap.

Let's go back to Spain. Specifically, to the 1st century BC, when the north of the Iberian Peninsula rose up in arms against the rule of Rome. This is how Lucio Anneo Floro explains it, a Roman historian who lived in Tarraco, author of the work Epitome de Tito Livio bellorum omnium annorum DCC :

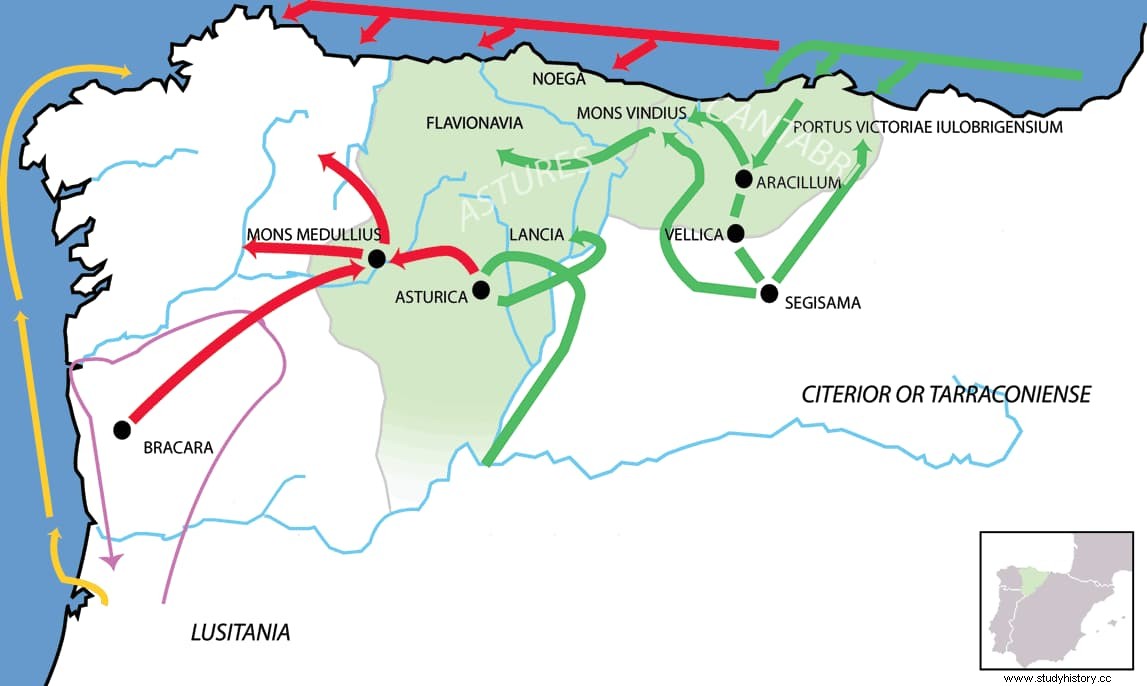

Indeed, from the year 50 B.C., when the rest of Hispania was under Roman control, Cantabria and Astures (whose territories were not limited to present-day Cantabria and Asturias but went beyond the Cantabrian mountain range, reaching parts of León, Zamora, Palencia and Burgos) remained independent and even enlisted as auxiliaries in the legions, not only during the wars between Caesar and Pompey but even before, in the Second Punic War and in the Sertorian War, resisting the conquest attempts of Tenth Brutus and Julius Caesar. But in 27 B.C. Augustus undertook a campaign against them, partly to put an end to their predatory forays to the south, partly to secure his own prestige, and partly to seize the mining riches of the area. That, of course, put its inhabitants on a war footing.

Augustus himself attended in person after symbolically opening the doors of the temple of Janus in 26 BC. -what was done to declare a state of war- and postpone his British campaign. He settled first in Tarraco, although later difficulties brought him close to the front, to the castrum of Segisama (current Sasamón, Burgos). From there he designed a double operation:the one directed by Publio Carisio from Lusitania with two legions against the Asturians and the one of the five legions that, under his direct command, entered Cantabrian territory. At the same time, there was a third way of attack from the sea, by the Aquitaine fleet.

As expected, the Roman war machine prevailed, defeating the Cantabrians in Amaya and the Mave Valley, the survivors taking refuge on Mount Vindus to, according to legend, end up immolating themselves. Later, Gaius Antistius Vetus laid siege to the hill fort of Aracillum, whose defenders met the same end. The subsequent capture of Castro Urdiales practically pacified the region, so Augustus's troops could go to reinforce those of Publio Carisio, who had to face an alliance of Asturian tribes. The Romans, warned by the brigaecini , gave a coup de mano and defeated the enemy in Brigaecium and Lancia, pushing it to the other side of the Cantabrian mountain range.

The Asturian-Cantabrian wars would still last because, after a brief rest, the legions entered Transmontane Asturias to finish the job. After overcoming the strategic enclave of La Carisa, they continued unstoppably towards the coast, ending the campaign in 24 BC. Or so they thought, because later there was a new rebellion that was brutally suppressed, causing the general uprising. But in the battles of Mount Medullius and Bergidum, the Astures lost again and the legions once again occupied the region, reaching Oppidum Noega (Gijón) and founding Lucus Asturum, in addition to building a road, the Via de la Mesa, which served them to send troops quickly. The Asturian-Cantabrian wars ended in 19 BC, leaving only small occasional embers that did not constitute a major danger.

But some of the tactics used transcended in history. One of them was the so-called Cantabrian onslaught , whose historiographic name would be pubes caterva . It was described by Silius Italicus, explaining that it consisted of the charge of a battalion of warriors on foot formed in a wedge with their chief in front wielding a two-edged axe. Gauls and Celtiberians, says Flavio Vegecio Renato, also practiced it massively, with thousands of men; just like the Germans, according to Tacitus, who gives his denomination in those latitudes:svinfylking (pig snout). Given that a chief stood at the apex of the wedge, the position of greatest risk, his probable death demoralized the rest, as happened with the Cantabrian Laro (although in his case he did not command a crowd but his men adopted a defensive formation).

Attacking running towards the adversary could also be done in open formation, as Tito Livio wrote that the Hispanics used to do. Apparently, it was a tactic linked to a religious dance called tripudium Hispanorum , because they also did it by singing a song, although in that case they did not run but rather paced rhythmically, hitting the ground with their feet and making their shields collide; something that was also practiced in Germany under the name of barditus . Now, all this was an infantry thing. And the cavalry? Did you also have specific methods to deal with the enemy? As we saw at the beginning, yes.

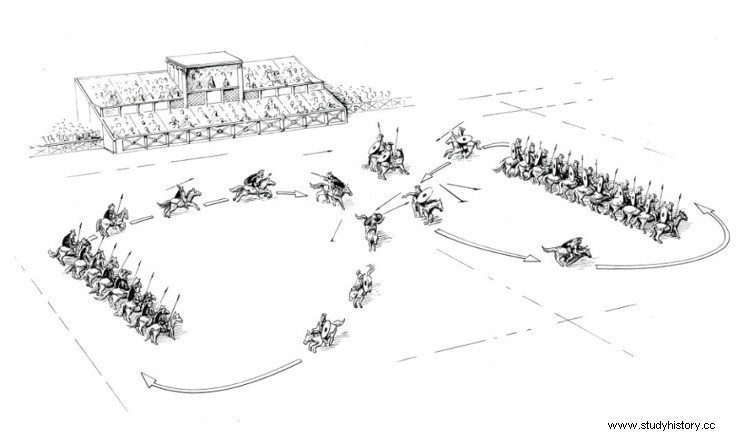

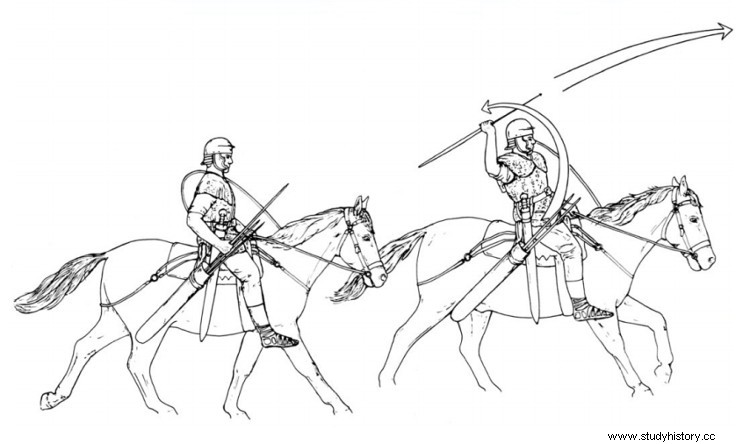

The cantabricus circulus or cantabricus impetus It owes its name to the fact that the horsemen were organized into two large groups that converged at a trot towards the enemy formation, each one on one side. Before reaching the clash with the shield wall, they performed a dextratio or turn to the right (it was easier than to the left), each throwing a dart and shielding themselves from the expected response with their shields to fall back and start again, thus forging a circle (hence the name) of attack continuous. This allowed a close formation of the rival to be subjected to a constant rain of projectiles, since each horseman took advantage of his retreat to rearm (they carried a full quiver) and recharge against him, preventing him from answering the fire .

The most common was to use darts, a type of throwing weapon, similar to a javelin but finer and smaller -although not so small as to be able to shoot it with a bow-, which had stabilizing feathers on its tail, like arrows. Each rider could throw between fifteen and twenty darts. However, depending on the circumstances, spears, arrows or even stones could also be used; The case was to prevent the rival soldiers from using their weapons, especially the archers, forcing them to remain behind the shields and preventing them from advancing either.

Lucius Flavius Arrian, a Greek historian and philosopher who lived between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, and was a consul, leading a campaign against the Alans, reviews the use of the Cantabrian circle by the Romans themselves. In his work Ars tactic, explains various cavalry tactics such as the petrines , the toloutegon and thexynema or testudo , to which others were added in Hadrian's time. One of the ones he describes is the Cantabrian circle (also called Cantabrian rush, Cantabrian onslaught, Cantabrian charge, etc.), common in the hippika gymnasia (equestrian exercises), as it required great skill on horseback. The steles of San Vicente de Toranzo (Cantabria), Borobia (Soria) and Iol Caesarea (Algeria) archaeologically document this tactic.

So does the aforementioned Emperor Hadrian, a friend of the above, in his adlocutio (speech) to the Legio III Augusta of Lambaesis, Numidia (Algeria), to which he made an inspection visit attending a s imulacra pugnae (combat exercises) of the Roman cavalry and writing down how an auxiliary cohort (presumably the Cohors VI Commagenorum equitata , which was Syrian but may have been reinforced with Hispanic warriors) efficiently performed what he called a Cantabricus densus :

It referred to a formation in which the horsemen were close together, packed together, using various types of thrown weapons (lapides and missilia) and riding short, rustic horses. From the adlocutio it follows that in the Cantabricus densus Light infantrymen could also participate -or perhaps they were the horsemen themselves who dismounted- to shoot stones with slingshots. In any case, the victors had adopted the tactics of the vanquished.