Not long ago, in the article dedicated to the extravagant Russian masquerade ball that inspired the costumes for the movie The Phantom Menace , we reported that Maria Miloslavskaya, the first wife of Tsar Alexios I (the father of Peter I the Great ) and mother of Tsar Fyodor III, had been chosen as royal spouse for her beauty among two hundred candidates from the aristocracy summoned ad hoc in the court. A curious custom called Смотр невест, that is, bridal show, which was actually of Byzantine origin and through which the first queen to experience it, Irene of Athens, Empress of Byzantium between 797 and 802, would have had to go.

Sofia Palaiologos, niece of Constantine XI (last emperor of Byzantium), was the one who in the fifteenth century brought this peculiar tradition to Russian soil after marrying Ivan III and drenching the Moscow court with the pomp typical of her country of origin, turning it into the so-calledThird Rome (the second was Constantinople). Irene, whose life was more than half a millennium earlier, enjoyed even more power than her, despite living in a world dominated by men who sought to take advantage of her condition. She was of noble blood, from the illustrious Sarantapechos family, a dynasty that wielded considerable influence in central Greece. However, she had been orphaned as a child, which limited her economic possibilities.

However, she had one trick:an extraordinary beauty that favored her being taken to the court of Constantinople by order of Emperor Constantine V to marry her son, her Leon. However, beauty could not hide important differences, both financially and in their respective beliefs, which in principle should be an obstacle to this marriage:while Constantine was an active iconoclast (his father, Leo III, had banned images of Christ and the saints for considering them heretical), Irene confirmed the opposite. The issue may seem trivial but it was not at a time when faith was closely linked to imperial power.

For this reason, it is believed that Irene was one of the candidates included in a bridal show, in which a number of young people from all over the country, famous for her beauty, paraded before what could be her future husband. In reality, it is a speculation deduced from the mentioned context because there is no documentary evidence to prove it and there are even authors who believe that this practice is an invention of the 9th century historians. However, it was not something exclusive to the Byzantine Empire, since it was also practiced in imperial China since the Song dynasty and, as we have seen, it would be exported to Russia, where it lasted until the wedding of Ivan V and Praskovia Saltykova in 1684, when it had already been hundreds of years since he had ended up in the place of origin.

If it really happened, Irene would have started the custom; if not, her honor would go to her daughter-in-law, Maria of Amnia, chosen by her from among thirteen women for her son Constantine VI by her in 788 AD. Despite everything, the choice did not guarantee marital success and the best proof was Constantine himself, who abandoned Mary and, despite having two daughters (whom he sent to a convent) and ignoring the opposition of the Church Orthodox, he divorced her to remarry Theodote, a kubikularia (maid of honor) of her mother.

In any case, Constantine was the first child of Irene and Leo, born in 771 AD. four years before the emperor died and his heir ascended the throne as Leo IV the Khazar . The nickname came from his mother, the Khazarian princess Tzitzak (also renamed Irene); the Khazars were a Turkic people from Central Asia who granted her hand to the late Emperor Constantine to form an alliance between the two nations. León reigned barely five years, since he died of tuberculosis in 780; at least alone, since his father had associated him with the throne since he was a child, just as he did with his son in 776 to try to guarantee his succession and avoid the ambitions in this regard of his uncles, the Caesars Nicephorus and Constantine (still Thus, a conspiracy of these was discovered that led to his exile).

The reign of León contrasted with that of his father in loosening the persecution of the iconophiles, surely out of deference to his wife, to the point that he even named one of them, Paul of Cyprus, patriarch of the Church. However, one thing was tolerance and another to change the character of the imperial religion, which officially continued to be iconoclastic and eventually persecutions were practiced against those who opposed it. The hardest and most decisive one took place when icons were discovered in Irene's rooms, with whom he refused to have conjugal relations again. There are doubts about the veracity of this episode because it is too similar to that of Empress Theodora, wife of Theophilus, who a few decades later would put an end to the iconoclasm. Whether true or not, the issue ended with the emperor's death and Irene's conversion into regent, since her son was only nine years old.

Barely a month had passed when he had to face the first palace conspiracy, led by his brother-in-law Nicephorus. He was able to prevent it and, to prevent further attempts, he replaced all the imperial dignitaries with like-minded people; trying to ingratiate herself with her in-laws, she also offered Anthousa, León's sister, to be co-regent, although she refused. That left her alone on the throne, since she only had the precedent of Martina, the second wife of Emperor Heraclius; not a reassuring reference because she had only been able to support herself for a year before her tongue was cut out and she was banished to Rhodes.

Something like this was expected to happen with Irene as well, so she sought out strong allies. To do this, he established a diplomatic relationship with the Pope and arranged the marriage of his son with the Frankish princess Rotruda, six-year-old daughter of Charlemagne and Hildegard of Vinzgouw, even sending him a Greek teacher, although she herself would break the agreement some time later, when Franks and Byzantines went to war. None of this prevented a new conspiracy, this time led by the stratego Elpidio, who took up arms in Sicily. Defeated by a Byzantine fleet, he took refuge in the Abbasid Caliphate, which he convinced to invade Byzantine possessions in Anatolia. Irene had to stop the aggressive expansion through the Balkans that she had promoted and agree to pay a huge annual tribute for the Muslims to withdraw.

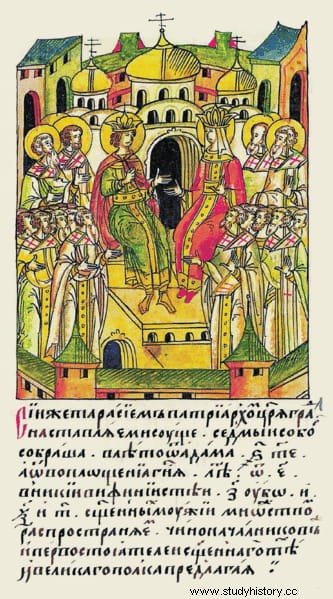

Meanwhile, as expected, the regent reinstated the cult of icons by holding two councils, that of Constantinople in 786 and that of Nicaea a year later, favoring during the latter an approximation to the papacy. But Irene's autocratic tendency was beginning to be an annoyance to Constantino, who was growing up and little by little tried to free himself from his mother's tutelage; we have already seen how he divorced the wife she had sought him out. Although initially all this was counterproductive, increasing Irene's personalism, finally an insurrection took place -supported by Armenians- that put an end to her regency.

Mother and son would share the throne but the proverbial intriguing image of the Byzantine empire is not gratuitous and in 797 Irene led a coup against it. Constantine VI had to flee to the Bosphorus, but he was overtaken and sent back to Constantinople, where his eyes were gouged out; an eye infection killed him in the following days, coinciding with a solar eclipse that plunged the Earth into darkness, which was considered a sign of the horror that this act had provoked in God. Irene was left as sole ruler and eventually dared to use the title of basileu s instead of the female version of her, basilissa , as if it were a new Hatshepsut, that Egyptian queen who called herself pharaoh and wore a false beard.

The all-embracing power that he reached was only unparalleled in the West in the person of Charlemagne and both empires experienced a fierce rivalry, especially when Pope Leo III, in the absence of a male emperor in Constantinople, appointed the Frankish king for it, something that the Byzantines considered an infamy. Charlemagne was never able to exercise that position, obviously, so Irene continued to rule. Now, rare was the emperor who ended his days quietly. Another coup organized by patricians and eunuchs in 802 was finally successful and Irene was overthrown and replaced by her genikos logothetēs (finance minister), who ascended the throne as Nicephorus I.

Her life was spared but she was confined to Lesbos, where she had to work spinning wool to earn her bread. Her exile did not last long, as she died in 803. Paradoxically, the memory of her that she left behind was fundamentally religious, such as that she restored the cult of icons and returned her dignity to the monasteries. .