Some time ago we dedicated an article to Cola di Rienzo, an apostolic notary of humble origins who lived in the 14th century and was determined to return Rome to its former imperial splendor through a series of revolutionary measures that included the banning of the nobles of the municipal government and his appointment as tribune. Rienzo, who aspired to be novus dux from a federation of Italian republics, he ended up a paranoid tyrant, excommunicated by the Pope, deposed, and executed.

Well, it is said that Rienzo was also the one who convinced a man named Giannino Baglioni that he was actually John I, posthumous son of King Louis X of France and therefore heir to the throne. The problem was that Juan I had died five days after being born.

Obviously, Cola di Rienzo's intention in radically changing Baglioni's life was to find an ally in the neighboring country that would strengthen his own position in Rome, as we saw increasingly unstable. Because it was no more than a simple merchant to whom Rienzo discovered a secret that he claimed to keep for years, when a French monk residing in Siena entrusted it to him:Queen Clemence of Hungary, wife of the aforementioned Louis X the Obstinate her, she gave birth to a son on the night of November 14-15, 1316, four months after her father passed away. That child was destined to wear the crown, since his older stepsister, Juana, who the monarch had had with his first wife, Margarita de Borgoña, was automatically relegated for being a woman and a minor but also for suspecting that in reality she was not. daughter of Luis.

Indeed, the newborn, baptized with the name of Juan I, was crowned immediately, but in medieval Europe the infant mortality rate was very high and the little one could only reign for five days (under the regency of his uncle Felipe de Poitiers, Of course). It is not known what was the cause of death; any illness of the time could end her life, although there were also rumors of murder by poisoning, the hardest being attributed to Matilde de Artois, Juana's mother, who would have pierced the still soft bones of her skull with a long pin. In any case, the unfortunate baby was given the nickname of the Posthumous and France found itself for the first time in its history without a male heir since the days of Hugh Capet.

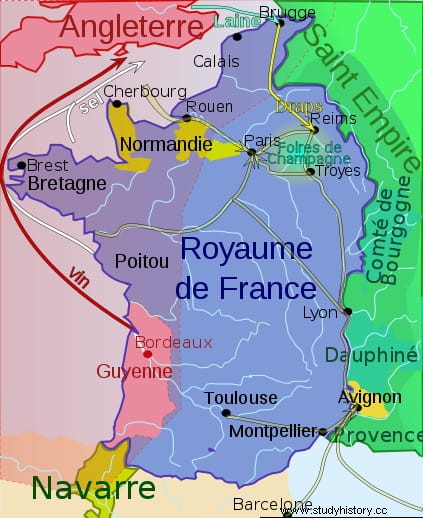

Duke Odon of Burgundy proposed Juana as a candidate, who after all was his niece, but the one who gave the crown in January 1317 was the regent, who became King Philip V. Everything seemed resolved and not just Odon. ended up accepting in exchange for privileges but the so-called law of men or Salic law was restored, a rule of Frankish origin that had not been in force since the Capetian dynasty was founded in the year 987 and for which it was excluded from the throne to women to prevent one dynasty from displacing another by descent. Paradoxically, that would rule out Philip's four daughters from succession, when he died of dysentery six years later, and his brother, Charles IV, should be crowned.

Charles didn't reign long either, another six years, dying in 1328. As with Louis X, his wife, Joan of Evreux, was pregnant at the time and everyone was anxiously awaiting childbirth because the Capetian "curse" continued:the king's first wife, Blanche of Burgundy, was repudiated as an adulteress and the second, Marie of Luxemburg, had given him a daughter who died shortly after birth, dying herself shortly after when her carriage overturned... just when she was pregnant with a child. male. With Juana de Evreux he had also had a daughter, so the expectation for a child was great. But she was a girl again and once again a regent had to come to the throne, Felipe de Valois, who put an end to the Capetian dynasty and inaugurated the Valois dynasty.

He was called Felipe VI and died in 1350 after a chaotic reign in which the defeat to the English at the Battle of Crécy, the Great Jacquerie revolt and an outbreak of the Black Death were his most striking chapters. This time there was a male successor, his eldest son, who was crowned Juan II and would earn the nickname of el Bueno by a successful government that contrasted with that of his father, to the point that this weighed more than having been taken prisoner in Poitiers. It was during the reign of John II that Cola di Renzo convinced Giannino Baglioni that he was John I the Posthumous and he had to claim the dynastic rights from him. How was that possible?

Well, because a change of newborns would have been made to protect him from a poisoning that, if so, ultimately killed his substitute, the son of a nurse named Maria de Crassey who was married to a Sienese banker. To that city he sent the royal chamberlain to the real Juan, leaving him in the custody of several monks; one of them would be the one who contacted Cola di Rienzo to tell him the truth. Thus, the ambitious tribune financed Baglioni's aspirations, although his plan was interrupted because his clumsy politics made him so hateful that he ended up causing the very people who had extolled him to take up arms against him and lynch him. It was the year 1354 and the presumed incarnation of John the Posthumous he was left without his great supporter.

However, he decided to go ahead taking advantage of Juan el Bueno he was a prisoner in England. In 1356 he traveled to Hungary to obtain royal recognition; not from his mother, who had been dead for twenty-eight years, but from his cousin Louis I, the king. Louis accepted her story, either because he truly believed it, or because of her physical resemblance to her late aunt, or because of the strategic interest of restoring a relative to the French throne. Baglioni remained at the Hungarian court until 1360, when he went to Avignon to see the Pope and for him to vouch for his identity -and, consequently, his claim- of him. He was counting for this on the fact that Innocent VI had pardoned Cola di Rienzo from the death sentence to which his predecessor, Clement V, had condemned him, after accusing him of heresy for a grotesque coronation ceremony. In reality, that pope feared the power he had achieved while Innocent VI, on the other hand, was more concerned with the Roman aristocratic clans.

Unfortunately, Baglioni was met by the pontiff's refusal to even receive him. In fact, that was the tone everywhere; no one wanted to complicate their lives or activate the always dangerous game of successions; the Valois were already seated on the throne of France and the Capetians were history. That is why the insistence of that annoying character, who did not hesitate to alter and falsify documents that endorse his presumed identity or squander his fortune or postpone his family, ended as expected:the army of mercenaries he gathered to try to recover by The force that he believed was his was easily defeated in Provence and he spent the rest of his days in a cell in Naples or, according to versions, a refugee in Hungary. He died in 1363.

This exciting story seems worthy of Alexander Dumas and constitutes one more episode of what was later called Sebastianism, a messianic movement born in Portugal in the 16th century and based on the hope that King Sebastian I, who died in the battle of Alcázarquivir but without his body ever being found, he would return one day to restore order and seize the crown from Philip II. Sebastianism was embodied in a famous case, that of the Madrigal Pastry Chef, in what was nothing more than the reflection of a quite frequent trend in the towns, as other cases had shown, since Antiquity; We are talking about some of them here, such as the Undercover or the impostors who pretended to be Nero.

The story of Giannino Baglioni really happened, although it is enriched -and distorted-, by a multitude of books of all kinds that have dealt with the subject, some with more imagination than others:Tommaso di Carpegna Falconieri (L' uomo che si credeva re di France:a medieval story ), Maurice Druon (The Cursed Kings), etc. For example, Marie de Cressay appears in Druon's novel but her real name was Marie de Carsix and her husband had less power than she claims. Also, the participation of Cola di Rienzo in this matter is not clear. Remember that se non è vero, è ben trovato .