Deaths are always unfortunate and even more so if they occur as a result of an accident. But, sometimes, there are deaths that have especially humiliating characteristics and probably among the worst recorded in history is the incident that occurred in Erfurt in the Middle Ages, when dozens of members of the court of Henry VI perished when the floor of the building collapsed. where were you. Many lost their lives due to the fall, but others drowned in excrement, as they fell into a septic tank.

Henry of Hohenstaufen was born in Nijmegen in 1165. He was the son of Frederick I Barbarossa , holder of the Holy Roman Empire, which is why he was appointed King of Romans when he was barely four years old and began to accompany his father on his campaigns, first in 1176 against the Lombard League, and later in the repression of the rebellion of Henry the Lion , all this in the context of the struggles between Guelphs and Ghibellines. Such precocity gave him extensive military experience that would come in handy when Frederick I Barbarossa joined the Third Crusade, leaving him in charge of the Imperial government.

That initiation into political and war issues was made compatible with a careful education that made him learn Latin and law; as well as one of his tutors was the minnesänger (troubadour) Friedrich von Hausen, also composed poems. Likewise, in 1186 he would marry Princess Constance of Sicily in Milan, who was a decade older than him but was a good match for being the posthumous daughter of Roger II, the Norman monarch of Sicily, and therefore his heiress, since the Roger's successor, William II the Good , he had no offspring. Henry would end up taking over from his father as emperor in 1191.

But all this happened after the tragic accident mentioned, which occurred on July 26, 1184, during another of those campaigns that he headed; specifically, against Poland, although what led him to settle with the court in Erfurt, in the Duchy of Thuringia, was to try to mediate the dispute between his cousin, the landgrave (Duke) Ludwig III and the Archbishop of Mainz, Conrad of Wittelsbach, after the fall from grace of Duke Heinrich the Lion . He had supported the Guelph cause but then could not come to the aid of Barbarossa before the Lombards and both fell out; after defeating him, the emperor banished him.

This altered the stability in a region divided into a multitude of small domains that often collided due to rivalry among themselves or due to the different candidates that were presented for election to the imperial throne. In this case, Thuringia and Mainz clashed when the archbishop of the latter began in 1180 the construction of a castle on a hill in Heiligenburg, a site very close to the Thuringian border. The project was due to the fear of an invasion by Luis III but he considered it a provocation and, at the same time, a threat. This is how things were when Henry arrived in Erfurt (the same city where in 1507 he would be ordained a Luther priest) to resolve the conflict; there he had been sentenced years ago the Lion .

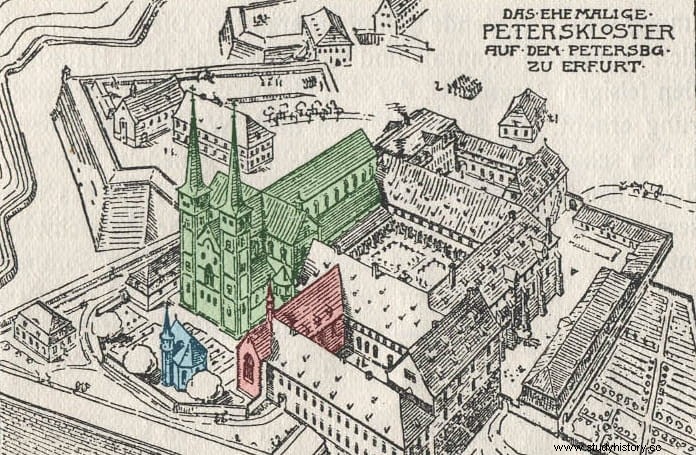

The Diet, called by himself, took place on the upper floor of the rectory of the Peterskirche, the church of the monastery of Saint Peter, the oldest building in the Citadel Petersberg, germ of the current cathedral and seat of a Benedictine monastic community. . His entourage and representatives of both disputing parties, invited to discuss the matter, gathered together. It is difficult to know exactly how many people there were, but there were many more than a hundred, since the dispute had branched out, involving other gentlemen who took sides on one side or the other. There were so many that the floor beams, probably rotten, could not withstand the weight and everything collapsed.

The weight was such that when people arrived, pieces of wood and stones hit the surface of the first floor, they also sank it and continued to fall to the basement of the building, where the latrines were located and below a large septic tank that received the waste from these and from the aborteker (Protruding structures from the façade that were used as dressing rooms and toilets, being equipped with a lower opening through which the feces fell into a small well that channeled them to the aforementioned pit below). In any case, the latrines also gave way and, due to the force of gravity, everyone ended up submerged in a large fecal pool, in what must have been a vision halfway between the bizarre and the tragic.

Because, according to contemporary sources, there were more than sixty fatalities, some due to the blows they received from the rubble falling on them but many drowned in the tons of excrement accumulated over the years (they used to be emptied not often but when they were filled) . Among those who lost their lives so dishonorably were Gozmar III, Count of Ziegenhain; Beringer I von Meldigen; the graph Friedrich of Abinberg; the graph Heinrich von Schwarzburg; the burgrave Friedrich von Kirchberg; and the burgrave Burchard von der Wartburg (graf was the equivalent of earl and burgrave a noble title less than graf but greater than baron, used to designate the lord of a castle or a city).

Others were luckier, only getting hurt or even getting away with minor bruises. This was the case of Luis III, who, although he fell into the cesspool, was able to get out and overcome the imaginable infections that he may have suffered from wounds and scrapes. Also surviving was his adversary, Archbishop Conrad, who, sitting on a window sill, was able to grab onto the stained glass frame and hold on until rescued. Henry VI himself was saved for the same reason, staying there until they could lower him down by a ladder. By the way, he left the city immediately.

Of course, the Chronicle of Saint Peter of Erfurt he avoided going into eschatological details and dispatched the accident with more elegance than it really was; it does not say how the king survived and euphemistically describes the fate of the less fortunate:

This opens the imagination to an interesting possibility:that at the moment of the collapse the king was sitting precisely on a brick latrine, which would have saved him from falling with the others by being on the outer wall. Ironically, his physiological need would have thus determined the border between living and dying, just as that of the members of the community accumulated over time killed part of his subjects.