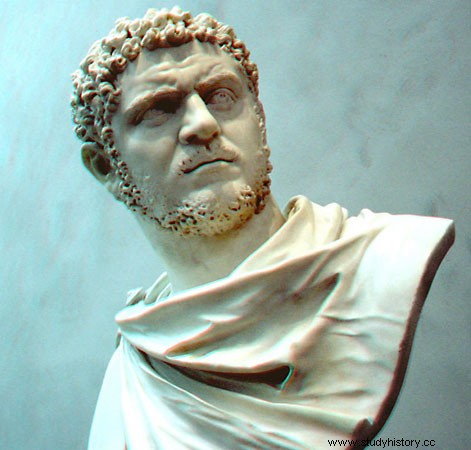

Caracalla (April 4, 188 – April 8, 217), born Lucius Septimius Bassianus then called Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Augustus, was a Roman emperor, who reigned from 211 to 217. He authored the Edict of Caracalla which extended citizenship Empire to all inhabitants of the Roman Empire.

Childhood

Of Punic and Berber origin by his father Septimius Severus and Syrian4 by his mother Julia Domna, he was born in 188 in Lugdunum (now Lyon), in the area of the current Saint-Pierre palace, his father being then governor of the Gauls. Baptized Lucius Septimius Bassianus, he was later renamed Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, in order to be closer to the Antonine dynasty. His nickname Caracalla comes from a type of Gallic hooded garment with long sleeves that he used to wear from the age of twelve.

The conquest of power

Septimius Severus associated his sons, Caracalla in 198 and Geta in 209, with the throne, naming them Augustus. When Septimius Severus died in 211, his soldiers insisted on respecting his will, forcing Caracalla to share power with his brother Publius Septimius Geta. Once peace returned, the army demobilized, and the imperial family returned to Rome, he himself assassinated Geta with a sword to the throat, taking refuge in the arms of their own mother, Julia Domna, who was trying to probably to reconcile them. Before the praetorians and then before the Senate, he justifies his conduct on the pretext of a plot that his brother allegedly fomented.

Caracalla then orders the Senate to pronounce the damnatio memoriae of Geta:he has his brother's name erased from the monuments of Rome and even forbids, under pain of the worst tortures, that it be pronounced in his presence. Nothing should evoke its existence. He then engaged in a series of systematic murders (20,000 according to Dion Cassius) targeting Geta's friends, relations and supporters or possible competitors (including a grandson of Marcus Aurelius).

The Reign

Domestic politics

His domestic policy, inspired by his mother and his father's jurists, hardly differs from that of Septimius Severus with more egalitarian aspects. It is difficult to specify what his personal role is and there is a tendency, as in the times of Nero or Commodus, to attribute the best to his advisers and the worst to himself. In general, Julia Domna directs internal and administrative affairs and leaves the conduct of the war to her son.

Identification with Alexander the Great

Caracalla is renowned for the great admiration he has for Alexander the Great to the point of identifying with the Macedonian conqueror, declaring himself the "new Alexander". In Alexandria, he pays homage to the tomb of Alexander - which he had probably already visited while accompanying his father Septimius Severus - where the mummified body is found, which he covers with his imperial mantle before closing it definitively after his passage.

He set up an army of more than 16,000 men equipped like the ancient Macedonian Phalangists called "Alexander's phalanx", as well as a "Laconian battalion of Pitana" made up of young Spartans. He won several victories against the Parthians, the "new Persians", allowing the annexation of Osrhoene. During this campaign in the East, he himself dresses in Macedonian clothes and asks his generals to take the name of Alexander's generals.

The massacres of Alexandria

The displacement of Caracalla in Alexandria from December 215 to April 216 is, in spite of a sumptuous reception reserved by the Alexandrians, the occasion of several massacres within the local population. The reasons for this are not clear:they may have been motivated by the local population's stated preference for his brother Geta or even by the riots that preceded his arrival. But the emperor, of a sickly susceptibility, also seems to have been the object of satire and mockery from the population for his identification with Alexander or for his small size.

A first massacre concerns a religious delegation that came to meet him, which the emperor may have considered as an Alexandrian embassy when he had forbidden any embassy since 213. According to Herodian, the emperor then unleashed his troops on the city, which sacked it, carrying out a massacre so appalling "that the streams of blood, crossing the esplanade, went to redden the mouth, however very vast, of the Nile". A second massacre concerns the small entrepreneurs of the city who had not delivered statues of the emperor on time. Finally, a third massacre took place in the spring of 216 which concerned the Alexandrian youth who had made fun of Caracalla's claims to identify with Alexander and to disguise himself in the effigy of the illustrious conqueror. These massacres are further accompanied by an edict of 215 which orders the mass expulsion of Egyptians from the city.

The toll of the massacre is difficult to assess:perhaps 15,000 dead, a figure that varies from one historian to another. The figure of 100,000 dead was put forward. The massacres affected not only the city of Alexandria, but also its suburbs, the surrounding villages, and the entire Nile delta. The elite and intellectuals of Alexandria are decimated. Many monuments or buildings were destroyed. The history of the city will be forgotten and will no longer be transmitted to the rest of the population, so that, for example, around 300 we will no longer be able to locate where the tomb of Alexander the Great is. Alexandria loses its former grandeur, and will no longer be anything but a modest port which will transport cereals from the country to the rest of the empire. Another consequence:Demotic (or Coptic) imposes itself as the majority language of Alexandria, and all of Egypt, with Greek declining sharply in favor of Latin. It will be necessary to wait until the beginning of the 4th century to see a final burst of Greek in Alexandria.

The defense of borders

Caracalla spends most of his time with his troops and in war.

Aureus in the likeness of Caracalla.Date:204 Reverse Description:Victoria (Victory) standing left draped, walking on the left, holding a crown in the outstretched right hand and a palm in the left hand. Reverse translation:“Victoria Parthica Maxima”, (The Great Parthian Victory). Obverse description:Laureate, draped and cuirassed bust to the right, seen from three quarters behind.

From 213, Caracalla led several campaigns against the Alamanni on both the Rhine and the Danube. Victorious on the Main, he took the nickname of Germanicus Maximus and ensured twenty years of peace on the western front, until the reign of Severus Alexander.

In 216, he went to war against the Parthian kingdom and sent an army to Armenia. During his campaign, Caracalla asked in marriage the daughter of Artaban, the king of Parthia. He obtained it and accompanied by his entire army, went to Mesopotamia to celebrate the imperial wedding. When the crowd, civilians and soldiers alike, had gathered for the feast, near Ctesiphon, their capital, Caracalla gave a signal and the scenario of the massacre of Alexandria was repeated:the Roman soldiers rushed on the Parthians and slaughtered them en masse. . The Parthian king narrowly escaped and thought only of revenge for Roman duplicity.

The Antonine Constitution:the end of centuries-old discrimination

In 212, Caracalla granted Roman citizenship (constitutio antoniniana) to all free inhabitants of the Empire. New citizens can retain their law and customs as long as they wish:this measure does not impose Roman private law in any way, as various examples prove:

Egypt delivered after 212 many documents where the new Romans maintained their local, Egyptian and Greek traditions;

an inscription dated to the reign of Gordian III (238-244) gives expressly to the customs the value of local laws;

Justinian denounces in 535-536 the survival in Mesopotamia of consanguineous marriage, considered incestuous by Roman laws, although in 295 Diocletian and Maximian had prohibited it in very forceful terms.

The reasons for this edict have been much discussed, all the more fiercely because the ancient authors have spoken very little about it. Four centuries later, the principle of universal citizenship is so taken for granted that the Justinian Code did not see fit to repeat the text. We have a unique copy in the Papyrus Giessen which begins:"I grant Roman citizenship to all foreigners domiciled in the territory of the Empire...". Several reasons seem to have to be taken into account:

Dion Cassius, opponent of the emperor, affirms that peregrines who have become Roman citizens must pay the inheritance tax which weighed only on Roman citizens and whose rate Caracalla has just increased from 5 to 10%;

the jurist Ulpian believes that an Empire where the status of persons is more uniform lightens the task of offices and courts. However, the need for lawyers and notaries is felt to the point that, to meet new needs, the law school of Beirut is organized;

certain historians relying on the Papyrus Giessen put forward the idea that Caracalla wants to achieve the unity of the faithful before the gods of Rome. Caracalla feels a real admiration for Alexander the Great:perhaps the emperor intends to reign over a unified world.

The edict results in the abandonment of the mention of the tribe in the civil status and the attribution to all new citizens of the tria nomina.

There is no factual basis and even anachronism to see in this edict the desire to create universal citizenship. The edict, however, remains cited as an example by defenders, in the 21st century, of an extension of political rights to all the inhabitants of a given country.

Death

Caracalla became during his reign a real military tyrant particularly unpopular (except with the soldiers). While he was traveling from Edessa to Parthia to wage war there, he was assassinated near Harran on April 8, 217, with a sword thrust by Martialis. Praetorian prefect Macrin, often suspected (rightly) of having ordered the assassination, succeeded him.

Caracalla's body was cremated (or perhaps simply buried, as his funeral was held discreetly), and his ashes were placed in Hadrian's Mausoleum.

Successive names

188, born Lucius Septimius Bassianus

196, made Caesar by his father:Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Caesar

198, made Augustus by his father:Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus

198, following his father's victory over the Parthians:Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius Augustus Parthicus Maximus

200, takes the nickname Felix:Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus Parthicus Maximus

209, following his father's victory over the Caledonians:Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus Parthicus Maximus Britannicus Maximus

211, accedes to the Empire:Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus Parthicus Maximus Britannicus Maximus Germanicus Maximus

217, title on his death:Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus Parthicus Maximus Britannicus Maximus Germanicus Maximus, Pontifex Maximus, Tribuniciae Potestatis XX, Imperator III, Consul IV, Pater Patriae.