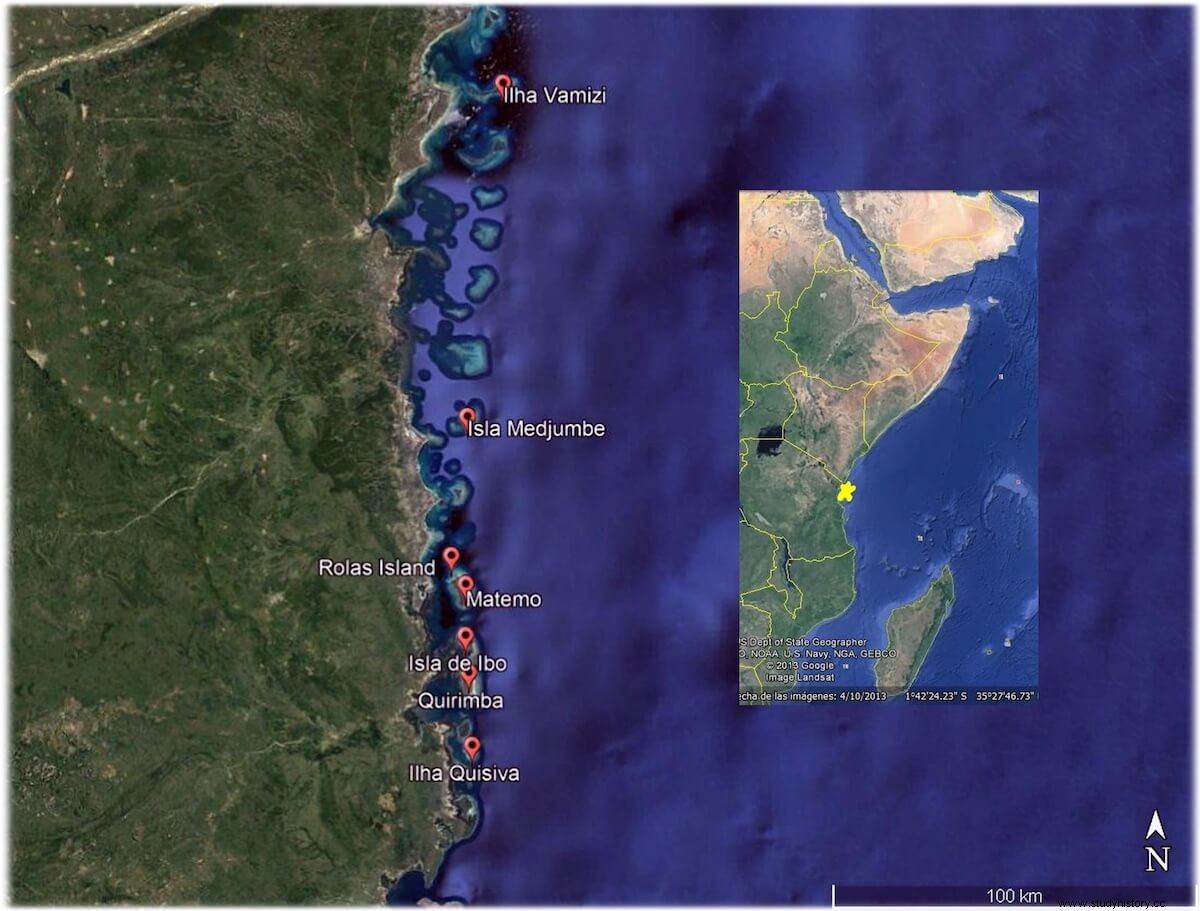

In 2015 we started a research project in the Quirimbas archipelago, north of Mozambique[1] (Fig.1). His goal was to learn about the role of this area, hitherto considered secondary, within the Swahili trade. Swahili are the populations that occupied the coastal and pre-coastal strip that extends from Somalia to Mozambique, in addition to the islands of Zanzibar, Madagascar and the Comoros and that, in the words of Beaujard (2007:15), constituted a semi-periphery between the nuclei dominant trading countries, Egypt, China, India, and the Middle East and the marginal areas of the interior of East Africa, between the first centuries of the Christian era and the emergence of European trade in the late fifteenth century.

It is from the eighth century when these Bantu inhabitants from the East African coast come into contact with Muslim traders from Oman and the Persian Gulf, discover the secret of the monsoons that allow them to travel from E to W in winter and return in the opposite direction in summer, convert to Islam and go to to be intermediaries between the trade of Asia and Africa, receiving textiles, glass beads and porcelain from the Middle East, India and various parts of Asia and exporting wood, gold and ivory and slaves to these regions.

We have carried out three field campaigns to date. A first of prospecting in 2015 and two excavation campaigns in 2016 and 2017. In 2018, and five days after our departure, alarming news of the violent action of a guerrilla called Al Sabah , with indiscriminate and very bloody attacks on the part of the continent located in front of the Quirimbas archipelago, which caused the arrival of refugees fleeing the attacks to the archipelago, impeded our work. In April 2019, Cyclone Kenneth devastated the Quirimbas, leaving many islanders homeless and without the only hospital that attends to the needs of the archipelago, located on the island of Ibo. That is why we were not able to work in June either, although we did make a twelve-day visit between the end of August and the beginning of September to assess the situation after the cyclone and if the terrorist attacks were under control and we could continue working, which we will do if we get funding for it.

Previous surveys and surveys (Sinclair 1987; Duarte 1993; Stephens (Anonymous 2006; (Madiquida 2007), on the islands of Ibo, Matemo, Quirimba or Quisiva suggested a commercial role not insignificant of the main islands of the archipelago. The Portuguese chronicles themselves describe their arrival in the area in the 16th century as a flourishing textile center in the hands of a Muslim population. The fabric was called Malauane , because the Muslim inhabitants of such a place, located somewhere on the continent opposite the archipelago, would have taken refuge on the island of Matemo as a result of an attack by the Zimba, and, as Newit (1995:189-190) recounts, the Portuguese initially knew the islands under that name. Until the 17th century, cotton and wild silk fabrics obtained from the fruit of the ceiba Pentandra were woven on the islands. . The fabrics were dyed with some local variant of indigo and were highly prized in the Swahili centers of Sofala and the Zambezi River area, in the interior of the mainland. Other versions indicate that the name Malauane of the fabrics derived from the name of the plant with which they were dyed, the "Pano Milwani". Newit (1995:190), also points out the close ties of the Quirimbas Islands with the great Swahili trading ports of Kilwa and Zanzibar.

In short, after the survey carried out in 2015 on the islands of Ibo, Matemo and Quirimba, we decided to focus our efforts from 2016 on Ibo, where the finds on the surface suggested an older occupation.

We have carried out three surveys and an excavation in an area of 18 m². Two of the three probes were successful, although they did not provide habitation structures, which is not uncommon in tropical areas, where humidity and high temperatures work against the preservation of organic structures. However, based on the materials and the dates obtained, we can place the upper levels between the 14th and 18th centuries, due to the presence of small quantities of Portuguese pottery and Chinese porcelain for export, which are associated with indigenous ceramics by hand, type Sancul , characterized by red-slipped plates and graphitized rim, while in the lower levels there are no Chinese or European imports, the indigenous pottery is printed with a wheel or comb and belongs to the Lumbo tradition. , which we can place between the 8th/9th centuries and the 14th century. Three AMS dates on herbivore bone samples from between the end of the 10th century and the 13th century, for these lower levels, as well as the presence of a fragment of pottery glazed on the wheel in survey 100, identified as a Monochrome Yellow Sgraffiato , produced in southern Iran between the mid-11th and 13th centuries (Priestmann 2013:593-594, Plate 99) (Fig.2), would reinforce this chronology.

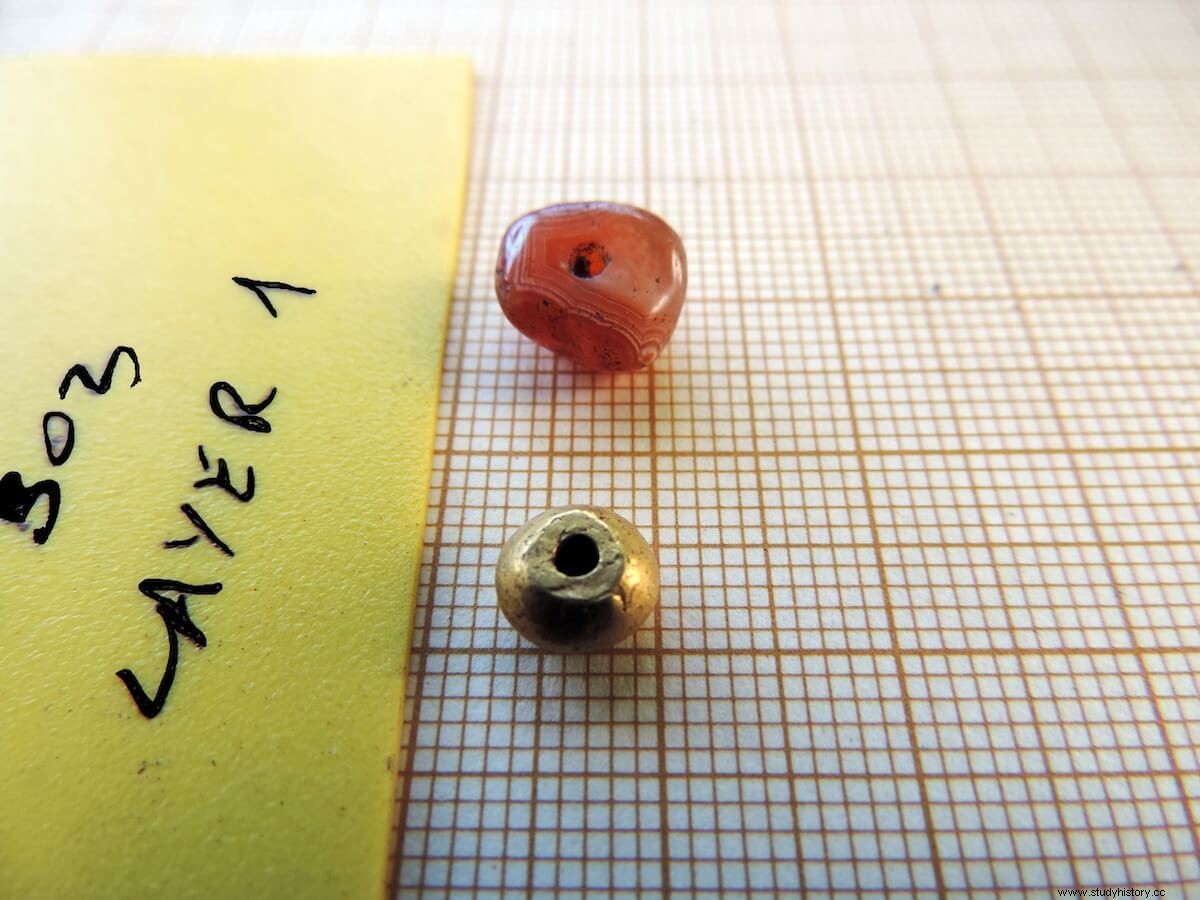

Although we have not been able to detect room structures, we have interesting activities associated with these lower levels in both soundings (100 and 300). Large number of glass beads, possibly imported from the Mesopotamia area and India, along with locally made shell beads (Horton &Midletton 2000:90), from the shell appendage of a local gastropod, the Lambis lambis and to whose finish fragments of ceramic polishers recovered in the same levels are associated (Fig. 3). Necklace accounts played an important role in transactions. Other significant finds are fusayolas, perhaps related to local cotton production for weaving (Newit 2004:24). Even more interesting was the discovery in the lower level of the 300 survey, associated with an AMS dating from the end of the 10th century to the middle of the 12th century, of two necklace beads, clearly imported, one of them made of carnelian and the other of gold.

Although we do not know the origin of the carnelian account, Similar beads are known from other Swahili centers, such as Songo Mnara, where some have shapes similar to ours (Fleisher &La Violette 2013:fig. 17; Perkins et allii 2014:fig.3). Horton (2004:72) considers that carnelian beads could have been an import or else, a local production in the hands of Indian artisans settled in Swahili ports at least since the beginning of the second millennium of our era, due to the complexity of the diamond point drilling technology of these beads.

Regarding the gold account, the analyzes carried out by Dr. Perea, still in progress, indicate that it was a rough piece, which suggests local production from imported gold, possibly from the Limpopo area (northern South Africa). Morphologically and technically it has its best parallels with other gold beads from the Mapungubwe Hill necropolis, south of the Limpopo River, which could be dated to the early 13th century, or from Great Zimbabwe.

It should be remembered that some authors (Newit 1995:23&190-191; Bonate 2012:574), suggest that the 1522 Portuguese attack on Quirimba Island, then capital of the archipelago, It would be justified by the role of intermediary in the gold trade of the Quirimba archipelago, between Great Zimbabwe, the kingdom of Mutapa (N. of Zimbabwe) and the sultanate of Kilwa (Tanzania).

It is possible, then, as Pallaver (2018:450) points out, that beads of exotic origin such as gold or carnelian had a premonetary value for the people of the coast ( Fig. 4) and those of glass and shell will be used for transactions with the interior of the continent.

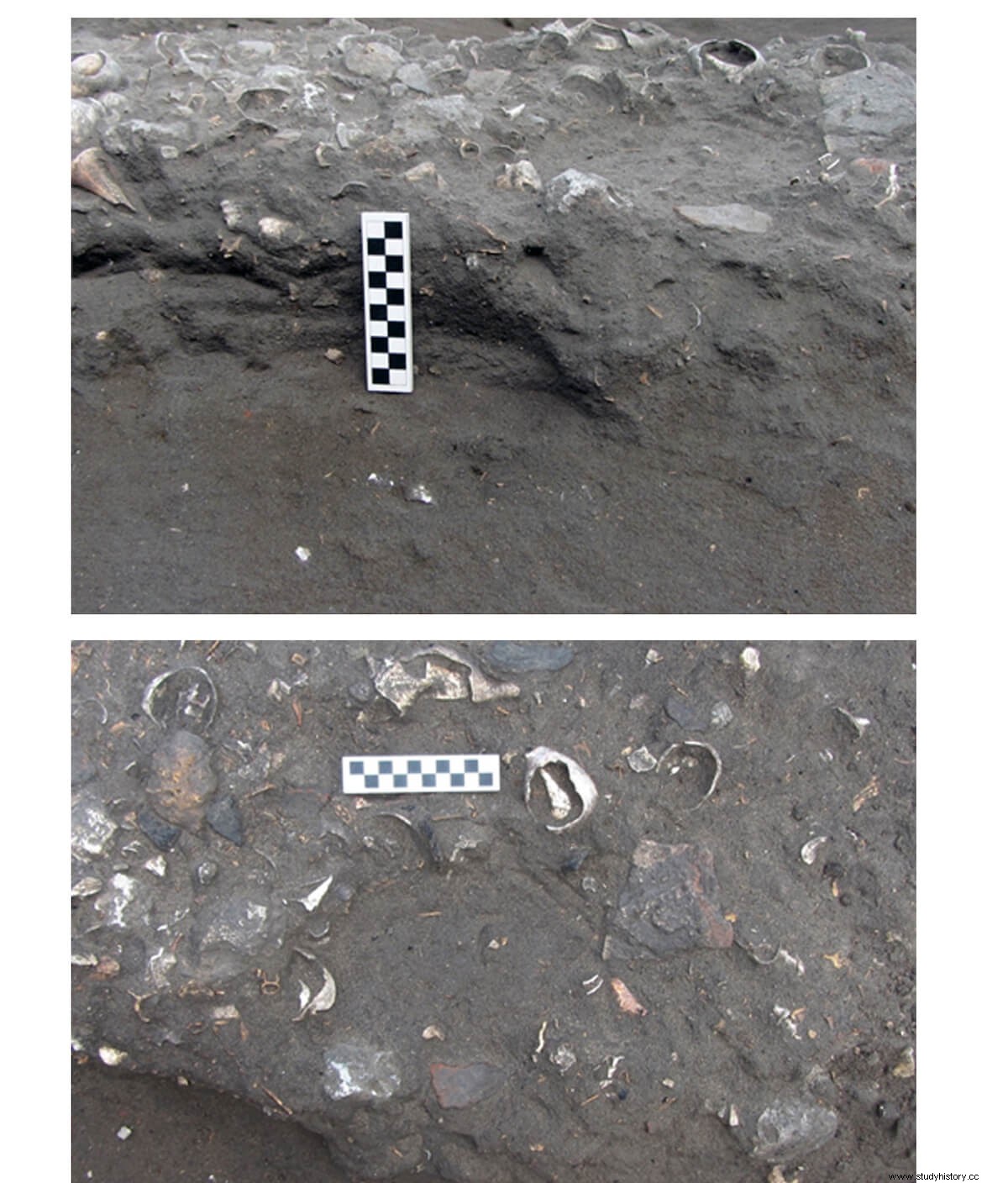

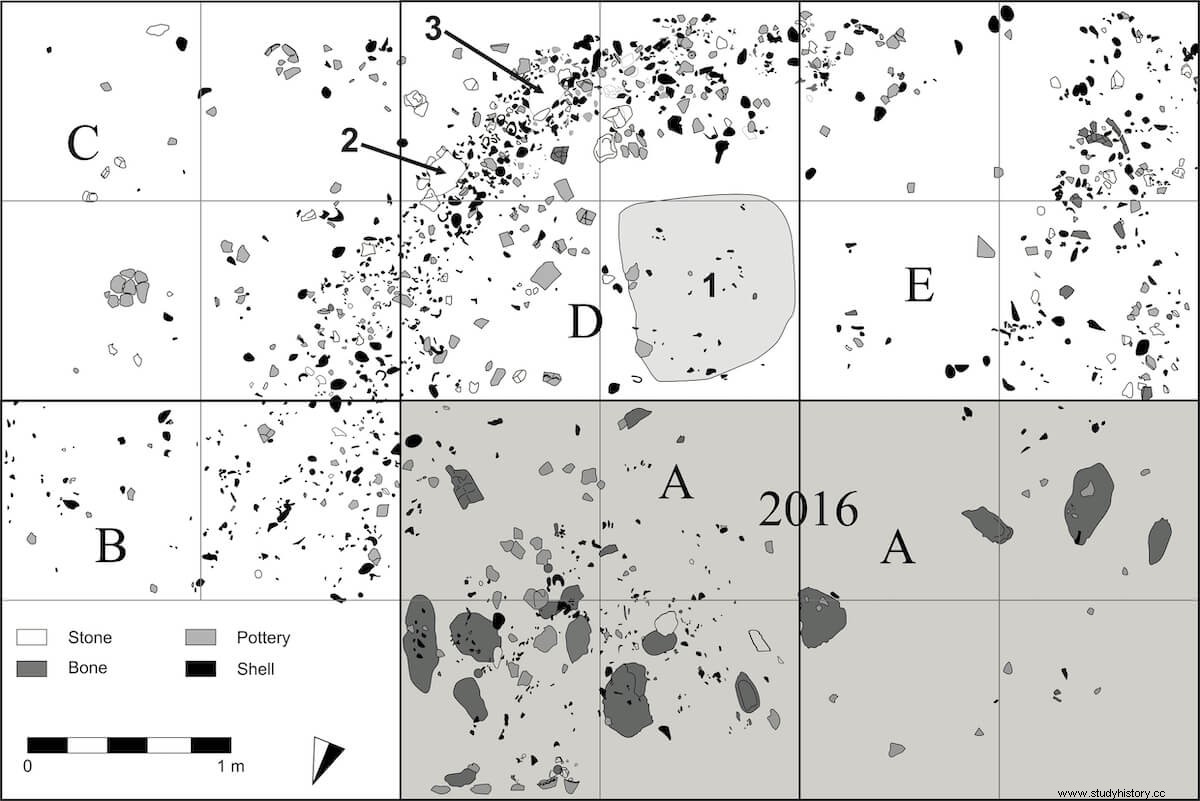

Finally, in the 2016 and 2017 campaigns We have excavated part of a land of Swahili occupation in the area, miraculously preserved, thanks to the fact that the settlement, located near the beach, was partially covered shortly after its abandonment, by a dune run that sealed and preserved part of what we interpret as the floor of a cabin. This interpretation is based on the fact that the excavated occupation floor is delimited by a semicircular structure of about 10-12 cm. high and about half a meter wide in the best preserved parts, formed by a cemented earth dump, fish vertebrae of considerable size, remains of mollusk shells, sea turtle humeri, ceramic fragments, glass beads, fusayolas and even bronze coins. In the SW angle, two circular holes were documented in this foundation structure that we interpret as belonging to posts (Fig. 5).

The most plausible reconstruction, therefore, is that it was a cabin or windbreak made of plant material, which contained and served as a limit to the accumulation of garbage, thrown by its inhabitants to the periphery of the dwelling place. Two other clues came to support our hypothesis. The first is that, outside the area delimited by this semicircle of garbage, the finds decreased exponentially. The second, that, within the space delimited by said semicircle of debris, a rectangular platform appeared, made of compacted earth and reddened by the effect of heat, which we interpreted as a home (Fig. 6).

Among the most significant finds are wheel-glazed pottery and eggshell type (eggshell), from the Persian Gulf and dated between the X-XIII centuries. The paste analyzes carried out by Dr. García Heras of the CSIC (in press), corroborate this origin. Likewise, a large number of glass beads from India and the Mesopotamia area, as well as other local ones made from the shell of the Lambis Lambis (Fig. 7).

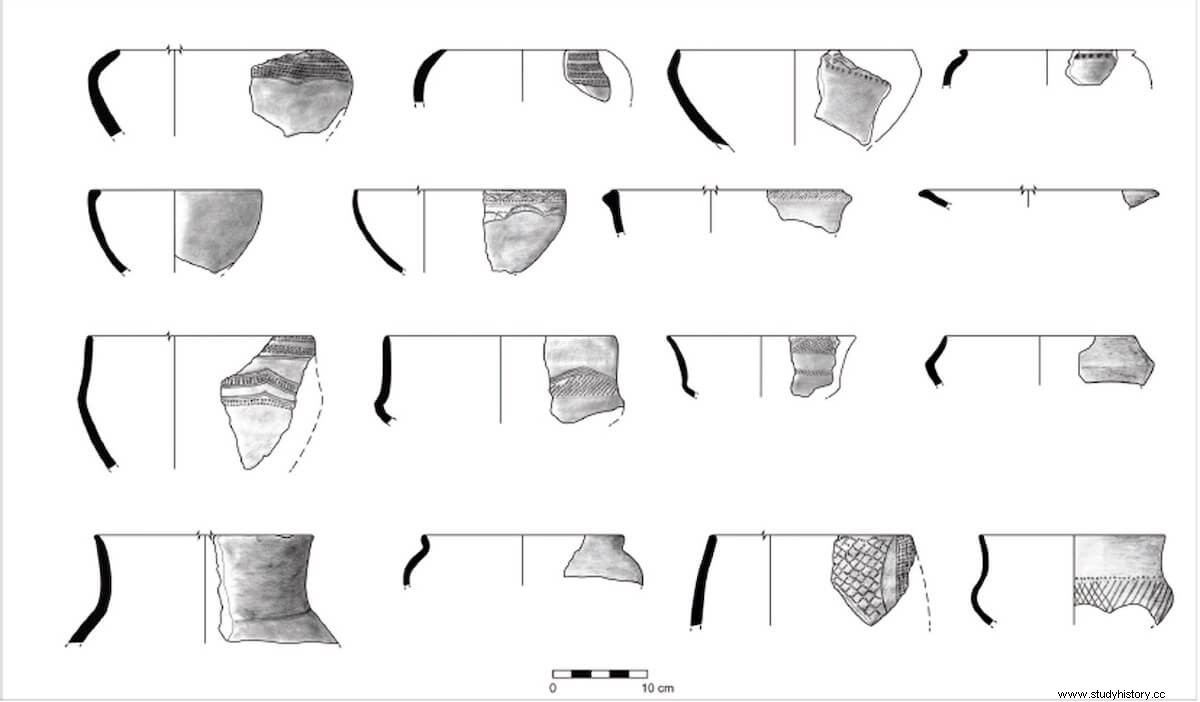

Local pottery (Fig. 8), from which we recovered large fragments, some parts of the same piece, so they were broken in situ, belong to the Lumbo tradition, with globular shapes and comb, shell or wheel decoration.

Very significant is the presence of three small coins of bronze, unfortunately very rutted, so that only one of them can be read an aliphatic sign (Fig. 9). The first East African coins began to be minted in the 9th century, but it was the Kilwa sultanate in Tanzania, with whom the Quirimbas were related, who issued currency for a longer period, that is, between the 11th century and the beginning of the XVI. Unfortunately. Due to their degree of deterioration, Prof. Perkins, a specialist in Swahili numismatists, was unable to identify them. Dr. Ignacio Montero is currently carrying out the Pb isotope analysis of a sample, the results of which are in process, although it can be said that the bronze with which they were made is African.

No less interesting is the recovery of three whole fusayolas and the fragment of a fourth with what we interpret as personal marks. As in the surveys of sites 100 and 300, it reinforces the idea of the development of a local textile industry.

Two tortoise shoulder blade samples dated by AMS using marine curve suggest dates between the late 11th and mid-13th centuries.

Pollen and marine fauna analyzes are also in process, which point to an early attack on the mangrove, fires to clear for livestock purposes and advancement of the open landscape that can be seen from the lower levels of soundings 100 and 300 and reaches its highest levels from the Portuguese domain of the island of Ibo.

Finally, the continuity of this project will depend on our being able to raise sufficient funding to work in conditions in a country and in an area where the scarce and therefore expensive transport, communications and accommodation, represent a serious inconvenience for our research.

Cited Literature

Anonymous (2006):Querimba islands heritage and archaeology. A contribution to Moçambique East African and Indian Ocean world heritage . www.tipmoz.com/library/resources/…/cat3_link_1177665536. Entry 09/02/2016

Beaujard, Ph (2007):East Africa, the Comores Islands and Madagascar before the sixteenth century:on a neglected part of the world system. Azania XLII:15-32.

Bonate, L. J. K (2012):“Six letters in Arabic script from the Mozambique Historical Archives . Tombouctou Manuscripts Project. http://www.tombouctoumanuscripts.org/ Accessed 02/16/2012

Duarte, R. 1993:Northern Mozambique in the Swahili World – an archaeological approach. Studies in African Archeology 4. Uppsala University.

Fleisher, J. &Laviolette, A. (2013):The early Swahili trade village of Tumbe, Pemba Island, Tanzania AD 600-950. Antiquity 87 (38):1151-1168.

Horton, M. (2004):Artisans, communities and commodities:medieval exchanges between northwest India and East Africa. Ars Orientalis 34:62-80.

Horton, M. &Midletton, J. (2000):The Swahili:The social landscape of a mercantile society . Oxford, Blackwell

Madiquida, H. (2007):The Iron-using communities of the Cape Delgado cost from AD 1000 . Studies in Global Archeology 8.Uppsala.

Newit M. (1995) A history of Mozambique . Hurst, London

Newit M. (2004):Mozambique Island:The rise and decline of an East African coastal city, 1500-1700. Portuguese Studies 20:21-37.

Pallaver, K- (2018):Currencies of the Swahili world. In Wynne-Jones, Stephanie &LaViolette, Adria (eds):The Swahiki World . London &New York Routledge:447-457

Perkins, J./Fleisher, J./ Wynne-Jones, S. (2014):A deposit of Kilwa-type coins from Songo Mnara, Tanzania. Azania:Archaeological Research in Africa 49 (1):102-116.

Prietsman, S. (2013):A Quantitative Archaeological Analysis of ceramic Exchange in the Persian Gulf and Western Indian Ocean. AD 400-1275. University of Southhampton. Center for Maritime Archaeology

Sinclair, P. (1987):An archaeological reconnaissance of North Mozambique:Cabo Delgado province. Archaeology and Anthropology Works 3:23-33.

Sinclair, P./Ekblom, A./Wood, M. (2012):Trade and society on the south-east African coast in the later first millennium AD:the case of Chibuene. Ancient 88 (333):723-737.

[1] This project has been funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness HAR2013-48495-C2-2, the Ministry of Culture (IPCE 2016), the Palarq Foundation (2017 and 2018) and aid to research groups (African Archeology Group).