In a not well-known passage from Book II of your Geography , Strabo recounts the eventful story of one of the greatest navigators of Antiquity, Eudoxo de Cícico . By happy chance, Eudoxus, ambassador of his city to the court of Pharaoh Ptolemy VIII Evérgetes (146-117 BC), had come across an Indian castaway there who had taught him how to cross the Arabian Sea between Egypt and the India, a company that had brought him great fame and wealth. And once again providence was responsible for Eudoxus discovering the remains of a shipwreck on the shores of the Red Sea during that fortunate voyage. From the shipwreck of what the seasoned sailor identified as an old ship from Cadiz. The size of the find spurred Eudoxus' ambition. Therefore, he soon left the pharaoh's court, returned to his land, invested all his fortune and traveled to Gadir. His objective was none other than to visit India again, but this time by circumnavigating Africa, an undertaking for which he hoped to count on the help of the people of Cadiz, who, judging by the shipwreck that Eudoxus had discovered on the shores of the Red Sea, already they had at some point in the past. At Gadir he chartered a large merchant ship and two auxiliary boats, and, together with the crew of the three ships, he recruited several doctors, craftsmen of various kinds, and a group of young musicians. And, with the help of all of them, he went to sea (Strabo 2.3.4).

After a few more adventures along the Mauritanian coast, Eudoxus' fate is lost in the mists of history. We don't know what happened to him. But, if in these lines I have brought up this suggestive passage, it is because of the unique reference made in it to young female musicians from Cádiz. Who were these women, and why did Eudoxus bring them aboard? Incredible as it may seem, this question does not seem to have aroused the curiosity of historiography. No, at least, since A. García y Bellido first and J.M. Blázquez later identified these mysterious women with the puellae gaditanae , the exotic dancers with sensual swaggers that, apparently, delighted the young Roman aristocrats in the times of Martial, Juvenal, Statius and Pliny. But, if for a second we stop lying about the matter, do we really think it likely that an experienced sailor like Eudoxo embarked some "dancers" of this type for his exploratory expedition? To what extent can we identify as puellae gaditanae to these young musicians (they were not "dancers", but "musicians", according to Strabo:μουσικὰ παισισκὰρια) who boarded Eudoxus' ships more than a century before Roman authors began to mention the arrival in Rome of exotic dancers Cadiz? Isn't this identification based on our own prejudices about the role of women in the ancient world?

Young Iberian musicians

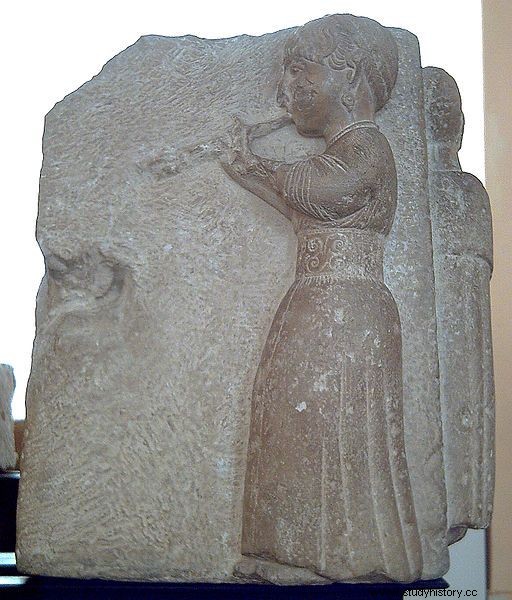

To answer these questions, I propose a journey through the images of his “young musicians ” the Hispanic peoples themselves bequeathed to us. Surely the best known, and also the closest to the Cadiz port, is the one represented in one of the Osuna reliefs that are preserved in the National Archaeological Museum. We are talking about some ashlars that were reused next to a wall from the Caesarian period, but that would belong to an Iberian monument erected on the outskirts of the settlement between the middle of the 3rd century and the end of the 2nd century BC. C. Well, among all these reliefs, which tell us about horsemen, single combats and processions, we find a young musician represented. A woman plays the double flute, her cheeks swollen and her eyes focused on the instrument. She wears a long tunic whose sleeves have been rolled up so that they do not hinder her movements, and she wears a wide belt with colorful ornaments that among the Iberians used to be more typical of warriors than women, and that in this case does not make the character stand out. She is further adorned with eye-catching earrings, and her curly hair is gathered into a braid that has been coiled over her crown. Her belt, braid and absence of a cloak leave no room for doubt:according to Iberian canons, she is not an adult, married woman, but a young woman. A young musician who plays her flute among all the plethora of warriors and parades that adorned the monument.

Also from between the end of the third century and the first half of the II a. C. date from a whole series of ceramics modeled in different Valencian, Alicante and Murcia potteries among whose decorations we find, again and again, the usual young musicians. They appear, for example, in Sant Miquel de Llíria, where, in the so-called “vessel of ritual combat ”, a young flutist and a man who plays the tuba flank two warriors locked in single combat. Surely these are two legendary, paradigmatic champions, whose battle takes place in a liminal setting populated by flowers, rosettes, and vegetable scrolls of all kinds. We know nothing else about the tuba player, since he is the only character on the glass whose clothing has been depicted as opaque, without any attribute that allows him to discriminate his function or social status. The flutist, on the other hand, is young (her braids betray her age), and over her miter and tunic she wears an ostentatious translucent veil that announces her distinguished social position. The same thing happens in some other vases of this same city, capital of Edetania, an ally of Rome during the Second Punic War and destroyed by it a few decades later, perhaps as a result of some kind of uprising:the various flutists that appear are always young, show ostentatious clothing (the miter and the translucent veil along with the braids, in fact, appear over and over again, revealing a pattern), and accompany with their music singular combats that take place in liminal, legendary scenarios, or guide with its rhythm the parades and the festivities of the community.

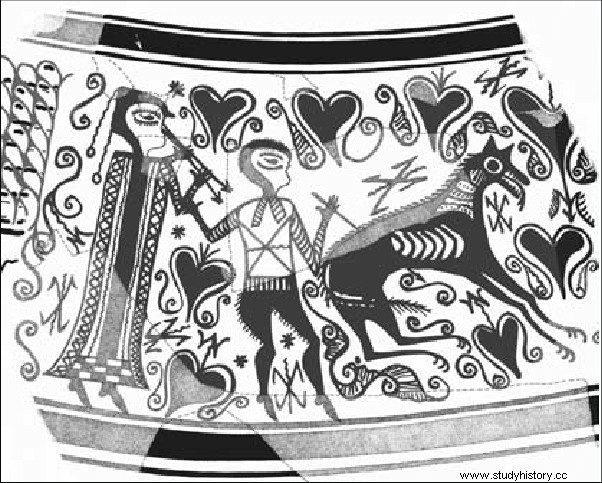

Identical flutists are, in fact, depicted in other contemporary Levantine habitats. In the so-called "glass of warriors ” de la Serreta d'Alcoi unfolds what R. Olmos and I. Grau interpreted as the successive episodes of the biography of the local hero:a hero who, while still little more than a child, killed a gigantic wolf that threatened to the community; that, already young, he participated in the vertiginous hunt of a divine deer; and whose culminating moment came when he had to face his most fearsome adversary alone:another (anti) hero who, dressed like him and armed like him, dared to threaten his power. Well, let's pay attention, once again, to the fact that a young flutist, combed and dressed like those of Sant Miquel de Llíria, rhythms the various scenes of the myth with her music.

Among the Levantine Iberian communities of the late third century and from the 2nd century BC. C., therefore, the representation of young female flutists is recurrent, always linked to mythical episodes or parades . Historiography has hardly paid attention to them, assuming that with their music they would only accompany the civic processions of the city and the ritual combats. The protagonists of the different scenes were others, men, and they constituted only the troupe. But the detailed study of all these images leads me to reconsider this interpretation. What was the real function of this character that is so habitually represented in Levantine Iberian ceramics, always embodied in a young woman of high social status, and who is often dressed in the same clothes, as if she were starring in some kind of ritual act? Was it just the musical accompaniment of the heroes and dancers? Let us remember the “vase of the warriors” of the Serreta d'Alcoi to which I alluded before:was it really represented as a young musician who, without taking the double flute from her lips, accompanied the child hero in his pursuit of the monstrous wolf in the most intricate of the forest? Couldn't it be that we were talking about something very different?

Repositories of memory

It is possible that a passage from Sallust could help us clarify the dilemma. Writing about Sertorius's war in the Iberian Peninsula just a few years after the events, the Roman historian maintained that "it was typical of Hispanics that, when young men marched into battle, their mothers reminded them of their fathers' deeds" ( Health, Hist . 2.92. Trad. of M. A. Rodriguez Horrillo). Although there is no consensus on this among historians, it is very possible that with this comment Sallust was referring roughly to the Celtiberians, and not properly to other Hispanic peoples such as the Iberians. It is also true that the Roman historian specified that it was the mothers who remembered (memorarentur matribus ) the deeds of the ancestors :I wasn't talking about young people, but about mothers . But, despite everything, I consider that this quote is extremely suggestive when reflecting on our little dilemma about young Hispanic musicians. At least among the Celtiberian communities that participated in the Sertorian wars, it was the women who remembered and transmitted the deeds of their ancestors to the next generation, and they did so with music, singing. A century later, in fact, the archives of the Celtiberian city of Clunia would recall that in pre-Roman times the gods had spoken through a girl (a girl, not an adult woman:fateful puella ) to prophesy the advent of the emperor Galba (Suet., Galba 9.2). Well, in the Levantine Iberian world of the 2nd century BC. C., could it not be the young women of aristocratic families (or perhaps certain youth of certain aristocratic families) those in charge of remembering and transmitting with their music the deeds of the ancestors, the myths, the memory, in short, of the community?

Let's go back to the example mentioned above, to the “vase of the warriors” of the Serreta d'Alcoi. In my opinion, the young flutist did not accompany in his mad race through the forest the boy who was chasing the monstrous wolf, nor did she ride at full speed with the horsemen who harassed the divine deer that they would eventually hunt down. She just evoked, with the notes of her flute, the legendary story of the local hero, ruled by all these episodes. The flutists of Sant Miquel de Llíria and other Levantine potters from the end of the 3rd century and the 2nd century BC did the same. C.:they recalled through music the mythical deeds of the ancestors, and accompanied the community festivals with these sounds. What's more, let's look at the double flute of the young music of La Serreta, represented with an unusual detail in no other representation:the ends of the two pipes of the instrument are finished off in wolf heads. Hers is a unique flute, that of a young woman destined to commemorate the legend of the local hero for the community.

In the Serreta d'Alcoi itself, another representation of a flutist appeared that possibly helps us to delve a little deeper into the approach. The room in which the aforementioned “vase of the warriors” was found also contained a terracotta plaque in which the local divinity was represented. In the center of it, and standing out for its great height (an extraordinary height, so excessive that it exceeded the frame of the terracotta plate, as befits a divinity), a goddess held two children against her breasts, nursing them. She is a nurturing goddess, typical in these Levantine urban environments of the end of the 3rd century BC. C. To her right, and represented at a much smaller size (consistent, after all, with her human condition), a woman approaches the goddess together with her son. She rests her right hand on the boy's shoulder in a protective gesture, but she reaches out with her left towards the divinity, whose mantle she reverently brushes. We find ourselves before an epiphanic scene , in which the goddess suddenly appears before certain mortals, allowing them, a mother along with her son, to approach her to worship her. The closeness of the deity purifies, sublimates the human being, and without a doubt the mother, with her pious gesture, is instructing her offspring with her example in this whole system of values. But let us observe what is on the other side of the scene, to the left of the goddess:a musical woman plays the double flute, accompanied in her tune by a small flutist (the schematism of the terracotta makes it impossible to know his sex) who tries to to imitate the first As if it were a game of mirrors, just as the woman on the right of the goddess teaches her son how to approach the goddess, the woman on the left indoctrinates her pupil in the sound of the flute. Does she teach him, perhaps, to evoke with her music the memorable, paradigmatic moment in which the goddess appeared to mortals, at some point in the past? I see it very possible.

Let us finally attend to the Iberian funerary record of these same years. At the foot of the Alcoy mountains, to the north of the current city of Alicante, lies the Albufereta necropolis (Alicante), a cemetery in which some four hundred tombs have been discovered. Among them, tomb F42 draws our attention, dated with some precision at the end of the 3rd century BC. C. Inside, the mandatory cremated human remains rested together with several cups of black varnish, an ointment dish, a jewel of vitreous paste, a spear point, a whole batch of fusayolas (ceramic pieces to tense the fibers during the process yarn) and a terracotta depicting a young musician playing the double flute. We find ourselves, it seems, before the grave of a woman of high status, who had herself buried along with all those objects that could guarantee her a better existence in the Hereafter and who, at the same time, responded, or tried to respond, to the place that the deceased had occupied in life in her society. It is no coincidence, then, that the only image of all the grave goods was the terracotta of a flutist. In the same way that this woman would assume that her role in society was reflected in the ointment dish, in the vitreous paste jewel, in the cups or in the fusayolas, she would also see herself represented, I think, in the figuration of this flutist .

The same could be proposed, in fact, for the monument of Horta Major, whose vestiges were found during the construction of the Retiro Obrero building in Alcoi (Alicante), at the foot of the mountain of the Serreta. We are talking about a set of ashlars dated, approximately, at the end of the 3rd century BC. C., and decorated with reliefs that, judging by the scenes represented, could originally have been part of a funerary monument . In them appear two mature women covered with veils and cloaks and adorned with showy earrings, crying and tearing their hair, and two other females who have been represented recumbent, surely lifeless. Quite possibly it is the deceased in whose honor the monument was erected, which indicates unequivocally that they would be privileged women, belonging to the cream of the local aristocracy. Both are covered with a pleated tunic, mantle and veil, and both wear ostentatious diadems, showy earrings (like those of the Lady of Elche) and several superimposed necklaces. But one of the two is distinguished from the other by a curious detail:in her left hand, resting lifelessly on her belly, she still holds, as the only differentiating element, a double flute. Apparently, this woman (or perhaps the living relatives of the female who orchestrated her burial) wanted to distinguish herself from her fellow citizens by her relationship with the double flute. He believed it was essential that that object appear in her funerary monument as something linked to her identity, to her memory. This aristocrat wanted her to be remembered as a flutist.

It seems clear to me that the female musician in whose honor the funerary monument of Horta Major was erected, or that other woman who was buried in tomb F42 in Albufereta, were more than just mere flutists who accompanied the festivals and rituals of their respective communities with their sones. And the same can be said of the women musicians represented in the ceramics of Sant Miquel de Llíria or Serreta d'Alcoi, among many other Levantine settlements. We are talking, in all probability, of young aristocrats belonging to the most distinguished families of their societies, responsible for learning, preserving and transmitting (and, if necessary, asserting before their countrymen in need of encouragement, as Salustio commented during the Sertorian wars) the memory of the community. Those deeds of the ancestors that had to be evoked generation after generation, and whose memory served to unite the group. Some deeds that, apparently, both among the Iberian and Celtiberian communities, were transmitted with songs, to the rhythm, perhaps, of the flute.

The experienced navigator Eudox of Cyzicus may not have been looking for anything else when he landed in Gades, eager to prepare the daring expedition with which he hoped to circumnavigate Africa. He needed ships, sailors, carpenters and doctors, no doubt, but he also needed someone to remember how, in a long-forgotten past, some Cadiz man had managed to reach the Red Sea with his ships. And for this reason he managed to be accompanied by the only people who, in the port of Gadir, remembered the deeds of the ancient Phoenician navigators. To this end, he embarked those young musicians, who, as much as it may surprise us modern historians, were much more than exotic dancers recruited for the solace of the crew.

Bibliography

- Cunliffe, B. (2019):Ocean. A history of connectivity between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic from Prehistory to the 16th century . Madrid:Wake up Ferro.

- García Cardiel, J. (2016):The discourses of power in the southeastern Iberian world (7th-1st centuries BC) . Madrid:CSIC.

- Sánchez, M. (ed.) (2005):Archeology and gender . Granada:University of Granada.

- Tortosa, T. and Santos, J.A. (eds.) (2003):Archaeology and iconography:digging into images . Rome:L'Erma di Bretschneider.

- VV.AA. (2015):Archeology and History No. 1:Iberian culture . Wake up Ferro Editions.