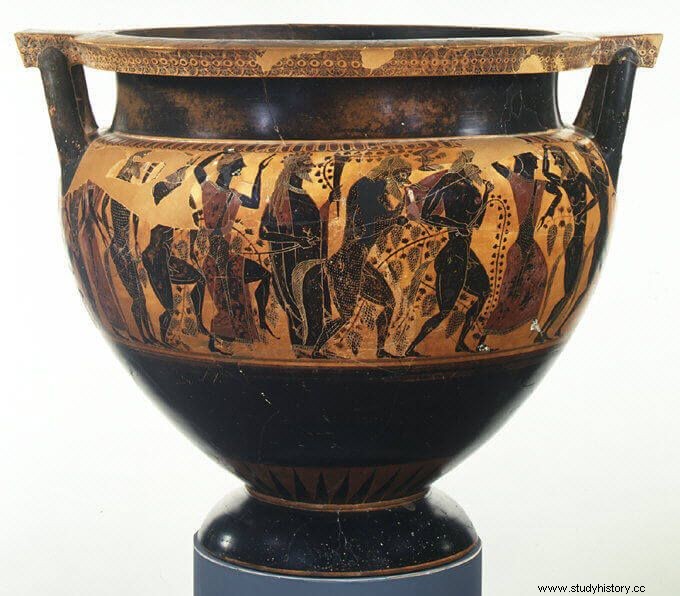

In March, according to Ovid, the feast of Bacchus , identified with the Roman Liber, the god of wine and vines. He was also identified with the Dionysus Greek, a very local god, but with an oriental appearance, surrounded by satyrs and maenads, in his chariot pulled by tigers and panthers. He was a fearsome and kind god at the same time. A god who, when captured by pirates, filled the ship with panthers, bears, vines and nature, but who took pity on the sailors who fell into the water and turned them into dolphins. A god capable of making the women of Pentheus's family tear him apart, believing him to be a lion, in full mystical ecstasy, for offending him and opposing his cult. A god capable of the best and the worst, of mystical madness, of dance, of music. A very human god, like the Greek gods.

In Rome, also related to wine and its mythical sphere, the Vinalia were held in April and August. , also dedicated to Venus and with the participation of prostitutes and dancers. Wine, love, fertility and vegetation were mixed in a very popular festival. In Greece there are also numerous festivals related to the wine cycle. One of the best known is the festival of the Antesterias , at the end of February or the beginning of March, when the new wines were opened (and people drank in huge quantities), there was dancing and comedies. The rustic and urban Dionysias were also celebrated (in December and March) and the Leneas .

A particularly bloody episode related to the celebration of this god (or these gods, rather) happened in 186 BC. in Rome. In that year the Romans decided to suppress the bacchanals , which had become nocturnal rites in which not only women participated, but also young people were initiated. The Senate called it a full-fledged conspiracy, accusing women of committing obscenities, child rape, murder, and whatever else crossed their minds. The repression ended, according to the sources, with thousands of deaths, between men and women, and the prohibition of these mystery rites.

The importance of wine in the classical world

But why so many honors, so many parties, so many rites around Dionysus, Bacchus or Liber? Keep in mind that wine has been a fundamental element in the basic diet since prehistory in the Mediterranean area. Knowledge of vine cultivation goes back in some places as early as the Neolithic, and the pharaohs of the First Dynasty already produced their own wine. Homer tells us about a sea the color of wine, that “wine point” −analyzing how vocabulary related to colors arises and why they did not know blue would be for another article−. In fact, along with oil and cereals, wine has become part of a mythologized triad, it has been part of art, literature and the collective imagination until it reaches our days as an important part of our diet, leisure and social life.

Wine, along with beer and mead, are both safe ways to consume fluids and to preserve food. But also the alcoholic content was basic in many religious ceremonies and festivals that involved commensality. It was a fundamental element in banquets, which fulfilled a basic social task, associating itself with pleasure, sociability and celebrations. Banquets and symposiums served as elements of socialization, not only among the elite, to strengthen their ties, but also at times such as births and weddings, when the community needed to recognize and remember the moment. In a world without civil registries, it could be vitally important for your neighbor to remember that he was indeed at your introduction as a new member of the family, or that your wedding was legitimate.

Depriving someone of wine was considered an important punishment, showing the austerity and harshness of life to which someone could be condemned. When Augustus confined Julia to a small island, she was banned from wine, along with human contact and other comforts. The same happens with the penances to “bread and water”. On the other hand, its free distribution in shows and special occasions, was something that the Romans especially appreciated. Marcial says, for example, that in his time bonuses were distributed to spectators for ten glasses of wine. Although Pliny said that in ancient times Roman women were not allowed to drink wine, he does so only as a poetic exaggeration. In fact, just before she mentions that Livia attributed her longevity and good health to Pucino's wine, which she drank daily.

Types of broth

There was not just one wine, but different qualities were recognized and different grapes (ammineas, nomentanas, apianas...), in addition to distinguishing, both Greeks and Romans, white from red wine. They also distinguished between sweet and dry wines. In addition to the aforementioned Pucino wine, the one from Falerno was among the most renowned, along with the Masico. Although of course, Roman authors always tried to extol Italian wines over those from other areas. The wine from the interior of Africa, on the other hand, would be very bad, and the one from the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula weak and of little graduation, like that from the Vatican field. Dioscorides also disowned new wine in general, since he considered it indigestible and the cause of nightmares.

There were also other variants that were out of the normal way of production. For example, the passum It was the wine that was made from raisins. In the East, wine was not only made with grapes, but also with dates or even with the sugary resin of the date palm crown, giving rise to what the Romans called "palm wine".

In any case, the wine was much more acidic than the current one, since it was not produced in wooden barrels (which only began to be used in the Late Empire), but in large pithoi ceramics, and can also be stored in skins waterproofed with pitch. It was also moved and stored in amphorae, which would alter its flavor over time. Even today, and especially in rural areas of Extremadura and nearby regions, the so-called "pitarra wine" is still being made, with a slightly higher alcohol content than usual and produced in ceramic containers. In any case, if the wine ended up becoming too vinegary, there was always the possibility of making the so-called posca , a drink made with the resulting vinegar, water and various aromatic herbs. It was very common in the army and was what was offered to Jesus on the cross, according to sources.

The acidity was solved by mixing the wine with water , in a variable proportion, which also made it possible to drink more and for a longer time. In addition, different additives were added, especially honey . The mulsum is frequently cited , but also the oenomelli , with more honey than wine. The oxymel , on the other hand, would be a variant of mead, to which vinegar was added. Spices were also added, some of them psychoactive, such as saffron. In addition, they drank, on many occasions, and especially in winter, mulled wine , like the current mulled wine English.

Wine was also a basic element in medicine , either alone or as a base for various remedies. This would last in Islamic times as an exception to the prohibition of drinking alcohol. Thus, lettuce seed dissolved in wine prevented "libidinous dreams" according to Pliny, and laudanum, the main painkiller and strong analgesic of the time, was made with wine, opium and saffron. Also medicinal wines that were made with elements other than the vine, or to which different plants were added during or after fermentation. Plinio speaks, for example, of escamonea wine, which causes abortion.

Everything with measure

Of course, the authors already recommend moderation in the consumption of wine. Eubulus claimed that:

It seemed clear, then, that excessive consumption of wine, and even more so when it was mixed with psychoactive substances , had certain unintended consequences. Even so, it would be necessary to see what the Romans considered excessive, since, for example, speaking of Alexander Severus and praising his moderation with wine, they said that he only had for his daily consumption four sextaries of wine with honey and another two of honey with pepper Taking into account that a sextary is more than half a liter, consumption is, in our eyes, a little high.

One of the consequences was excessive disinhibition at the time of consumption. The Greeks and Romans already said that the truth was found in wine:in vino veritas . When, according to Herodotus, the grandfather of the Athenian Cleisthenes, of the same name, intended to marry his daughter and had chosen Hippoclides, he danced, encouraged by the wine, in a rather immodest way. Cleisthenes annulled the wedding while he reproached her for his attitude. He only replied that "Hippoclides doesn't care", which became a popular saying. Alcibiades also ends up scolding Socrates, at the end of the Banquet , due to his lack of sexual activity, saying, moreover, that children and drunks tell the truth. Aggressiveness was also part of that disinhibition. The centauromachy represented, among many other supports, in the Parthenon of Athens, reflects another problematic moment for wine, the one in which the centaurs, invited to a wedding and drunk as a bucket, decided to kidnap the women of the Lapiths, unleashing a battle campaign that ended with the expulsion of the centaurs from Thessaly.

Perhaps the most surreal anecdote was narrated by Athenaeus, and tells how some young people went too far with the wine to the point of thinking that, instead of the banquet, they were in a boat. Excessive seasickness made them think they were shipwrecked, so they decided to lighten the "load" by throwing the furniture into the street. After plundering the neighbors as much as they wanted, they called a magistrate, who desisted from retaliating when one of the young people, one of the most serious, complained that he had not done anything... he had only stayed under the benches of the boat because he had fear.

Thus, it is not uncommon for wine to be associated to the lack of control , especially in the case of pure wine. Drinking it unmixed was considered typical of barbarians, both in Greece and Rome, or excessive. Aristophanes relates it in women to another vice, that of hiding their lovers in their own homes. Even so, on some important occasions, such as the celebration of a birth, the wine would be drunk slightly mixed, especially to encourage the attendees. In fact, the Greeks even created a specific position, that of the oinoptai , to control public spending on wine at festivals and other issues arising from its excessive consumption.

The second main and unwanted consequence of these excesses was a hangover. In fact, the entire beginning of the Banquet of Plato consists of the excuses that young and old give to drink "at pleasure" and not according to the order established by the host, given the accumulated hangover of the previous days. No one wants to appear weak or a spoilsport in front of the rest, but they cannot with their soul. Pliny also complains about Pompeian wines, stating that the hangover they leave is not only bad, but long-lasting. The "death of memory", stinky breath and headache are immediate effects, but he also describes consequences of alcoholism long-term, such as hand tremors, eye spills, or paleness. It seems that the Romans were especially aware of the unpleasant smell and taste of breath, so they invented pills and perfumes to avoid it, a kind of precedent for our menthol candies.

In fact, both the Greeks and Romans, as well as the Egyptians before them, attempted to invent, collect and pass on hangover remedies . Boiled cabbage, bitter almonds, vomiting or taking a bath appear as possible remedies… although, like today, the only real remedy would be time and rest. And swear that one is older for these things, until the following Anthesteria.

Bibliography

- Dalby, A. (2003):Food in the Ancient World, from A to Z . London:Routledge.

- Gately, I (2008):Drink:A Cultural History of Alcohol. London:Penguin

- Phillips, R. (2001):A Short History of Wine . London:Penguin.

- Notario, F. (2011):“Delicacies of cradle and bed:the sacrificial banquets for births and nuptials in the Athenian democracy of the fourth century BC.”, Arys:Antiquity :religions and societies , 9, p. 67-83