Not only does it contain the longest known text in the Etruscan language, it is also considered the only existing ancient book written on linen.

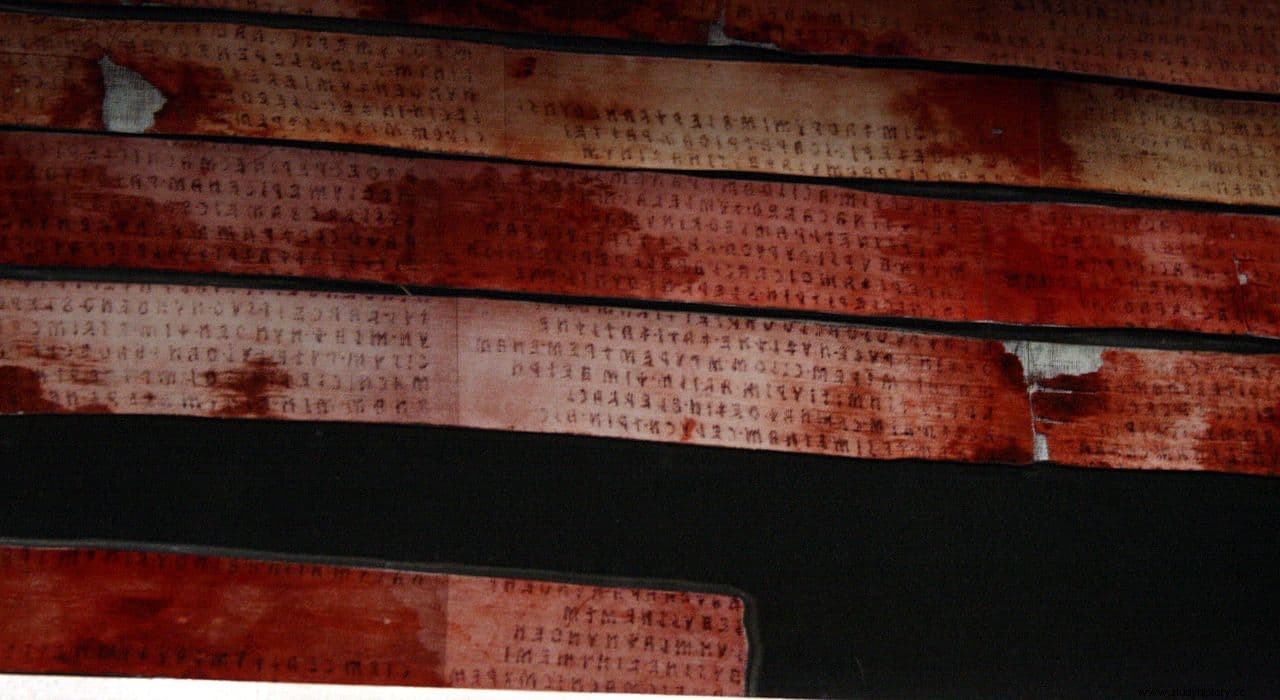

It is known as Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis (the linen book of Zagreb) and also as Liber Agramensis . It contains the only extant non-epigraphic Etruscan text , which is distributed in 230 lines that total about 13,000 words, of which only about 1,200 are legible today.

This is due to its poor state of preservation, since when it was discovered in the mid-19th century, the linen fabrics on which it is inscribed had been torn and used to bandage a woman's mummy in Egypt.

Interestingly, the document has been radiocarbon dated to around 250 B.C. and the mummy dates to the same time, just a few years later, raising questions about how the text got there. Whether the book was created in Etruria and then taken to the other side of the Mediterranean, or whether it was written in Egypt remains a mystery.

Linen was cultivated preferably in Egypt for several centuries, but we must not forget that linen cloths have also been found in ancient deposits in Central Europe. In any casethe latest theories suggest that the book was written in Egypt , probably by an upper-class Etruscan.

The mummy was bought in Alexandria in 1848 by Mihajlo Baric, a Croatian official from the Hungarian Royal Chancellery who had left his post a few months earlier to travel the world. While he was in Egypt he acquired as a souvenir a sarcophagus containing the mummy of a woman, which was taken to her house in Vienna where it was displayed in a corner of the room until her death in 1859.

Sometime between his return to Vienna and 1859 he removed the linen wrappings from the mummy, and placed them in a glass case, unaware of the significance of the inscriptions they contained.

Both the sarcophagus, the mummy and the bandages were inherited by his brother Ilija, a priest who lived in Slavonia (in present-day Croatia). His lack of interest in such objects led him to donate them in 1867 to the predecessor institution of the Zagreb Archaeological Museum, which is where they are preserved and exhibited today.

That same year, 1867, the German Egyptologist Heinrich Karl Brugsch visited the institution, who only three years later would become the director of the Cairo School of Egyptology and his work would be key in the decipherment of the demotic script. /p>

Brugsch saw the texts inscribed on the linen, but thought they were Egyptian hieroglyphs and didn't have time to study them more closely. Ten years later while talking to the famous explorer Richard Burton about runes he suddenly remembered what he had seen in Zagreb and realized that they were not hieroglyphics.

Instead he thought that it must be Arabic script, and the text a transliteration of the Book of the Dead Egyptian. He once again he was wrong.

In 1891 the bandages were transferred back to Vienna so that they could be studied by Jacob Krall, the greatest expert on the Coptic language of the time. It was he who identified the texts as Etruscan and carried out a reconstruction by ordering and joining the linen fabrics.

By the mention of some local gods in the text of the manuscript, it has been possible to determine the origin (either of the text or of its creator) to a small area in the southeast of Tuscany, between the cities of Arezzo, Perugia, Chiusi and Cortona.

It consists of 12 columns, each one representing a page, the first three seriously damaged and illegible, so it is unknown how and where the text begins. It is inscribed in black ink for the main text, and red for lines and diacritics, and was originally meant to be folded like a codex, rather than rolled.

Because the Etruscan language has not been completely deciphered, only a few words can be read, such as the names of the gods and dates, which makes experts think that it may be a kind of religious liturgical calendar that marks the rituals for each day of the year, the famous and lost Etruscan discipline mentioned in Roman sources.

Some authors, such as Sergei Rjabchikov, relate it to astronomy due to the appearance of names of constellations and other celestial bodies that, in their opinion, are astronomical records derived from observations in order to predict the weather and other events. He even claims to have identified the record of a solar eclipse that happened on February 11, 217 BC. This eclipse was barely visible from the Italian peninsula, but it was visible from Alexandria. Which fits with the theory that the book was written in Egypt by an Etruscan priest who immigrated there in the context of the Second Punic War (which started in 218 BC).

As for the mummy, which was restored by specialists from the Vatican Museums in 1998, today it is exhibited in a special refrigerated chamber of the Zagreb museum. It is known from the papyrus that accompanied her that she was Egyptian (at some point Krall came to think that she could have some relationship with the Etruscans). She was called Nesi-hensu and was the wife of Paher-hensu, a tailor from Thebes who made clothes for the statues of Amun.

Fonts

Archaeological Museum of Zagreb / Profesionalescroatas.cl / The Etruscan World (Jean Macintosh Turfa, ed.) / Etruscan Astronomy (Sergei Rjabchikov) / Wikipedia / Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis. The Linen Book of Zagreb:A Comment on the Longest Etruscan Text (L. B. Van Der Meer )