The cave paintings of the European caves of Lascaux and Altamira are among the most impressive in the world. But they are not the oldest, nor are they the most prolific.

If we stick to antiquity, we must consider those discovered three years ago on the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia, which would date back to about 40,000 years ago. The archaeologists then highlighted the surprising stylistic similarity of these paintings with those of the caves of northern Spain and southern France.

And if we look at the quantity, the palm would go to the Brandberg mountain in Namibia, which is home to some 45,000 cave paintings although from a much later time, some 2,000 years old.

A place that combines both aspects is also in Africa, in an unexpected area due to its aridity, in the part of the Kalahari desert that belongs to Botswana.

It is Tsodilo, four isolated hills, the largest of which rises 1,400 meters above sea level (400 meters above the surrounding area), which in its 10 square kilometers of surface house some 4,500 cave paintings, the oldest dating back almost 24,000 years old (those of Lascaux and Altamira have been dated to 17,000 years ago).

In the hills, they are called Macho , Female (the tallest), and Child (the fourth mound is unnamed), there are numerous caves in which prehistoric artifacts dating back 70,000 years have been found, as well as at least 20 prehistoric mines. That, together with the paintings, has earned the place inclusion in the list of World Heritage Sites by UNESCO, who on its official website considers it one of the largest concentrations of parietal art in the world, and calls it the Louvre of the desert , adding that:

Most of the paintings are found on the Female hill , being the panel Laurens van der Post the most famous set of all, named after the South African writer of the same name who first described them in his book The Lost World of the Kalahari , published in 1958.

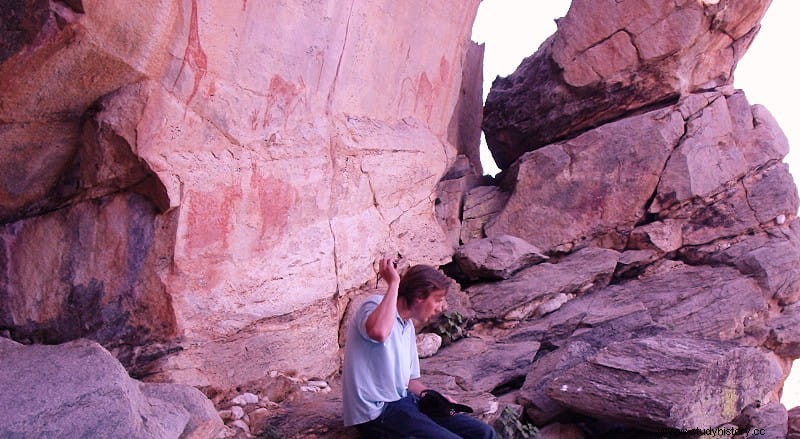

Although rediscovered for the Western world in 1898, the paintings did not receive legal protection until the late 1930s. And study of them would not begin until 1978, when the Botswana National Museum began cataloging them, along with excavations of the numerous caves and mines.

Today there is a small museum and a camping area with showers and services for visitors who come to the place, with the possibility of hiring guides to take a tour of the most outstanding paintings (most of the 500 areas with paintings are in places difficult to access).

What made these hills so special? It is a question that researchers have been asking for decades, especially considering that no other hill in the area shows paintings or traces of occupation. The answer probably lies in its consideration as a sacred place, the place of birth and death of the first gods of the local peoples.

Experts estimate that the hills were used ritually by hunter-gatherer peoples for thousands of years. Some of the paintings, the more than 3,800 of which are red, would have been created by the ancestors of the San people (Bushmen), today reduced to just 95,000 individuals spread across Botswana, Namibia, Angola, the Republic of South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Others, the approximately 200 white, are attributed to the Bantu, a group of peoples that spread from the central-western area of Africa to the east and south about 1,500 years ago, occupying the territory of the Bushmen.

Most are found in open places, rocks and ravines, exposed to inclement weather and sunlight, while a few appear sheltered from ledges or inside the caves themselves. The motifs represented are mainly animal and geometric designs, with a few human representations and hand prints.

Giraffes, antelopes, rhinoceroses, zebras, elephants and cows predominate, represented as silhouettes, while the human figures are more schematic, without signs of clothing or utensils and weapons, although they are sexually differentiated.

The white paints are mostly concentrated in the appropriately known Coat of the White Paints , in which at least 7 representations of horsemen and a chariot with wheels appear. These horseback riders cannot be older than 1852, the year this animal was introduced to the area.

Curiously, and despite being older, the red paintings are more elaborate than the white ones. These are sometimes made on top of the red ones, superimposed.

The tradition of the current San natives says that Tsodilo is the place where life arose, and the representations of their ancestors, the red paintings, reflect the tracks of the first animals, and their search for the first waters.

In 2006 archaeologist Sheila Coulson discovered, while investigating in one of the Tsodilo caves, a rock that seems to have the shape of a large snake that appears to have scales depending on whether the light of day or fire falls on it. or move. It could be a coincidence, but digging near the head of the alleged snake found some 13,000 stone artifacts, most of them spearheads, up to 70,000 years old, which could indicate that some kind of ritual took place there.