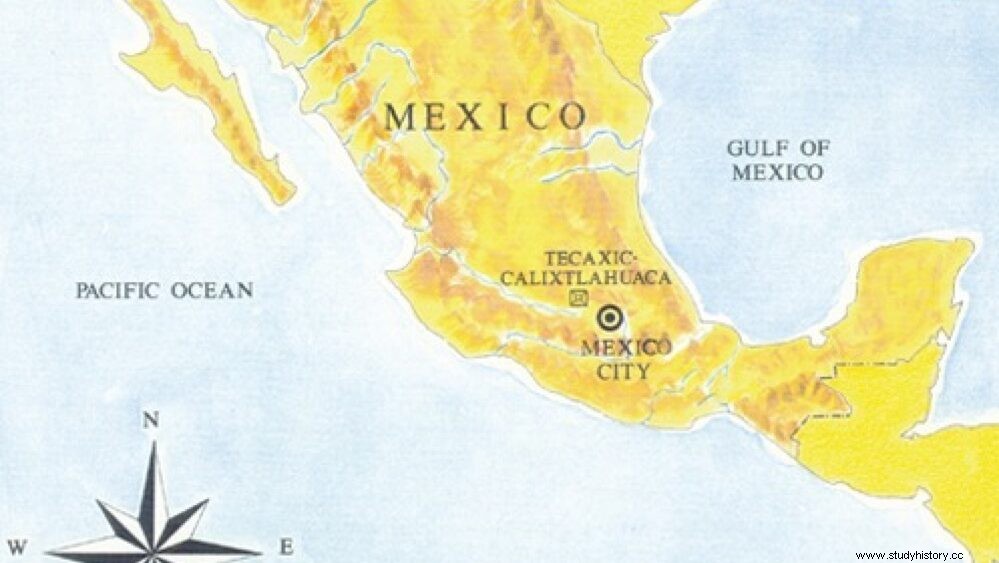

The archaeological site of Calixtlahuaca is located on the side of a hill next to present-day Toluca, in Mexico. The city, in which numerous buildings, temples and other structures have been excavated, was originally built by the Matlatzinca culture under the name of Tecaxic. The Mexicas conquered it during the reign of Axayácatl, destroying it and building a new city, Calixtlahuaca, on it.

The investigations began in the 1930s, under the direction of the archaeologist José García Payón, who brought to light the vast majority of buildings, restoring them. Among the findings made by García Payón there is a singular and controversial sculpture, known as the Head of Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca . It appeared in 1933 in a deposit of offerings or grave goods found under three intact layers of soil of a pyramidal structure.

The set of objects found next to the head It included ceramic fragments, pieces of gold, copper, turquoise, rock crystal, jet and bone, which were dated between 1476 and 1510 AD. However the head , which appeared to be part of a larger figure of which no remains were found, turned out to bear an uncanny stylistic similarity to ancient Roman busts.

It went unnoticed until in 1961 the Austrian anthropologist Robert Heine-Geldern examined the figurine and stated that it must be Hellenistic-Roman, dating it to around 200 BC. Nobody paid much attention to him and the matter was forgotten until 1990.

In that year an archeology student named Romeo Hristov (now a professor of anthropology at the University of New Mexico) located it in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico. Along with Santiago Genovés, he would review the circumstances of the discovery as well as the literature related to it. Both published a study entitled Mesoamerican evidence of pre-Columbian transoceanic contacts in 1999, where for the first time they argued the possibility of Roman origin.

They cited the opinion of Bernard Andreae, who at the time was director of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome, that the head was unmistakably Roman . Furthermore, he added, stylistic examination tells us more precisely that it is a Roman work from around the 2nd century AD, and the hairstyle and the shape of the beard present the typical characteristics of the period of the Severian emperors (193-235 AD), exactly according to the fashion of the time.

And also the discovery of other Roman objects on American soil, such as the coins found in 1963 during the construction of a bridge over the Ohio River in Louisville.

Thermoluminescence tests carried out in 1995 at the Max Planck Institut in Heidelberg did not clarify matters too much, since they yielded such a wide interval (dating the head between the 9th century BC and the 13th century AD) that any origin was possible. According to Peter Schaaf and Günther A. Wagner, who published a commentary on the work of Hristov and Genovés in 1999 (Comments on “Mesoamerican Evidence Of Pre-Columbian Transoceanic Contacts” by Hristov And Genovés, in ancient Mesoamerica ):

The anthropology professor at the University of Arizona, Michael E. Smith, points out four possibilities about the Tecaxic-Calixtlahuaca head :

The first is that it is a hoax. It may indeed be a Roman sculpture, but placed on purpose as a kind of joke. According to Smith, a professor at the University of the Americas named John Paddock used to tell his students that the head It had been a joke conceived by Hugo Moedano, a student who participated in the archaeological work. However, he has not been able to confirm or dismiss this story, since all its protagonists have passed away.

The second possibility is that, even when the head may have a Roman origin, it must have been mixed with the objects from the excavation at a later time, by mistake. It is based on the fact that the archaeologist García Payón did not take exhaustive notes of his finds, and that the collection of artifacts from Calixtlahuaca that can be seen today in the Anthropology Museum of Toluca is full of added ceramics from other excavations.

The third possibility is that the statuette, being equally Roman, was introduced in Calixtlahuaca in the early days of the conquest, something that he affirms was already considered when García Payón published his discoveries in 1960.

And finally, the fourth possibility is that, in fact, this Roman figurine did arrive in some way and at some point in the pre-Columbian period to Mexico, perhaps through Asia. Although Smith states that he seriously doubts the latter option, he does not totally rule it out either.

Hristov and Genovés add that perhaps the wreckage of a Phoenician or Berber ship reached the American shores, taking the figure with them.

To date, none of the hypotheses has been confirmed, nor has it been possible to date the figure with any precision. Nor has any stylistic or comparative analysis with Roman works of the supposed period to which it could belong been published, mainly because few researchers want to risk getting mired in such a controversial issue.