Did the queen of Coba, one of the largest cities in the ancient Mayan world, build the longest known Mayan road to invade a smaller, more isolated neighbor and gain a foothold against the emerging empire of Chichen Itza?

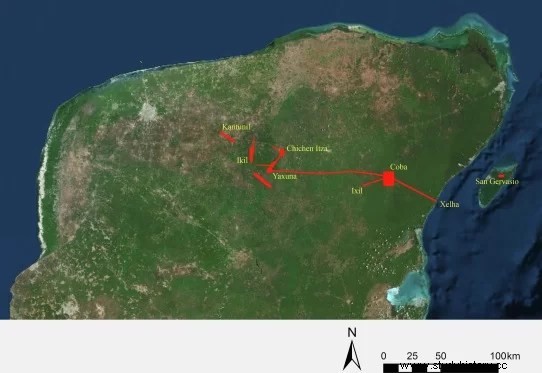

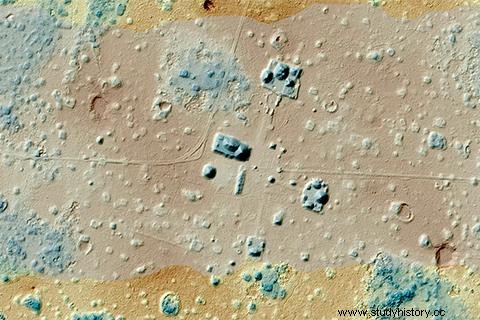

The question has long intrigued Traci Ardren, an archaeologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Miami. Now she and her colleagues may be one step closer to an answer, after conducting the first lidar survey of this 100-kilometer-long stone road that connected the ancient cities of Cobá and Yaxuná on the Yucatán Peninsula 13 centuries ago. .

LIDAR technology is revolutionizing archeology by allowing archaeologists to detect, measure and map structures hidden under dense vegetation that, in some cases, has grown for centuries, engulfing entire cities.

Often deployed from low-flying aircraft, lidar instruments fire rapid pulses of laser light at a surface, then measure the amount of time it takes for each pulse to bounce off. The differences in the times and wavelengths of the bounce are then used to create 3D digital maps of the structures hidden below the surface.

The LIDAR study, which Ardren and her colleagues researchers from the Yucatan Center Interaction Project (PIPCY) carried out in 2014 and 2017 at the Sagrado 1 , or White Path 1 , as this white plaster path was called, may shed light on the intentions of K'awiil Ajaw, the warrior queen who Ardren believes commissioned its construction in the late 7th century.

In a study recently published in the Journal of Archaeological Science , the researchers identified more than 8,000 covered structures of various sizes along the trail. The study also confirmed that the highway, which is about 8 meters wide, is not a straight line, as had been assumed since archaeologists at the Carnegie Institution of Washington mapped its entire length in the 1930s with little more than a ribbon. measuring tape and a compass.

Rather, the causeway was diverted to incorporate pre-existing towns and cities between Cobá, which controlled eastern Yucatán, and Yaxuná – a smaller, older city in the middle of the peninsula. However, isolated Yaxuná still managed to build a pyramid almost three times as big and centuries before the famous Castle from Chichen Itza, about 24 kilometers away.

LIDAR allowed us to really understand the road in much more detail. It helped us identify many new towns and cities along the way, new to us, but pre-existing Arden said. We also now know that the road is not straight, which suggests that it was built to incorporate these pre-existing settlements, and that has interesting geopolitical implications. This highway not only connected Cobá and Yaxuná, but also connected thousands of people who lived in the intermediate region .

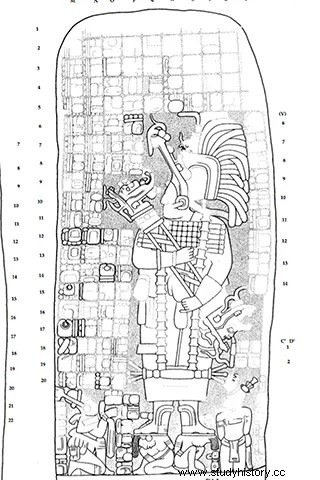

It was in part Yaxuná's proximity to Chichén Itzá, Mexico's most famous Mayan ruin that flourished after Yaxuná and Cobá disappeared, that led Ardren and other researchers to theorize that K'awiil Ajaw built the road to invade Yaxuná and establish itself in the center of the peninsula. Ruler of Cobá for several decades beginning in AD 640, he is depicted in stone carvings trampling his bound captives.

Personally I believe that the emergence of Chichen Itza and its allies motivated the way Arden said. It was built just before 700, at the end of the classic period, when Cobá is making a great effort to expand. It is trying to maintain its power, so with the rise of Chichen Itza, it needed a fortress in the center of the peninsula. The road is one of Cobá's last efforts to maintain its power. And we think it may have been one of the achievements of K'awiil Ajaw, who is documented to have waged wars of territorial expansion .

To test his theory, Ardren, an expert on ancient Mayan society, and his colleagues at PIPCY received funding from the National Science Foundation to excavate ancient hearth clusters along the great white road. Its objective is to determine the degree of similarities between the household items of Cobá and Yaxuná before and after the highway was built. The idea, Ardren said, is that after the highway linked the two cities, the goods found in Yaxuná would show more and more similarities to those in Cobá.

So far, the researchers have excavated clusters of houses on the edge of Cobá and Yaxuná, and they plan to begin a third excavation this summer, at a location determined by the lidar survey. It is located between the two ancient Mayan cities, on the great white road that, according to Ardren, would have shone brightly even in the dark of night.

As he pointed out, the highway is as much an engineering marvel as the monumental pyramids the Mayans erected in southern Mexico, Guatemala, northern Belize and western Honduras. Although built on undulating terrain, the road was flat, with the uneven ground filled with huge limestone boulders, and the surface covered in brilliant white plaster. Essentially the same formula the Romans used for concrete in the 3rd century BC, plaster was made by burning limestone and adding lime and water to the mix.

It would have been a beacon through the dense green of the cornfields and fruit trees Arden said. All the jungle we see today was not there in the past because the Mayans cleared these areas. They needed wood to build their houses. And now that we know that the area was densely occupied, we know that they needed a lot of wood. Because they also needed it to burn the limestone and build the longest road in the Mayan world 13 centuries ago .