A travel thorn that will almost inevitably stick in anyone who visits Egypt is the frustration of not being able to enter the QV66, one of the most beautiful corners of the Valley of the Queens. It is the tomb of Nefertari, the favorite wife of Pharaoh Ramses II, who had already built in her honor the temple of Hathor that accompanied his in Abu Simbel. I say frustration because, unfortunately, the place is closed to the public (with a few expensive exceptions, as we will see).

This Nefertari should not be confused with other namesake characters from the New Kingdom, such as the wife of Thutmose IV (who was a century and a quarter earlier), or Ahmose-Nefertari, daughter of Sequenenre Taa and mother of Amenhotep I (who lived almost three hundred years before).

The one we are dealing with is distinguished from the others by several things, starting with the main title linked to her name, Meritenmut, which translates as « Beloved of Mut «. Let us clarify that Mut was the Egyptian mother goddess, wife of Amun, and that Nefertari means «Beautiful Companion «.

She also differs from her by the power that she came to enjoy, since only predecessor queens such as Hatshepsut and Tiy, or later queens such as Tausert and Cleopatra, could be compared to her in that regard. She was so to such an extent that she even negotiated a peace treaty with the Hittites, that of Qadesh, for which she exchanged correspondence with Puduhepa, the wife of Emperor Hattusilli III. In fact, Ramses II always had her by her side and in the aforementioned temple he had a significant gloss inscribed:« A work belonging for all eternity to the Great Royal Wife Nefertari-Meritenmut, through whom the Sun shines «.

However, little is known about her. At least from her origins, which were noble in all probability; thus it is deduced from her discovery in her tomb of a cartouche with the name of Ay, daughter of the usurper Horemheb, of whom she might be a granddaughter or great-granddaughter and, therefore, she would be related to the XVIII dynasty.

There are also those who venture that she could have been the daughter of Tandyemy, perhaps the daughter of Horemheb, venturing that she could have married Seti I, which would mean that Nefertari would be the sister or stepsister of her own husband, Ramses II (a common practice among Egyptian leaders). .

This last theory would be based, among other things, on the fact that both were married while still teenagers, before he succeeded his father and even being associated with the throne by him. Of course, Ramses already had a wife for a couple of years, Isis-Nefert, about whom not much is known and who on top of that went into the background, despite the fact that she was the one who gave birth to the one who long after - due to the longevity of his father - would be the heir:Merenptah (who took his little sister Isis-Nefert II as his wife and both had the future pharaoh Seti II).

Nefertari's year of birth is unknown, but calculations suggest that she was around fifteen when she also gave birth to her first child Amenherkhepeshef, who was followed by at least eight others. It should be noted that, in his very long life (ninety-three years), Ramses II came to father more than a hundred and a half offspring with his dozens of consorts (apart from those mentioned, there were five other queens, including two of his own daughters), wives and concubines.

If Nefertari's birth date is ignored, on the other hand there seems to be a certain historiographical unanimity on the date of her death:in the year 1255 BC, when her age would be around forty or fifty years and Ramses had been ruling for twenty-six. It is usually calculated based on the fact that the temple of Hathor, in Abu Simbel, was inaugurated by the pharaoh in the twenty-fifth year of her reign and he did not do so accompanied by her but by another Great Royal Wife, her daughter Meritamón de ella. . Likewise, the monument still had a decade to go to be completed and when it was finally finished, inscriptions were added describing the death of Nefertari.

Therefore, she did not get to see him in all his splendor, despite being dedicated to her person. In return, the heartbroken widower had what was to be the largest and most beautiful tomb in the Valley of the Queens built.

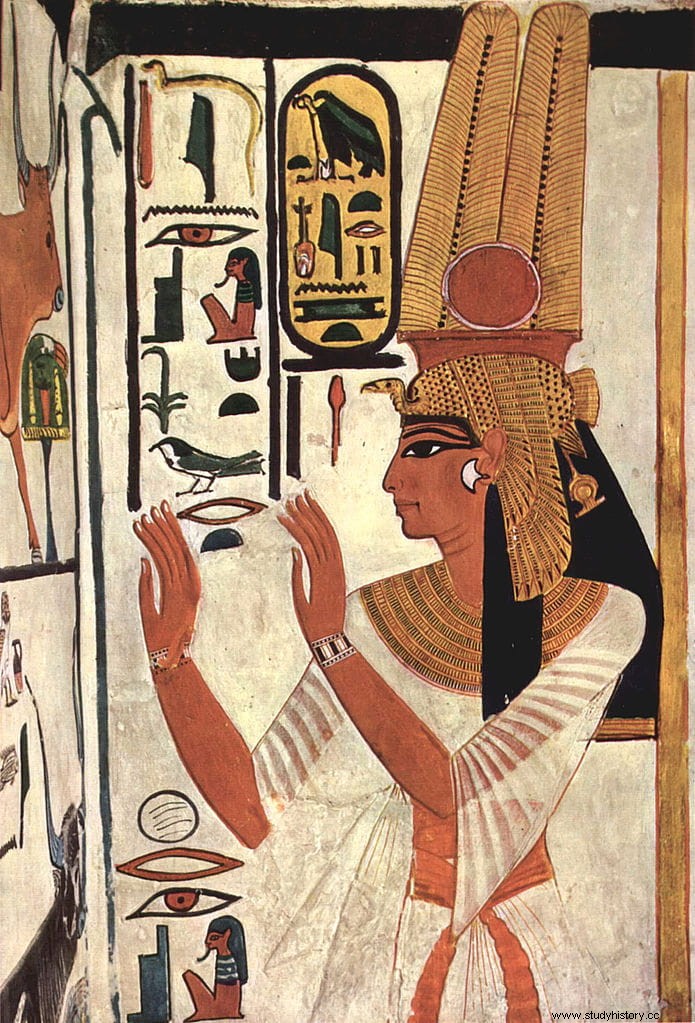

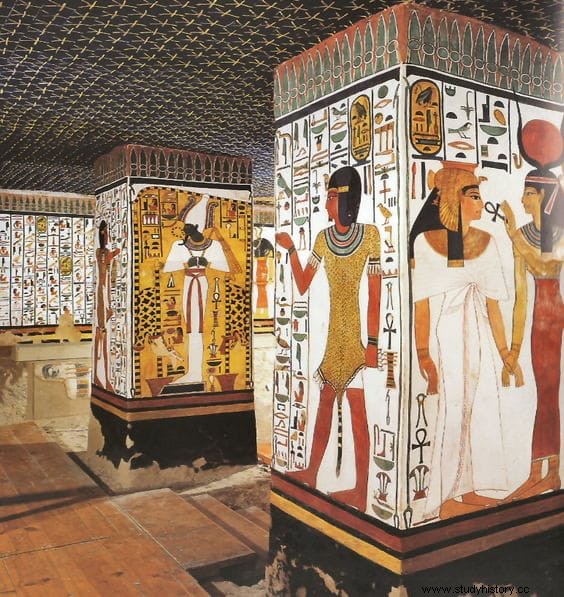

It is a hypogeum (sepulcher excavated in the rock) of five hundred and twenty square meters, whose walls are covered with splendid paintings that allow us to get an idea of the physical aspect that Nefertari had, since she appears portrayed several times and also without the presence of Ramses in no corner of the site, something unusual.

It was the Italian archaeologist Ernesto Schiaparelli who discovered the site in 1904, during the first of a dozen excavation campaigns that were to last seventeen years. Schiaparelli, who had studied at the Sorbonne with the prestigious Egyptologist Gaston Maspero (a Frenchman from an Italian family), directed the antiquities section of the Egyptian Museum in Turin, at the time the second most important worldwide after the one in Cairo, and in the initial triennium he explored about eighty valley tombs, all already looted.

Also Nefertari's had been, although pieces of her grave goods were still found as ushabtis (mummiform statuettes with psalms to help the deceased in the afterlife), gold bracelets and a Greek silver pendant in the shape of labrys (double-headed axe) which the queen is seen sporting in one of her portraits. The mummy was not; at least complete, since legs were recovered that would correspond to a person of the bone structure and the age of Nefertari when she died (they are preserved in Turin).

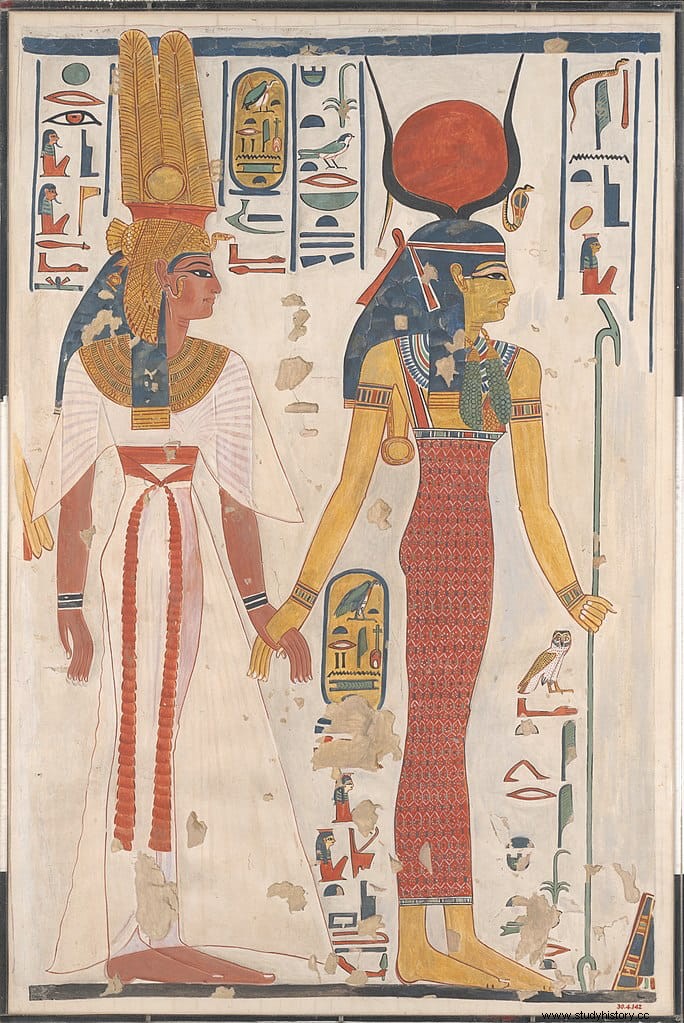

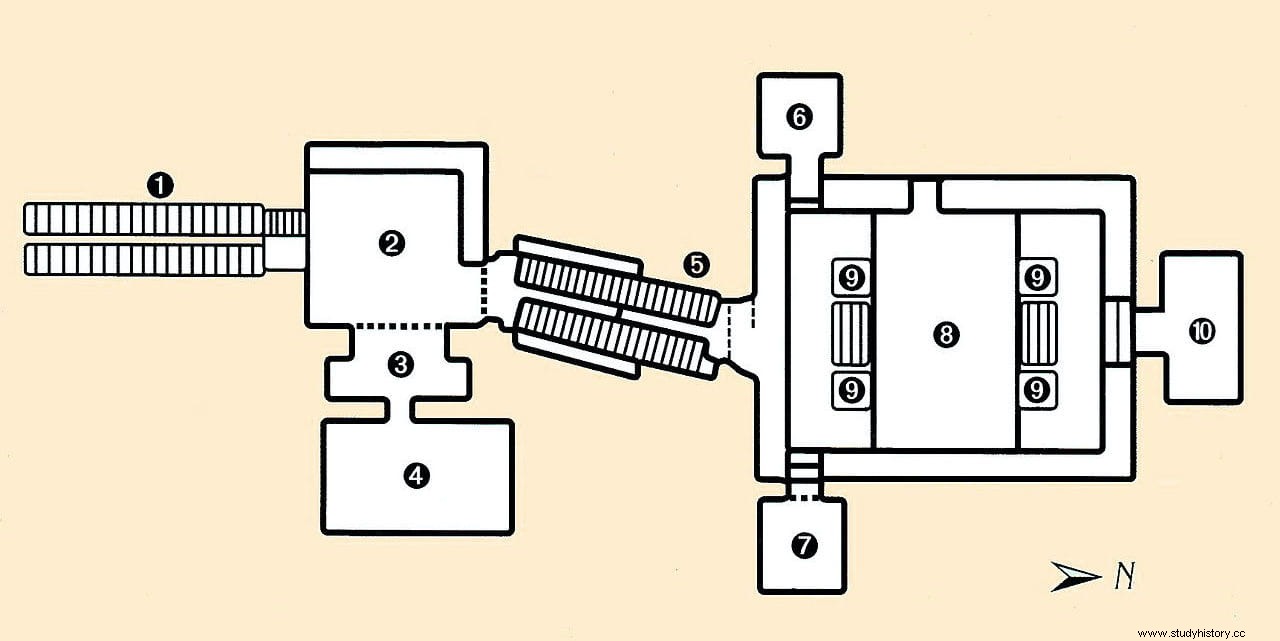

As for the tomb itself, it is accessed by going down a staircase that leads to the antechamber, where the first frescoes can be seen. Thematically they illustrate chapter 17 of the Book of the Dead , showing on the ceiling a celestial vault with five-pointed stars, as well as an eastern wall with Osiris and Anubis flanking the door to a lateral chamber that has scenes of offerings represented. Before, there is a hall where Nefertari is seen appearing before the gods.

In the northern wall is the stepped access -and with a central ramp-, deviated towards the north of the longitudinal axis, descending towards the funerary chamber. It consists of a large quadrangular room (ninety square meters) with another astronomical ceiling supported by four pillars.

At the time, the red granite sarcophagus that contained the mortal remains of the queen was in the center of the room, whose walls also present pictorial decoration based on the Book of the Dead (chapters 144 and 116, on the journey of the deceased to the afterlife). The chamber has three annexes that served to house the trousseau.

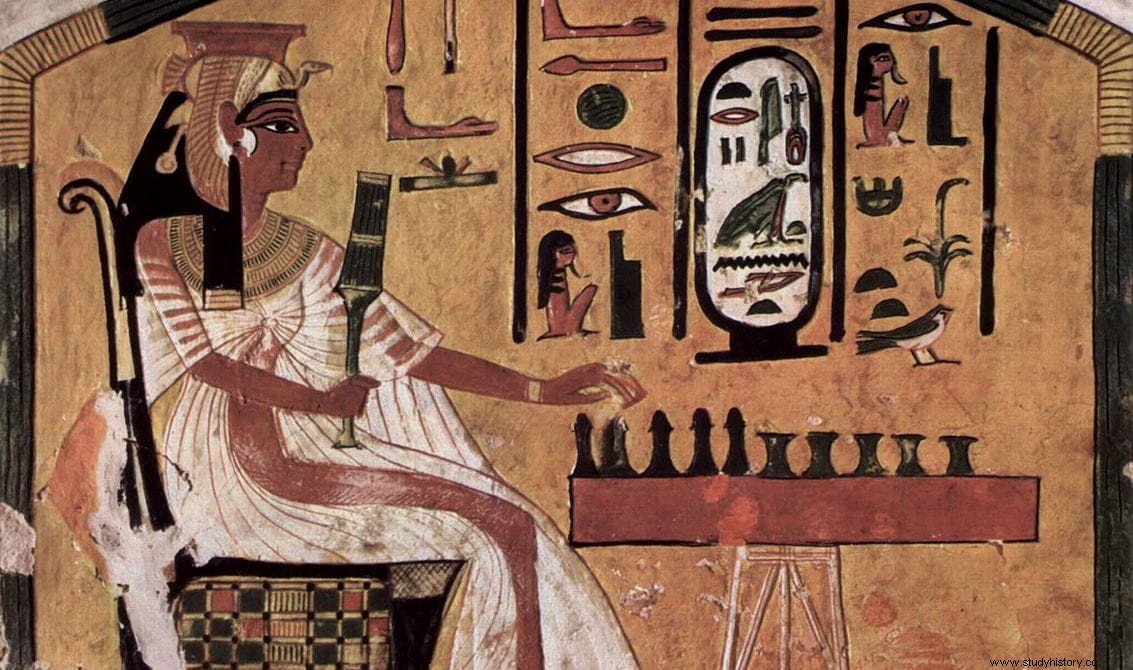

Apart from the size of the hypogeum, the most impressive are the paintings. For various reasons, beginning with the fact that it constitutes an interesting source of documentation on Nefertari's domestic life:the queen appears playing sennet, from which many deduce that there was a board with her pieces that must have been stolen, and together with Toth as if she were a scribe, which has led to the assumption that she was literate and would have even practiced literature.

But another reason is the artistic beauty itself of the pictorial decoration, above average and with the unusual peculiarity of not capturing Nefertari with the characteristic Egyptian hieratic style but with a certain naturalism; it is something especially noticeable in the mural of the sennet game, for example, but also in the others:expression wrinkles can be seen on the face, rouge on the cheeks, folds on the neck... It does not reach the end of the Amarna period, but still So it is quite unusual.

It also helps that the colors maintain their vibrancy thanks to relatively good preservation, which is rare in all of Egypt. And that the sodium chloride of the rock that houses the tomb, in combination with the fungi, the bacterial contamination and the humidity caused by the visitors, degraded them and for this reason it became necessary to intervene as early as 1934. attempts to tackle the problems and in 1950 QV66 had to be closed to the public, remaining so until 1977 with no improvement.

In 1986 a study of the paintings was undertaken by an international team that decided to restore the paintings. Work began two years later, removing the layer of dust and soot that covered them, and ended in 1992. However, to prevent further damage, it was decided to restrict the entry of onlookers as much as possible. It remained that way until five years later the Egyptian government ordered its reopening, admitting a maximum of a hundred and a half tourists at a time inside.

Faced with the danger of the deterioration reproducing itself, in 2006 it was closed to the general public again, allowing only a small quota of twenty people who had to pay three thousand dollars, money destined to defray the costs of maintenance, conservation and restoration. At the end of 2019, an entrance fee of one thousand four hundred Egyptian pounds (about seventy-four euros) or the acquisition of the Premium Luxor Pass was imposed. (one hundred and eighty euros), which includes the ticket. The covid pandemic, paradoxically, will have helped.