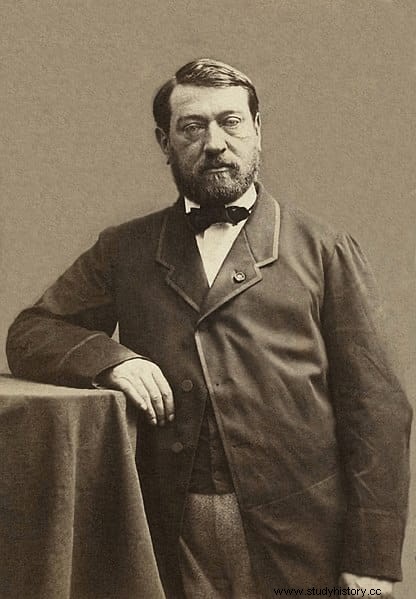

In 1850 the French Auguste Mariette, interested in the study of Egyptian hieroglyphics and the Coptic language, was commissioned by the Louvre Museum to travel to Egypt in search of Coptic, Syriac and Arabic manuscripts. He was to buy as many as he could find, to maintain the primacy of the Parisian museum over other public and private collections.

But inexperience and ignorance of the place meant that he was not very successful in his task. To avoid returning to France empty-handed, and fearing that this might be his last chance to visit the country, he got a group of Bedouins to agree to serve as his guide and set out to visit monuments, temples and archaeological sites.

Thus while visiting the Memphis necropolis and the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, he observed the head of a sphinx protruding from the desert sand near the pyramid. In order to unearth it, he hired a group of 30 workers, who little by little brought to light an entire avenue flanked by sphinxes (it is estimated that it had some 600 sphinxes, some of which can be seen today in the Louvre Museum).

Not only that, the avenue led to an underground complex that turned out to be a serapeo, a set of temple-tombs where Apis bulls were buried. These were bulls that were supposed to embody the sun god Ptah, so that when one died he was buried in a sarcophagus with a great ritual celebration to bring about his rebirth. Then the priests looked for a successor for him.

On November 12, 1851, Mariette, using explosives to break the entrance to the underground complex, managed to gain access to the interior. What she found inside her far exceeded her expectations. In addition to the huge and spectacular sarcophagi of more than 60 bulls, spanning from the time of Amenophis III (reigned ca. 1390-1353 BC) to that of Ptolemy X Alexander (110-88 BC), he discovered the virtually intact tomb of the priest Khaemwaset, son of Ramses II.

Mariette reported the find to the French authorities, who immediately relieved him of his task of collecting manuscripts, and advanced the necessary funds for the continuation of the excavations. For four years he remained in Egypt excavating and extracting the treasures of the serapeum. The French government, the Louvre museum and the Egyptian government reached an agreement to share the finds 50/50.

The serapeo consists of a large tunnel with more than 30 lateral chambers connected by corridors and passageways that contain the sarcophagi of the bulls. Unfortunately all of them were empty at the time of discovery. This great gallery had been built by order of Khaemwaset between 1279 and 1213 BC. Another gallery had been added to it in the time of Psammetichus I (664-610 BC), which was later enlarged by the Ptolemaic dynasty to reach 350 meters in length by 5 in height and 3 in width. A new service gallery was also built. In total, the complex is about 7 kilometers long.

The impressive sarcophagi of the bulls are made of granite and diorite, and some weigh up to 70 tons (including the lid), being among the largest of Antiquity. The mummies of the animals were destroyed by the Coptic monks, who settled in the vicinity of the serapeum when the Roman Emperor Honorius ordered it to be closed forever.

But before that, in Ptolemaic and Roman times the complex formed a vast sacred perimeter linked to the valley by the famous dromos described by Strabo. At the end of this road there was an esplanade where Greco-Roman sanctuaries and temples were erected, including a hemicycle dedicated to Greek writers and philosophers, whose statues are preserved in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and constitute the only representations of these characters that has come to our days.

A little further north of the road was a chapel dedicated to Apis containing a life-size statue of the bull god, with a sun disk held between the horns. Today it is kept in the Louvre. The dromos it continued towards the enclosure of the serapeum and ended in an entrance framed with reclining lions, a monument erected by Nectanebo I, who also ordered the construction of the avenue of sphinxes.

In the chambers of the bulls, Mariette found dedicatory stelae indicating the reign during which the bull was born, its year of enthronement in the temple of Ptah, its lifetime, and the date of its death and burial, specifying the reign in which the ceremony took place. These stelae are today important documents that shed light on reigns that the royal annals have not preserved or of which few details are available from other sources (some researchers consider them more reliable than the list attributed to Manetho).

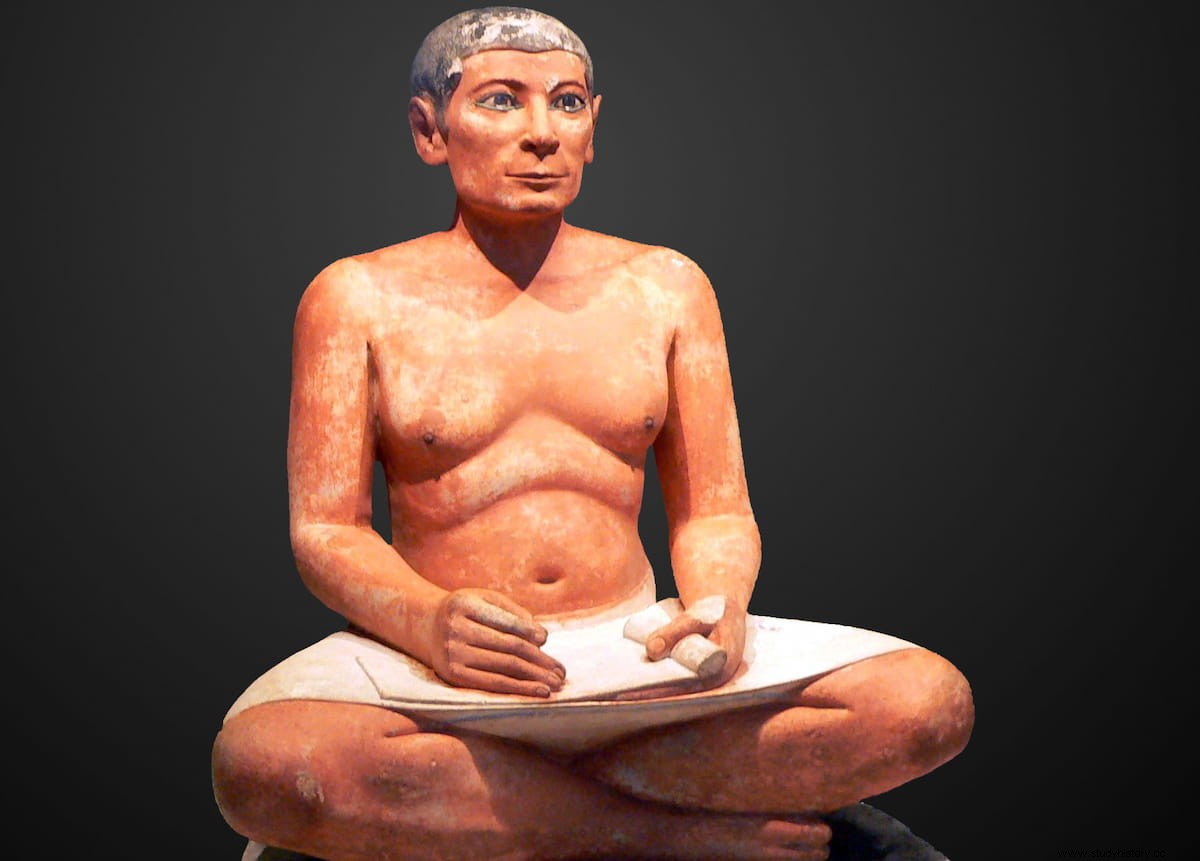

Among the bulls of the serapeum Mariette found those buried during the reigns of the Persians Darius I and Cambyses II. And among the objects and artifacts found inside the complex, the famous seated scribe stands out. , a figure probably representing a high official. The statue is made of limestone, with eyes carved from rock crystal, white quartz and ebony. The scribe is sitting cross-legged with an unfolded papyrus on top of them. It is probably one of the most realistic Egyptian sculptures we know, compared to the hieratic way in which the pharaohs and gods were represented.

As for Mariette, upon her return to Paris with 230 boxes of artifacts (the same number that remained in Egypt), he was promoted to the position of deputy curator of the Louvre museum.

But less than a year later he could not resist and returned to Egypt. The Egyptian government created for him the position of Conservator of Egyptian Monuments in 1858, and in 1863 he created the Cairo Museum, to protect the archaeological sites and stop the systematic looting.

In 1860 alone he directed more than 35 new excavations, while taking care to preserve the places already excavated. Appointed Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service , he was successively distinguished with the ranks of bey and pacha .

But in 1878 his museum was destroyed by floods and all his notes and drawings were lost. On January 18, 1881 he passed away, and was buried in a sarcophagus, which is in the Garden of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, surrounded by the busts of other famous Egyptologists.