It has long been assumed that proximity to resources determines settlement patterns, and that cities are generally founded near water and fertile farmland. But a new study challenges this idea, using the example of an ancient city in present-day southern Mexico.

The researchers maintain that Monte Albán, the largest city in its region for more than a thousand years, was not located near particularly good farmland. But what it did have since the city's founding was a defensible hilltop location and a more collective form of government that drew people both into and around the settlement.

We wanted to understand why Monte Albán was founded where it was , says Linda Nicholas, first author of the study in Frontiers in Political Science and Associate Curator of the Field Museum.

Monte Albán is located in the Valley of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. Founded in 500 BC, it grew rapidly and remained the main metropolis in the region for 1,300 years, longer than most, if not all, other pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican cities. We have been working in the Oaxaca Valley for 40 years, and both we and our colleagues have asked ourselves what attracted so many people to Monte Albán and its surroundings, and what allowed the city to stand for so long , says Gary Feinman, MacArthur Curator of Anthropology at the Field Museum and co-author of the study. Over the years, some competing ideas have been proposed .

One hypothesis to explain the rapid growth of Monte Albán is coercion, that is, the idea that powerful rulers forced people to move there. Another possible explanation is that people went there because the land was good for farming. To examine the validity of these possible explanations, Nicholas and Feinman reviewed decades of research spanning both Monte Albán and the surrounding Oaxaca Valley.

To test the argument that Monte Albán attracted people because of the quality of its farmland, the researchers drew on studies of modern land use in the valley to map the different kinds of land based on the availability and permanence of water, the most important factor for the yield of crops in the valley. Good, well-irrigated land was unevenly distributed throughout the valley, so that some areas had a much higher potential yield than others. While pre-Monte Albán settlements were more concentrated in the more productive parts of the valley, Monte Albán was not. Land quality was less of a factor in settlement decisions at the time of Monte Albán's founding, both for the city and for nearby settlements.

Linda's analysis of land use shows very clearly that Monte Albán was not located near the richest land. Whether you look at the land itself or the labor to work it, agricultural productivity cannot explain the location of Monte Albán says Feinman.

So the fertile land hypothesis does not hold in the case of Monte Albán. Feinman and Nicholas also investigated the possibility that people were forced to come to the region. This part of the project was based on decades of archaeological survey work. In the 1960s, archaeologists began to ask different questions about ancient societies, beyond just collecting and classifying artifacts Nicholas says. When you excavate a site, you only get an image of a very small part, and it's also destructive and expensive .

If it comes to answering questions about how the first cities formed and how long they lasted, the dig, with its limited portal into the past, doesn't answer them Feinman says. If you want to know the city of Chicago, excavating a house, a block, or even a neighborhood will not provide information about the growth of the city center in relation to the Chicago River and Lake Michigan, nor about their relationship with a broader network of settlements in northern Illinois and beyond. The same goes for ancient cities:a more macro view is needed to understand their growth and decline compared to the areas around them .

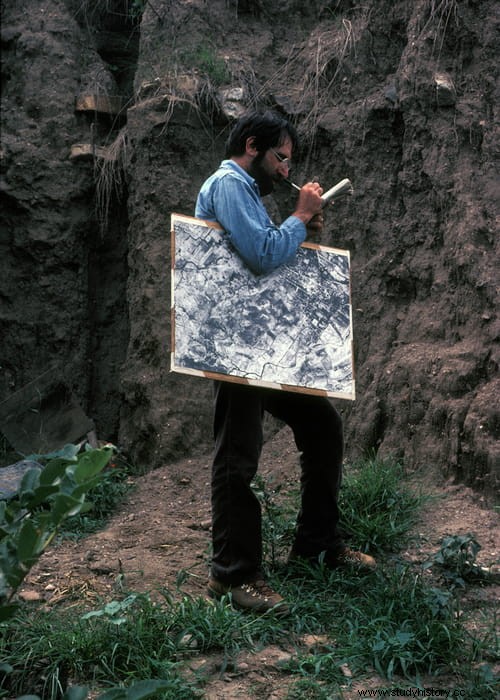

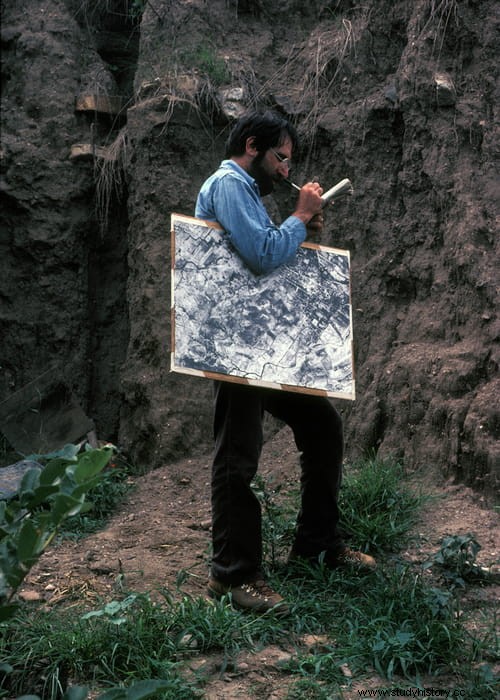

To get this bigger picture of where people lived and how their settlement patterns changed over time, Feinman and Nicholas collaborated with Richard Blanton and Stephen Kowalewski in Oaxaca to study one of the world's largest contiguous study regions. For our systematic study, we used aerial photographs and maps to guide us as we walked throughout the valley. When we found archaeological sites, we made notes of what we found and where and made collections to determine periods of occupation Nicholas says. We and our colleagues ended up covering thousands of square kilometers in the Oaxaca Valley and adjacent areas . This research over the years has been supplemented by deeper excavations by many scholars at key sites.

This broader view of life in and around Monte Albán, gleaned from both surveys and excavations, provided researchers with new insights over the years. We learned that in Monte Albán and other settlements in pre-Hispanic Oaxaca, the bulk of the residents lived on flattened terraces, which were built on the slopes of hills. From excavations by us and others, we gained insight into terraced life, where people lived in single houses with multiple rooms around a courtyard. Domestic units used to share a front retaining wall, and drains used to separate residences Feinman says. People not only lived close together, but they also had to be very cooperative from one household to another, because if a part of the retaining wall collapsed or the drain got clogged, they had to work together to fix it .

The inhabitants of Monte Albán were also economically interdependent, exchanging handicrafts and food in the hazardous agricultural environment in which they lived. Although no large food storage facilities have been found, there are indications that city residents engaged in market exchanges, which may have buffered the region's unpredictable rains. Cooperative defense and economic opportunity drew people from afar to the early days of Monte Albán.

The high degree of cooperation among Monte Albán households was reflected to some extent in the political organization of Monte Albán as a whole. Compared to more autocratic societies, such as the Classic Maya, Monte Albán seems to have had a more collective form of government Nicholas says. Autocratic societies, ruled by despots, in which a small group of people wielded all power, often had architecture that reflected their form of government, with grand, lavish palaces and elaborate burial places for the rich and powerful. Despotic rulers serve as a poster child for their regimes, often marked by enlarged and personalized monuments. Monte Albán, however, is characterized by non-residential public buildings, temples, and large, relatively open and shared plazas. Given the longevity of the site, the number of monuments in which rulers appear is small.

Although defense was a key factor in the founding and location of Monte Albán, there is no indication that the first occupants were forced to move to this dense hilltop site where its agricultural prospects were somewhat risky, efforts were needed interpersonal relationships to maintain their residences, and the residential settlement was densely populated. However, health measures indicate that the inhabitants of Monte Albán were generally better off than residents of other pre-Hispanic cities, and the institutions established in Monte Albán contributed to their well-being, attracting people from afar despite these challenges. .

Given that people were probably not forced to come to Monte Albán, and that they did not come for the productive farmland, the question remains:why did Monte Albán grow so rapidly and remain large and important for so long?

We think we have a framework that is based more on cooperation Nicholas says. Building on the work of other scholars such as Margaret Levi and Richard Blanton, Feinman hypothesizes that it's a kind of mutual relationship between people who have power and those who don't. In this case, the powerful may have coordinated defense, helped organize market exchange, and carried out ritual activities that increased community solidarity. On the other hand, the bulk of the city's population produced food and other goods that sustained the settlement and, through taxes, supported the government. It was a collaborative process that was based on compliance .

Feinman notes that the city's architecture could include clues to this cooperative relationship between classes that brought people to Monte Albán. From the very foundation of the place, there was a large main square where people could gather and express their voice, at least sometimes. People may have moved there for reasons of defense and economic opportunity she says. But on the other hand, to shore up and support these new institutions, farmers probably had to give up some of their surplus. So it's kind of a give and take .

Although Feinman and Nicholas point out that this study is just one case study, about one city, it does have some lessons for us today. Monte Albán was a city in which a new social contract was written at its foundation. It was somewhat more equitable and less elite-focused than what had happened before Feinman says. And with its collective and relatively equitable rule, it endured for more than a millennium. However, when it collapsed, the city's population dwindled dramatically and many of its institutions were dissolved, ushering in a period of more autocratic rule .