An Aztec skull mask discovered at the Templo Mayor site in Mexico City, ancient Tenochtitlan.

An Aztec skull mask discovered at the Templo Mayor site in Mexico City, ancient Tenochtitlan. OFFERINGS. Scary heads! Unearthed from the ruins of Mexico City's famous Templo Mayor – the main ceremonial complex of ancient Tenochtitlan – a series of eight face-perforated skulls unique to Mexico have puzzled researchers for years. Who could be the victims thus transformed into morbid sacrificial offerings, some of which were worn as masks among the Aztecs? For what purpose had they taken the trouble to transform these heads by removing their bony parts, by piercing them at the level of the nasal cavities with blades of cut flint, and by replacing the eyes with inlays of shell and pyrite? ? Especially since at their side were around thirty other decapitated skulls, without the slightest alteration. Were they specific characters?

The answer is in a recent publication in the journal Current Anthropology in which Corey S. Ragsdale, anthropologist at the University of Montana, Missoula (USA), presents the results of new analyses. These poignant relics, exhumed at the level of the temple of Huitzilopochtli (deity of war and of the sun), would in fact be those of defeated warriors, captured during the multiple "flower wars*" in which the Aztecs engaged (read box) to make their sacrifices. The Templo mayor indeed contained two major sanctuaries, one dedicated to Tlaloc, the god of rain and storms, and the second to Huizilopochtli, the bloodthirsty god. It was at the top of the latter that the ritual sacrifices were performed, before the bodies of the victims were thrown down the stairs of the monument. The examination of the 8 skull masks has thus made it possible to establish that the victims had been immolated during the reign of the Aztec sovereign Axayacatl (1469-1481). Their comparison with more than 127 unmodified skulls further demonstrated that they belonged to high-ranking (elite) warriors, which was not the case for the other relics.

The age of all the victims (reworked skulls or not) could be established between 30 and 45 years old, all being mostly male. The study of their dental condition also made it possible to trace their geographical origin. "They came from western Mexico, the Gulf Coast and the Valley of Mexico" , specifies Corey Ragsdale, joined by Sciences et Avenir. But it is the pathologies detected that have above all made it possible to establish the difference in social status. "Only the unmodified skulls showed significant traces of pathologies, dental wear and deficiencies due to high nutritional stress, and not the skull masks" , confirming a precarious social origin for some, privileged for others.

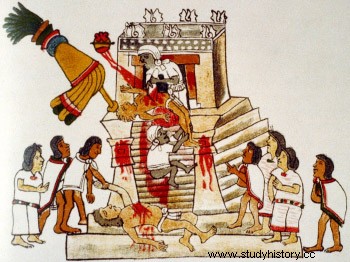

Human sacrifices at the Templo Mayor

Illustration of sacrifice from the Codex Magliabechiano, an Aztec codex dating from middle of the 16 th century

Human sacrifice was a large part of the religious ideology of the Aztecs, as well as a means of subjugating defeated populations. It was common to carry out beheadings, heart extractions (cardiectomy) or dismemberments. Although the number of Tenochtitlan victims is unknown, estimates based on ethnohistorical data often point to thousands of cases. A figure of 20,000 killed in a single year even appears from time to time in the documentation. For Eric Taladoire, professor emeritus of pre-Columbian archeology at the University of Paris 1-Panthéon Sorbonne, these would be fanciful figures whose sources have been misinterpreted, and which have nothing to do with reality.

The Flowery War

The Floral War is the name translated from Nahuatl Xochiyaoyotl which was attributed to battles between the Aztecs (meaning Mexica, and their Triple Alliance allies - Alcolhuas and Tepanecs), the inhabitants of Tlaxcala or neighboring cities in the Valley of Mexico. Very codified, these wars essentially served to seize prisoners to sacrifice them to the gods.