For this 5th episode of the Notebooks of Egypt, the research mission which studies the paintings of the Theban tombs returns to the work of Christian Leblanc Honorary Research Director at the CNRS, who has been working in the west of ancient Thebes for forty years. 'years.

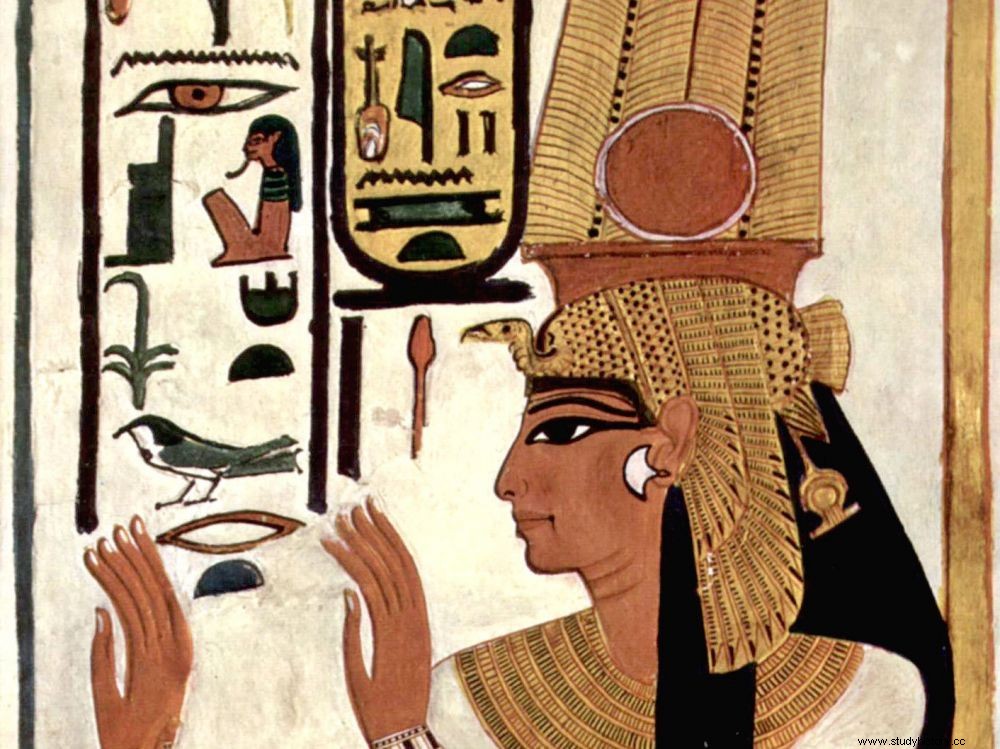

Portrait of Queen Nefertari in her tomb in the Valley of the Queens

Christian Leblanc, Honorary Research Director at the CNRS, worked there for a long time in this Valley of the Queens, patiently exhuming the tombs of the queens and princes of the Ramesside period, from the 19 th and the 20 th Dynasty. Many royal wives of the 18 th Dynasty, known only by the monuments, are however still missing.

©The Valley of the Queens seen from the sky (LAMS/MAFTO/CNRS)

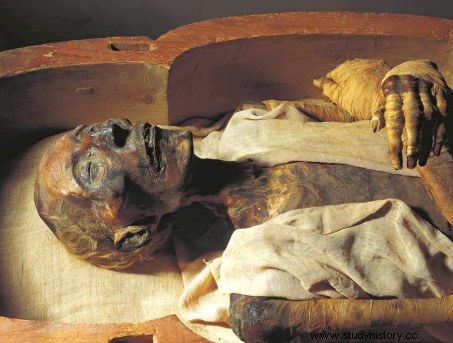

It is indeed possible that their mummified bodies were gathered in a sacerdotal hiding place, like the one discovered not far from Deir el Bahari in 1881. This cache contained the bodies of about forty Egyptian sovereigns. They rest today in the room of the mummies of the Cairo Museum around that of Ramses II himself.

Mummy of Ramses II preserved in the Cairo Museum ©LAMS/MAFTO CNRS

For more than twenty-five years, Christian Leblanc and the members of his team have been studying the monuments of eternity of this great king, his Château-de-Millions d'Années or memorial temple, the Ramesseum, and his eternal home, tomb bearing the number KV7 in the famous Valley of Kings. In this monument, the work is coming to an end. But the clearing of the tomb had discouraged more than one since the 19 e century. It has in fact been repeatedly invaded by mudslides which have formed a compact and hard mass there, while literally exploding the already geologically fractured limestone in the lower parts of this immense hypogeum.

It took all the tenacity of Christian Leblanc to overcome this perilous search. The monument now requires major support and restoration work before it can finally be presented to the public. It is one of the largest royal tombs in Thebes.

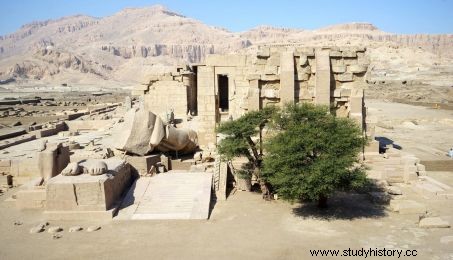

The Ramesseum seen from the North ©LAMS/MAFTO/CNRS

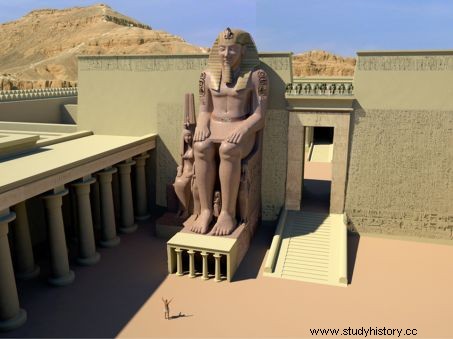

In close collaboration with the Center for Study and Documentation on Ancient Egypt (CEDAE) in Cairo, and with the providential and vital financial support of the Association for the Safeguarding of the Ramesseum, the MAFTO (Mission Archéologique Française de Thèbes-Ouest ) has also been committed for a quarter of a century to the scientific study, restoration and enhancement of the Ramesseum, a religious complex covering nearly six hectares. The site had already been excavated by several teams since the end of the 19 e century, revealing an imposing and romantic ruin, including the remains of an enormous monolithic granite colossus which, at 20 meters high and weighing some 1,200 tons, is one of the largest statues ever carved in the world.

The imposing remains of the granite colossus that adorned the first courtyard of the Ramesseum ©LAMS/MAFTO/CNRS

The patient excavations carried out by the French team also focused on the study of hitherto despised remains which revealed the complex history of the site which today can no longer be described only as the temple of Ramses II:this worship space in fact first housed a popular necropolis at the time of the Middle Kingdom, a necropolis whose existence continued throughout the beginning of the New Kingdom, no doubt around a venerated sanctuary, perhaps dedicated to a local deity of Hathoric essence. The space was then completely leveled to accommodate a new sanctuary. But the original date of the latter seems to go back to the end of the 18 e Dynasty and it may be that Ramses II was able to take advantage at the very beginning of his reign of a building still under construction, but already well advanced.

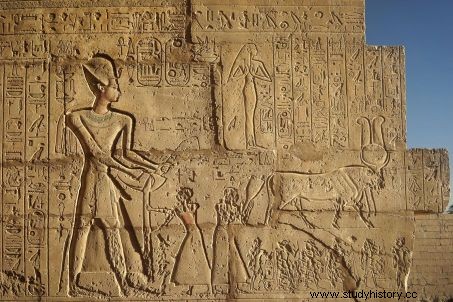

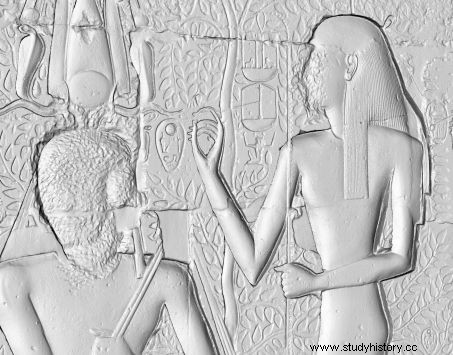

Ramses II cuts the first sheaf in honor of the harvest and the god Min, symbol of agrarian fertility ©LAMS/MAFTO/CNRS

The walls of the temple still show some highlights of the reign of the great Ramses, such as the course of the famous battle of Kadesh. But this temple is above all a place of worship dedicated to Amon, the greatest god of Egypt, and its iconographic program is entirely dedicated to the divinization of Pharaoh, in order to allow him to blend into the divinity and participate in it. to the maintenance of the cosmos for millions of years.

360 degree view of the hypostyle hall of the Ramesseum ©LAMS/MAFTO/CNRS

The Ramesseum also retains traces of the existence of the hundreds of priests who ensured its operation and whose painted funeral chapels we are studying today. Around the stone temple stood mudbrick structures housing the kitchens, granaries, cellars, stores of honey, oil, ointment and perfumes for the daily worship taking place there. These reserves, which brought together the production of numerous agricultural and artisanal estates, were also intended to feed local communities of royal officials, such as that of the artisans of Deir el Medineh, a model village, located a few hundred meters to the west. It was at the Ramesseum that these handpicked workers to dig and decorate the tombs of the Valley of the Kings, decided one day to set up the first picket line in history, when they had not been paid since. long months by a pharaonic regime in full decline.

A place of worship

Archeology has also revealed to us that these monuments of eternity were not in fact destined to last. Just over a hundred years after Ramses II died and was buried in his gigantic burial chambers, the temple ceased to function as an economic entity. These ancillary structures were dismantled and some of its masonry reused not far away in a new memorial building of an equally imposing size erected by Ramses fourth of the name.

The stone temple nevertheless continued to be a place of veneration and a new necropolis settled there, housing the vaults and chapels of worship of members of the royal family and many priests. A few centuries later, it ended up being engulfed in turn by buildings erected in the name of sovereigns of Greek origin, the Ptolemies, a few kilometers further south. Freestone was expensive and the temple of Ramses II had become a ruin that the god Amun no longer deigned to inhabit.

3D scan of a wall showing Ramses II seated under the sacred persea ©LAMS/MAFTO/CNRS/insightdigital.org

He was soon replaced by the god of the Christians who set up a church in a hall where a relief was still visible showing the greatest of the Ramesses seated under the fruit-heavy fronds of the persea of Heliopolis the dynastic tree of Pharaonic royalty. /P>

A quarter of a century has therefore enabled the MAFTO teams to reveal with patience and passion the long and complex history of a particularly fascinating sector of ancient Thebes. But almost half of the economic complex still remains to be excavated and restored to allow tourists who enter this majestic ruin to appreciate its power, while retaining its unique and bewitching charm, often ignored by the most eager visitors. /P>

3D rendering of the granite colossus that inspired Shelley's poem ©LAMS/MAFTO/CNRS/insightdigital.org

Ozymandias

At 19

th

century, era of the Enlightenment and the revolutions against the tyranny of the old regime, the ruins of the statue of Ramses II evoked for a freedom-loving English poet, the vanity of these gigantic constructions, but less durable than would have been wished by the King of Kings.

Here is this poem by Shelley, written in 1817, titled Ozymandias

I met a traveler from an ancient land

Who says:"two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunken lies a broken face, whose frown

And the puckered lip, and the sneer of cold command

They say that the sculptor knew how to read these passions

Which still survive, imprinted on these lifeless things,

To the hand that imitated them and to the heart that nourished them.

And on the pedestal appear these words:

"My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings,

Look at my works, O mighty ones, and despair!"

There's nothing left. around the ruin

Of this colossal debris, infinite and bare,

The lonely, even sands stretch far.

Notebooks of Egypt, 1st episode:how did the painters of ancient Egypt work?

Notebooks from Egypt, 2nd episode:Discovering the funeral chapel of Nakhtamon.

Notebooks from Egypt, 3rd episode:The pigments of Egyptian painting.

Notebooks from Egypt, 4th episode:The modern documentation of painted walls.

Notebooks from Egypt, 5th episode:Rediscovering the monuments of eternity of Ramses II.

Notebooks from Egypt, 6th episode:Revealing pigments with light:the visible and the invisible.

Notebooks from Egypt, 7th episode:Experiencing research through images.

Notebooks of Egypt, 8th episode:Beginning of the study of the paintings of the tomb of Nebamon and Ipouky.

Notebooks from Egypt, 9th episode:A tomb shared by two artists under Amenhotep III.

Notebooks from Egypt, 10th episode:What the tomb of Amenouahsou, an artist from ancient Egypt, reveals.

Notebooks from Egypt, 11th episode:Strange uses that have been made of Egyptian mummies.

Notebooks from Egypt, 12th episode:"Why don't all the artists come here?"

Notebooks of Egypt, 13th episode:Why did the Egyptians draw the characters in profile?

Notebooks from Egypt, 14th episode:Observing craft practices in Egyptian tombs.

Notebooks from Egypt, 15th episode:About Egyptian perfumes.

Notebooks from Egypt, 16th episode:The colors of the Egyptian palette.

Notebooks of Egypt, 17th episode:The Egyptian language does not know a word to designate "art".

Notebooks of Egypt, 18th episode:The day of a scientific mission in Egypt.