Geohistorian, professor emeritus at Paris-Diderot University, Christian Grataloup has been deciphering major events on a planetary scale for many years. This global history specialist reacts to the Covid-19 crisis, the first pandemic of the 21 e century.

Christian Grataloup, specialist in global history, professor emeritus at the University of Paris-Diderot.

Christian Grataloup, is professor emeritus at Paris-Diderot University, specialist in global history. Winner of the 2007 Ptolemy Prize, he is recently the author of The World Historical Atlas (2019).

Sciences et Avenir:What was your first reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic?

Christian Grataloup: First the immediate awareness of the event, of those of which we know that we will be able to say where we were and what we were doing when it happened. No matter where in the world they take place. Thus the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in the United States or November 13, 2015 in Paris and Saint-Denis or July 14, 2016 in Nice. These events concern us directly, affect us morally and politically even if we have not all been threatened simultaneously in our physical integrity. This is not the case with the Covid-19 pandemic where the threat insinuates itself directly into everyone's daily life. Every act, even the most banal, can thus become dangerous, even fatal. We know from the outset that this period – whose beginning can be located but whose end fades into vagueness – will remain “in the history books ". In this sense, the rhetoric of war is not an excessive metaphor. A society living under the risk of snipers or bombardments, as was the case in Beirut (Lebanon) or Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina) among others, is in a comparable situation, with the notable difference that war is obviously eminently more brutal. The parallel ends here because a military conflict has strictly societal causes, without biological factors.

What inspires you about the rapid global spread of this pandemic?

Speed is the second striking characteristic. That of the spread of the disease but also that of "real time" information, including information concerning scientific research. Of course, specialists will retrospectively analyze the speed of transmission of the virus by air transport and its spread from China to Italy will remain a textbook case. I am also struck by the fact that the route taken by the coronavirus is the same as that taken by the black plague that ravaged Europe in the 14th century. Admittedly, the initial focus of this great medieval pandemic is still debated, but it must have been somewhere in Central Asia or in the Himalayan foothills. And it is already China which, from the 13th century, was the first region most massively affected. Then the fleas carrying the bacillus Yersinia pestis traveled along the Silk Roads, carried by rats, men, fabrics or furs.

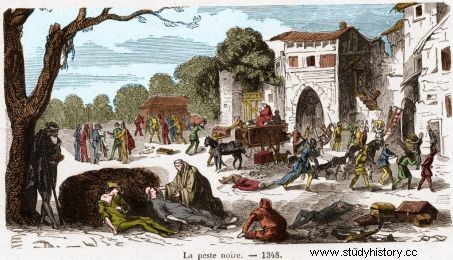

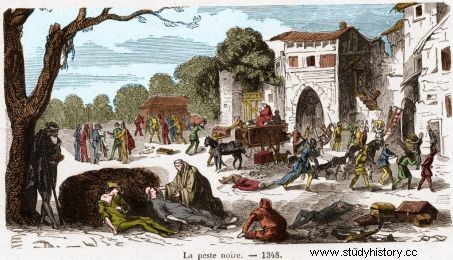

The Black Death in 1348, engraving from Histoire de France en Cent tableaux, by Paul Lehugeur, 1891. ©Leemage/AFP

It took a long time for them to affect the army of the Golden Horde besieging in 1346 the Genoese place of Caffa, on the shores of the Black Sea. The Mongols then contaminated the Italians by throwing corpses over the city walls, a simple mode of bacteriological warfare. The Genoese then fled and the bacillus with them which could thus contaminate Constantinople and, from there, all the Middle East then the coast of East Africa. In 1347, Messina and Genoa in Italy were affected, and then all of Europe. Italy was then the western terminus of the Silk Roads.

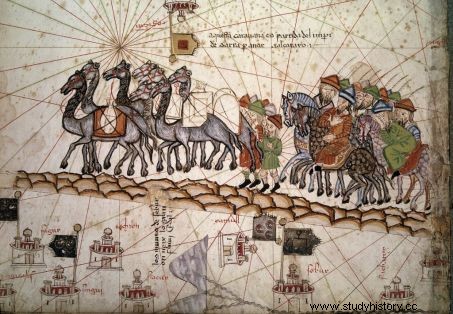

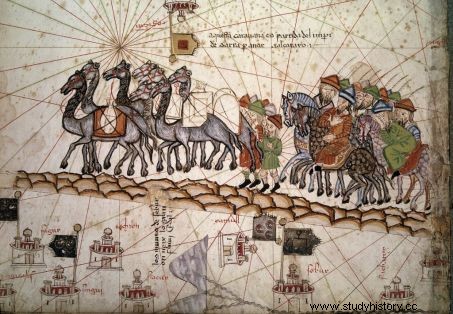

Detail of a 13th century nautical chart (portulan) showing a caravan on the Silk Road. © Leemage/AFP

This infectious journey from East to West in the Old World was certainly not the first – let us recall the dramatic episodes of the so-called Justinian plague, from the 6th to the 8th century – nor the last:the cholera pandemics of the 19th century, whose the President of the Council in office Casimir Périer was a victim in 1832, left the valley of the Ganges. Then, with the connection of American societies to the Old World after Christopher Columbus, the circuits became more complex. As early as 1493, we saw the spread of American syphilis, which began in Spain, spread throughout Europe via Italy (which the French called "le mal de Naples"), before reaching the whole world. The so-called "Spanish" flu in 1917 will start from the United States.

Are there intrinsic behaviors in certain nations?

Christian Grataloup, is professor emeritus at Paris-Diderot University, specialist in global history. Winner of the 2007 Ptolemy Prize, he is recently the author of The World Historical Atlas (2019).

Sciences et Avenir:What was your first reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic?

Christian Grataloup: First the immediate awareness of the event, of those of which we know that we will be able to say where we were and what we were doing when it happened. No matter where in the world they take place. Thus the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 in the United States or November 13, 2015 in Paris and Saint-Denis or July 14, 2016 in Nice. These events concern us directly, affect us morally and politically even if we have not all been threatened simultaneously in our physical integrity. This is not the case with the Covid-19 pandemic where the threat insinuates itself directly into everyone's daily life. Every act, even the most banal, can thus become dangerous, even fatal. We know from the outset that this period – whose beginning can be located but whose end fades into vagueness – will remain “in the history books ". In this sense, the rhetoric of war is not an excessive metaphor. A society living under the risk of snipers or bombardments, as was the case in Beirut (Lebanon) or Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina) among others, is in a comparable situation, with the notable difference that war is obviously eminently more brutal. The parallel ends here because a military conflict has strictly societal causes, without biological factors.

What inspires you about the rapid global spread of this pandemic?

Speed is the second striking characteristic. That of the spread of the disease but also that of "real time" information, including information concerning scientific research. Of course, specialists will retrospectively analyze the speed of transmission of the virus by air transport and its spread from China to Italy will remain a textbook case. I am also struck by the fact that the route taken by the coronavirus is the same as that taken by the black plague that ravaged Europe at 14 th century. Admittedly, the initial focus of this great medieval pandemic is still debated, but it must have been somewhere in Central Asia or in the Himalayan foothills. And it was already China which, from the 13 th century, was the first region most massively affected. Then the fleas carrying the bacillus Yersinia pestis traveled along the Silk Roads, carried by rats, men, fabrics or furs.

The Black Death in 1348, engraving from Histoire de France en Cent tableaux, by Paul Lehugeur, 1891. ©Leemage/AFP

It took a long time for them to affect the army of the Golden Horde besieging in 1346 the Genoese place of Caffa, on the shores of the Black Sea. The Mongols then contaminated the Italians by throwing corpses over the city walls, a simple mode of bacteriological warfare. The Genoese then fled and the bacillus with them which could thus contaminate Constantinople and, from there, all the Middle East then the coast of East Africa. In 1347, Messina and Genoa in Italy were affected, and then all of Europe. Italy was then the western terminus of the Silk Roads.

Detail of a nautical chart (portulan) of the 13 e century, depicting a caravan on the Silk Road. © Leemage/AFP

This infectious journey from East to West in the Old World was certainly not the first – let us recall the dramatic episodes of the so-called Justinian plague, from the 6 e at 8 th century–nor the last:the cholera pandemics of the 19 th century, of which the President of the Council in office Casimir Périer was a victim in 1832, set out from the Ganges valley. Then, with the connection of American societies to the Old World after Christopher Columbus, the circuits became more complex. As early as 1493, we saw the spread of American syphilis, which began in Spain, spread throughout Europe via Italy (which the French called "le mal de Naples"), before reaching the whole world. The so-called "Spanish" flu in 1917 will start from the United States.

Are there intrinsic behaviors in certain nations?

Today, the ecumene [the inhabited world] is constantly strained between local societies and the global level. This dilemma is politically translated between globalism and sovereignty. However, the characteristic of a pandemic, like a cloud of pollution, is to ignore any geopolitical border. No Chinese wall will ever stop the hordes of the virus! However, each society reacts in its own way... and in a dispersed order. The authority of the WHO remains purely informational. It was restrained from the start of the epidemic by Chinese diplomacy, then undermined by US budget cuts in the midst of the crisis. European "solidarity", well undermined, seems to be one of the most important collateral victims of the coronavirus. As a result, the collective particularities are clearly expressed since all societies today have to solve exactly the same problem, with modest chronological shifts and, perhaps, differences linked to climatic environments. Overall, the role of the State has been revalued, the reaction of very liberal governments (the United States, the Netherlands, Brazil, etc.) being much slower than that of more Colbertist countries such as France - despite wavering management - but with the necessity of having to regulate less respect for collective decisions. Thus, it appears that the clearest opposition seems to be taking shape today between holistic societies and individualistic societies, to use a classic sociological grid. The Chinese power is also trying to transform it into a pro-authoritarian regime propaganda theme. However, it is above all the collective social behaviors that are striking, more than the political regimes:the democratic states of South Korea or Taiwan have not had very different responses from those of the Chinese single party or authoritarian democracy. Singaporean. Conversely, politically and economically liberal societies, most often marked by Protestantism (Northern Europe, United Kingdom, United States), tended, at least at the beginning of the crisis, to give way to a "natural vaccination" , a sort of law of the healthcare market, even if it means risking high mortality.

What does history say about "post-epidemiological crisis" behavior?

First, the behaviors we see during the crisis we are going through are very similar to those associated with past pandemics. Just read Fear in the West by Jean Delumeau (Fayard, 1978) to see that refuge in the irrational is a constant. The slightest hope of a miracle makes us forget the slightest common sense and any critical spirit. Thus, the prescription of hydroxychloroquine may be useful in certain cases in the face of Covid-19, but is obviously not a panacea, judging by the debate between scientists. We can therefore imagine that the "day after" will have common features with what followed for other epidemics. So let's plan for months, even a "crazy" year, like after the cholera epidemic that killed 19,000 Parisians in particular in 1832-1833.

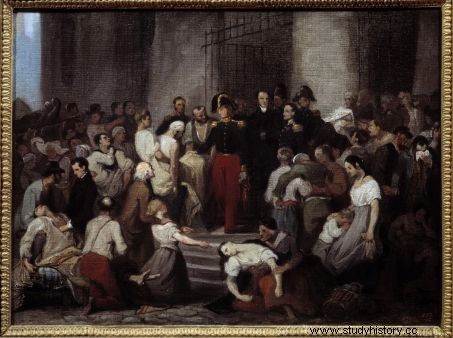

Painting by Alfred Johannot (1800-1837), showing the Duke of Orléans visiting the sick at the Hotel-Dieu during the cholera epidemic in Paris, in 1832. ©Leemage /AFP

1834 was a frenzy of boulevard life! The theaters had never been so full, the café terraces even more crowded than before, with the expression of a consumerist fever, an appetite for all possible encounters as long as they were "in real space" as we say "in real time". We also expect that the lessons of the Covid-19 crisis will hardly be learned, except for minor aspects. We will undoubtedly stock up on masks, but we will quickly forget the basic questions, the languorous illnesses of hospitals or the necessary solidarity between neighboring nations, in particular those of the European Union. The plague – and the fear that followed from it, both endemic in 15 e Europe -18 e century – had many walls and lean-tos built on the borders, often with the opposite effect of the desired prophylaxis. It is even more likely that, quickly obsessed with managing the economic repercussions, we will not strengthen any international cohesion. And it will quickly be forgotten that a pandemic is necessarily global, even if we unravel a few stitches in the multinational production chains.