Joseph Fouché was a French revolutionary and politician, Minister of Police under the Directory, the Consulate and then the Empire. Balzac saw in him a “singular genius”:Fouché , the chameleon, the man of all paradoxes, feared by Robespierre, the friend and the enemy, feared but admired by the consul then emperor Napoleon. If the execrations and imprecations of which he was the object were plethoric, however he remained for a very long time close to power, skillfully handling tricks and perfidy. Crossing, not without firing a shot, the Revolution and the Empire, resisting when the greatest fell, it was as he had liked to live, in the shadows, that he died, forgotten by all, he, Napoleon's minister, the rifleman of Lyon and one of the killers of the "Incorruptible" of Arras.

Joseph Fouché was a French revolutionary and politician, Minister of Police under the Directory, the Consulate and then the Empire. Balzac saw in him a “singular genius”:Fouché , the chameleon, the man of all paradoxes, feared by Robespierre, the friend and the enemy, feared but admired by the consul then emperor Napoleon. If the execrations and imprecations of which he was the object were plethoric, however he remained for a very long time close to power, skillfully handling tricks and perfidy. Crossing, not without firing a shot, the Revolution and the Empire, resisting when the greatest fell, it was as he had liked to live, in the shadows, that he died, forgotten by all, he, Napoleon's minister, the rifleman of Lyon and one of the killers of the "Incorruptible" of Arras.

Joseph Fouché, an ambitious young man

Near Nantes, in the 36th year (1) of the reign of the "Unloved" Louis XV, Joseph Fouché was born on May 31. Son of a sailor, one would have hoped that the young man would embark on a maritime career but nothing helped, Joseph not having this paternal inclination for the sea. He therefore began his intellectual training with the Oratorians, introduced in France in the early years of the regency of Marie de Medici by Cardinal de Bérulle. A few years later, it was as a mathematics teacher that we found Joseph Fouché at the Oratory.

The student had become a teacher and already seemed to be interested in politics, albeit still from afar, when he met in Arras a young lawyer still unknown in the kingdom, Maximilien by Robespierre. A friendship began which bound the two men. Joseph even failed to become her brother-in-law, an idyll having been born between him and Charlotte de Robespierre. But strangely, Fouché cut short this project and put an end to it, for a reason which is unknown to us. Perhaps it was from this refusal that the disagreement between the two men was born, the same people who soon found themselves opposed to the Convention, Fouché being in the ranks of the Girondins, Robespierre in those of the Montagnards.

What must have been Fouché's indisposition and boredom to choose, on this January 16, 1793, the life or death of the king in the company of several hundred other deputies . However, it was necessary to choose and, on the proposal of the Arras lawyer, to publicly express his choice. The names of the voters and their choice were to be published the next day in Le Moniteur Universel. Fouché once again followed the majority – he always followed the majority, which was the only party, as Stefan Zweig showed very well, to which he remained faithful all his life – and in particular the choice of Vergniaud, leader of the Girondins, who had chosen the king's death. Five days later, the bloody head of Louis XVI finally fell under the cutting power of the "national razor".

Fouche in the tumult of the French Revolution

Soon, the Convention asked 200 delegates, including Fouché, to restore order in France and avoid , by their presence, possible uprisings. They were endowed with full powers, which were not however unlimited, the Committee of Public Safety watching over abuses. This is why Fouché acts as a “terrorist of speech”. He restores order without ever spilling, unlike Jean-Baptiste Carrier in Nantes, the slightest drop of blood.

Soon, the Convention asked 200 delegates, including Fouché, to restore order in France and avoid , by their presence, possible uprisings. They were endowed with full powers, which were not however unlimited, the Committee of Public Safety watching over abuses. This is why Fouché acts as a “terrorist of speech”. He restores order without ever spilling, unlike Jean-Baptiste Carrier in Nantes, the slightest drop of blood.

Until the day the Convention instructed Collot d'Herbois and Fouché to sound the death knell for the anti-revolutionary agitators in Lyons who dared to defy the authorities by having them executed, despite the protests and threats of the Convention, Chalier, a former priest who had become one of the greatest followers of the Revolution in France. The two men arrived in Lyon in November 1793. The tone was set by Fouché during a celebration given in honor of Chalier where he exclaimed:"The blood of scoundrels is the only lustral water that can appease your spirits" .

The word announced the action that followed:in the Brotteaux plain, nearly 2,000 people released from Lyon prisons were mercilessly executed. But suddenly, Fouché remembered that the Committee of Public Safety was watching:a shift in convictions occurred, the number of daily convictions falling very considerably. However, Fouché knew that he was threatened. Robespierre glared at him and Fouché realized that, if he wanted to save his head, he had to first knock off his enemy's.

On 18 Prairial Year II, he had the audacity to get himself elected president of the sacrosanct club of the Jacobins. Robespierre was furious. For the first time, he understood what kind of opponent he had against him. A fight ensued which saw Fouché's victory. On the night of 8 to 9 Thermidor indeed organized Fouché, in the company of other people opposed to Robespierre such as Tallien and Barras, to bring down the latter, and; on 10 Thermidor, after two days of imbroglio, Robespierre was guillotined on the Place de la Révolution (2).

In the shadow of power

From 1795 to 1798, Fouché experienced a voluntary exile which consisted in escaping the acts of terrorism of which he was accused. He lived in misery, content to vegetate, and no longer receiving any income. Henceforth, Fouché recognized that money had a flavor, a flavor that he blamed a few years earlier in Lyon. At the same time, the few friends Fouche had left him. Only one politician still cared about him and visited him fairly regularly, Barras, for whom he became a spy.

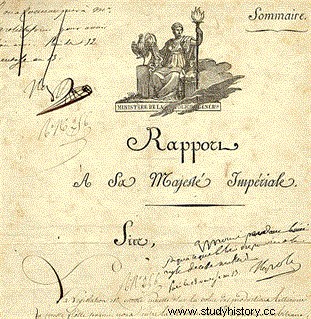

To everyone's surprise, on 3 Thermidor Year VII, Fouché was brought out of the shadows by an appointment as head of the Ministry of Police. This "Hoover" (3) of the end of the 18th century knew a lot more than the Directory. He had discovered the secrets of politicians, and thereby held them in his hands. So he was informed by Joséphine de Beauharnais, with whom he had an epistolary relationship, of Bonaparte's return. He participated actively but discreetly in the coup d'etat of 18 Brumaire by allowing its good success. He could have, moreover, if he had obviously wanted to, to defeat the conspiracy by notifying Barras.

After Napoleon seized power, he appointed him, as Fouché had foreseen and hoped, Minister of the Police. But, being too powerful, Napoleon later got rid of him by suppressing his function and giving him a seat in the Senate in compensation, certainly a bitter pill for Fouché, as well as the senatorship of Aix, which allowed him to enrich himself considerably. and soon to become France's second fortune. But this exile had a much tastier taste than the previous one. In fact, Fouché had exchanged his old hovel for a magnificent residence on rue Cerutti.

After Napoleon seized power, he appointed him, as Fouché had foreseen and hoped, Minister of the Police. But, being too powerful, Napoleon later got rid of him by suppressing his function and giving him a seat in the Senate in compensation, certainly a bitter pill for Fouché, as well as the senatorship of Aix, which allowed him to enrich himself considerably. and soon to become France's second fortune. But this exile had a much tastier taste than the previous one. In fact, Fouché had exchanged his old hovel for a magnificent residence on rue Cerutti.

But the character hardly aspired to a luxurious life. His only desire was to embrace power. He was reassured and triumphed internally when Napoleon, surely judging him indispensable, reappointed him Minister of Police in 1804. Later, the Spanish campaign, which began in 1808, saw the rapprochement of two enemies of yesterday, Talleyrand and Fouché, dog and cat, who had the common point of disapproving her; which necessarily made Napoleon fear that a plot was hatched by the two characters. He expressed his furious anger at Talleyrand in a phrase that later became famous:"You're shit in a silk stocking" (1809).

Fouche, audacious and zealous Minister of Police

The Duke of Périgord was also stripped of his title of chamberlain, but Fouché once again remained in place:"We remember it:Collot, his accomplice in the machine-gun fires of Lyons, is deported to the Iles de la Fever, while Fouché remains; Babeuf, his partner in the fight against the Directory, is shot, Fouché remains. His protector Barras is forced to flee, Fouché remains. And this time too, the man in the lead, Talleyrand, is the only one to fall, Fouché remains" (Fouché, Zweig).

When he learned of the English landing on the island of Walcheren on August 31, Fouché wanted to show that he was a competent man and he summoned the National Guards. During this time, the emperor, on campaign, knew nothing of all these measures which were taken in his absence. Audacious, Fouché appointed Bernadotte, the general hated by Napoleon, chief of the provisional army. The English were defeated. Napoleon I applauded Fouché's saving audacity. But the latter, surely intoxicated by the recent triumph, made the mistake of raising National Guards again, this time with no apparent danger looming on the horizon.

Although he had been appointed Minister of the Interior, in addition to his post as Minister of Police, Fouché had to relinquish this ministry. But Napoleon, in return, decided to ennoble Fouché on August 15, 1809 in Austria and made him Duke of Otranto (region in southern Italy). Fouché repeated in error. He tried to negotiate peace with the English, in the name of the emperor, who obviously knew nothing about it. Fouché was immediately revoked and Napoleon appointed Savary, Duke of Rovigo, Minister of Police in his place.

Ungratefully appointed French ambassador to Rome, Fouché took revenge by destroying the files he had compiled at the ministry and more generally annihilating the laborious work he had provided for several years . After 1810, Fouché began his third exile in his very comfortable senatory in Aix. In these difficult times, he lost his wife who had been so faithful to him and who had given him several children, two of whom had died in infancy. After his escape from the island of Elba, Napoleon reconnected with Fouché by appointing him, for the third time, Minister of Police. But the interlude was short, and Napoleon fell quickly. There followed a short period during which Fouché had power after having duped Carnot, but strangely, he proposed to the Count of Provence, brother of Louis XVI, to give him the reins of power in exchange for a place in his government. At the end of July 1815, it was done.

From hated man to forgotten man

Very fragile place of Minister of Police than that which had been swapped by Fouché. The Bourbons never forgot that he had once voted for the death of Louis XVI. Within the royal family, the most virulent opposition came from the Duchess of Angoulême, daughter of the deceased king and Marie-Antoinette, who – understatement – hated this individual who only inspired her with disgust and hatred. So the other members of the royal family easily convinced the king, now fully installed in power, to remove Fouché. It was the one who was ironically nicknamed "the lame devil", Talleyrand, who made sure to make him understand that his presence was now disturbing. The duper had finally been played. While he had given them the power when he himself held it, he was deprived of the function for which he had worked so hard, while assuring him, as a sad thank you, a post of ambassador to the court of Dresden.

Very fragile place of Minister of Police than that which had been swapped by Fouché. The Bourbons never forgot that he had once voted for the death of Louis XVI. Within the royal family, the most virulent opposition came from the Duchess of Angoulême, daughter of the deceased king and Marie-Antoinette, who – understatement – hated this individual who only inspired her with disgust and hatred. So the other members of the royal family easily convinced the king, now fully installed in power, to remove Fouché. It was the one who was ironically nicknamed "the lame devil", Talleyrand, who made sure to make him understand that his presence was now disturbing. The duper had finally been played. While he had given them the power when he himself held it, he was deprived of the function for which he had worked so hard, while assuring him, as a sad thank you, a post of ambassador to the court of Dresden.

But it is true that "power is, according to Zweig's beautiful phrase, like the head of Medusa:he who has seen its face can no longer take his eyes off it ". While it would have been less dishonouring to refuse this office, Fouché nevertheless accepted it, thus contributing to nourishing the contempt he already aroused in many people. It was well and truly over for the great respected and feared minister. We thanked him by isolating him outside France. As he was being driven to Dresden, Joseph Fouché, an intelligent man if ever there was one, must have realized that the exquisite sweetness of power was dead.

All his life he had chosen to stay close to this one while purposely remaining in the shadows. This time, the shadow, his most faithful companion, accompanied him while power abandoned him. Bitter exile for this aging man, who had married in the last years of his life with a great aristocrat, the Comtesse de Castellane, after he lost his wife and became a widower.

Transhumant from court to court, despised in each, hated in Prague, he finally obtained to end his days in Trieste in 1820, in a warm and sunny place, on the edge of the Adriatic. However, he could not really take advantage of the benefits of the climate and end his life peacefully. In fact, weren't rumors claiming that the Countess of Castellane, his wife, knew an idyll with a young man named Thibaudeau?

Fouche died the day he was ousted from power. Since 1815 Fouché was no more. Five years had sufficed to bring down the man whom so many people had wanted to see dead and it was on December 26, 1820, after a singular life in every respect, that the said Fouché expired, forgotten by all. From the Oratory to atheism, from communist discourse to France's second fortune, this man with a pale complexion, who showed no emotion on his face, was one of those elusive individuals, with a surprisingly complex personality, certainly terrifying. but fascinating.

Bibliography

- ZWEIG Stefan, Fouché, Paris, Le Livre de Poche, 2000, 284p.

- TULARD Jean, Joseph Fouché, Paris, Fayard, 1998, 496p.

- CASTELOT André, Fouché, the double game , Paris, Perrin, 1990, 423p.

1) Louis XV, although king since 1715, was under the tutelage of the regent Philippe d'Orléans until 1723.

2) The current Place de la Concorde.

3) John Edgar Hoover, famous boss of the FBI for several decades, who shared with Fouché the common point of being feared by all because of the secrets he knew.

Katholieke University Leuven