Was Babylon really the most licentious capital in the history of the ancient world? Venereal complaints of the inhabitants say too much ...

Babylon, the capital of Babylon in the Tigris-Euphrates basin, reached the peak of its wealth and influence around 1750 B.C.E. However, it was not remembered as a cultural center and center of a mighty empire. Babylon went down in history primarily as a hotbed of debauchery. This is how both ancient and medieval Christians imagined him. But that was also how Babylon was perceived in neighboring countries during its heyday. The goddess Ishtar contributed primarily to the town's bad reputation. Or to be more precise:her extremely peculiar cult.

Holy sex

The Babylonians believed that Ishtar sanctified fleshly love in almost every form. In their opinion, sexual intercourse performed for her glory was supposed to provide a person with youth and vitality. The goddess did her best not only over people. According to the ancient Epic of Gilgamesh , she celebrated the new year in the arms of gods and mortals, but also in the arms of lions and horses.

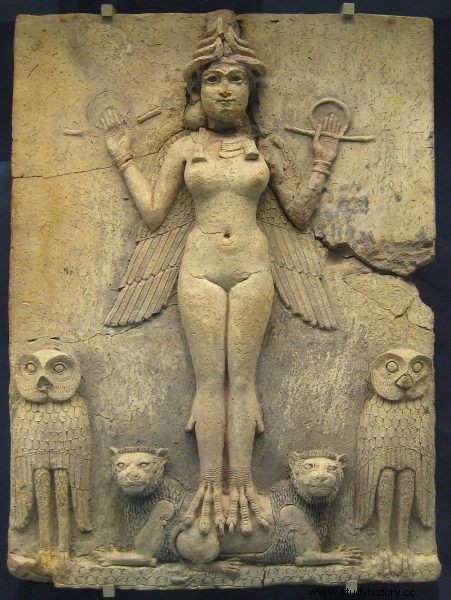

The sculpture, now in the British Museum, probably depicts Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of love and sex. It was her cult that contributed to the excessive sexual debauchery for which the Mesopotamian capital of Babylon is famous.

She was to be imitated by specially trained priestesses and temple maids, about whom it was loud in almost the entire ancient world. They served their mistress, but also pilgrims coming both from Babylon and from neighboring or even very distant countries.

The worship of the goddess Ishtar, however, was not limited only to the temple space. Any Mesopotamian woman wishing to devote herself to or worship the female deity of ancient Babylon had to fulfill a "sacred duty."

One of the most famous Greek travelers and historians, Herodotus, wrote about him:

Every woman of this country must visit the temple of Aphrodite once in her life [Ishtar] give himself to a stranger (...) sitting in the sacred circle of the temple (...).

Later discoveries by historians completed the application of Herodotus. "Every woman" actually meant young married women who could return to their lawful husband only after having had sexual intercourse with a stranger. In turn, according to other sources, girls were subjected to the obligation even before the wedding. It was to provide them with the goddess's consent to get married. Temple sex, therefore, had in Babylon not only rejuvenating properties but also the power to sanctify the wedding. But what were the effects of making sexual acts sacred?

Sex is not only holy

Disease was the main consequence. Yet, paradoxically, sexually transmitted ailments, which spread through universal sexual freedom, were considered punishments of the goddess. Ishtar sent her to the wicked who did not obey divine or human laws.

(...) severe disease, demon [disease] bad, a painful wound that will not heal [and whose] essence [no] the doctor will not recognize nor the dressing [her] won't heal, [nor] just as he will not remove the kiss of death, let him cause it in its limbs, and as long as life smolders with him, let him despair in his masculine strength. (…)

Hammurabi ruled in 1792-1750 BCE and was the most famous king of the 1st dynasty of Babylon. On the preserved fragment of the stele, the sun god Shamash gives him symbols of royal power. He went down in history primarily as the creator of the Code, from which the famous principle of "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth" is allegedly derived.

Thus, King Hammurabi cursed all those who disobeyed his orders at the end of his famous Codex. However, venereal diseases did not only affect the disobedient. And not only in the temples it was possible to get infected with them. As Jürgen Thorwald explains in Ancient Medicine. Its secrets and power , also secular prostitution was practiced on an enormous scale.

Clay boards reveal that wenches were harassing customers in the street, in plazas, in the fields, and in the garden. In addition to them, there were also "kulu", male prostitutes who offered their services to both women and men. Eunuchs, as well as non-castrated slaves, were dragged into homosexual intercourse.

Unholy ailments

Historians are divided on the prevalence of syphilis in ancient Babylon. According to one theory represented by researchers such as Henrich von Haeser ( Lehrbuch der Geschichte der Medizin 1875-1882) or Ethne Barnes, syphilis was present throughout the ancient world. Others, including Hans Zinsser and Jürgen Thorwald they claim that the disease developed in America during the "Columbus Age" and from there it spread to other parts of the world. Today more and more scientists and researchers of ancient diseases are leaning towards the latter thesis.

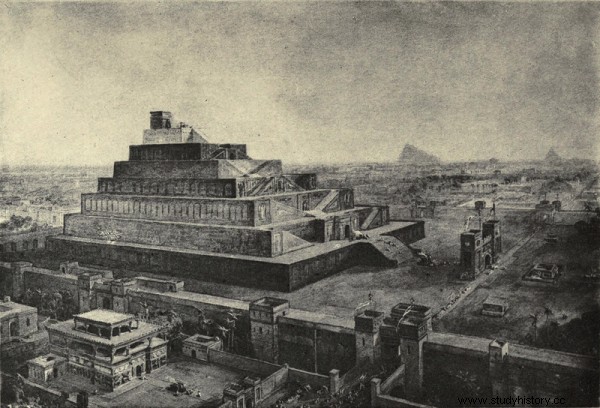

Babylon as illustrated by William Simpson. The author was inspired by the nineteenth-century archaeological discoveries in one of the most promiscuous capitals in history ...

The clay tablets preserved to this day, however, bring irrefutable information about other sexual ailments consuming the Babylonians. We have almost all possible inflammations of the intimate passages here. In the book Ancient Medicine. Its secrets and power we find the following accounts from the Mesopotamian records:

If a man loses his semen while sleeping or walking (...) and his penis and clothes are full of semen (...) and then - when blood flows from the man's penis or oil…

... it was the man who was touched by 'the hand of Ishtar'. The disturbing color of the urine revealed another sexually transmitted disease, gonorrhea:

If a man's urine looks like donkey urine (...) [or] if a man's urine looks like brewer's yeast, the man suffers from gonorrhea.

Is the fall of Babylon immortalized in one of the woodcuts of the Nuremberg Chronicle (15th century) a punishment for excessive sexual debauchery?

Not only male ills are immortalized on clay tablets. In the collective work Diagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine we find the translation of another preserved record:"If the semen of a woman or a man leaks while urinating, the man or the woman suffers from a venereal disease."

But Babylon knew how to deal with it, or so the medics of the time said. The bronze tube called "upu" was the key through which the medicine was introduced into the penis. Thus, the catheter popular today turns out to be an invention of the ancients. And who would have thought that excessive licentiousness would bring a tool that would have revolutionary significance in world medicine? Perhaps this is how Ishtar blessed her worshipers.

Bibliography:

- Barnes Ethne, The dead do tell tales [in:] Corinth, The Centenary 1896-1996. Vol XX , edit. by Charles K. Williams, Nansy Bookidis, The American School of classical studies at Athens 2003.

- Bednarczyk Andrzej, Medicine and philosophy in antiquity , University of Warsaw. Faculty of Philosophy and Sociology, Warsaw 1999.

- Sexually transmitted diseases:collective work , edited by Tomasz F. Mroczkowski, Wydawnictwo Czelej, Lublin 2012.

- Herodotus, History , trans. Seweryn Hammer, ed. Romuald Turasiewicz, National Institute for them. Ossoliński, Wrocław 2005.

- Hammurabi Code , trans. Marek Stępień, Alfa-Wero Publishing House, Warsaw 2000.

- Nemet-Nejat R. Karen, Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia , Greenwood Press, London 1998.

- Niżnikiewicz Jan, Secrets of ancient medicine and magic , Tower Press, Gdańsk 2003.

- Pryke M. Louise, Ishtar , Routledge, London-New York 2017.

- Scurlock A. Jo, Andersen R. Burton, D iagnoses in Assyrian and Babylonian Medicine:Ancient Sources, Translations and Modern Medical Analyzes , University of Illinois Press 2008.

- Stephen Bertman, Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia , Oxford University Press, New York 2003.

- Thorwald Jürgen, Ancient Medicine. Its secrets and power. Egypt, Babylonia, India, China, Mexico, Peru , trans. Albin Bandurski, Janina Szczaniecka, Wydawnictwo Literackie, Krakow 2017.

- Zinsser Hans, Rats, Lice and History , Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick-London 2008.