Bolesław the Brave was called a beer drinker. Queen Jadwiga drank over two liters of the brewery a day. Zygmunt Stary started the day with a beer soup and ended with two solid mugs. Did Poles have a stronger head in the past?

Beer has always accompanied our ancestors. In the "Chronicle of Poland" Gall Anonim tells the story of two mysterious guests, as it turned out, sent from heaven, who visited Piast Kołodziej. The poor man wanted to be a good host, so he offered them a barrel of well-fermented beer, which he kept for his only son's haircut.

Another famous medieval chronicler, Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg, also expressed his appreciation for Polish beer:Bolesław the Brave was to treat Emperor Otto III with this drink during the Gniezno Congress. But reluctant to the ambitious ruler of the emerging state, they lovingly called him "Trink-Biere", that is, a beer drinker. However, Jan Kochańczyk, author of the book "Beer:a national drink", strongly emphasizes that:

[...] royal drinking did not prevent Brave from achieving his political and military goals. Beer, unlike wine, has a calming effect , it does not blur the mind quickly, nor does it knock you off your feet as quickly as booze.

Two mugs for Andegawenka

Polish rulers appreciated these values. Królowa Jadwiga, which is confirmed by the relevant bills, for a modest dinner for herself and her mansions, which took place on May 9, 1389, ordered three achteles, i.e. forty-eight liters of beer (one achtel is the eighth part of a barrel) to be ordered in Niepołomice . Usually, she drank two, two and a half liters a day, which is within the then Polish statistical average.

Zygmunt Stary, a ruler known for his moderate lifestyle, was also a beer drinker:he ate grammar for breakfast every day, i.e. beer soup, considered a fasting dish, and usually ended the evening with two mugs.

Queen Jadwiga did not despise good beer!

Perhaps the penultimate of the Jagiellons on the Polish throne drank beer for health reasons. As we can read in the book entitled “Foamed history of Europe. The 24 pints that brewed the beers of Mika Rissanen, Juha Tahvanainen, the water was usually polluted, so not only tasteless, but also dangerous. At best, it could pose a… diarrhea.

Therefore there were far fewer victims of any kind of plague than among people "condemned" to drink water. Therefore, for safety and hygiene reasons, the beer, decontaminated in the brewing process - and not water - was usually watered by the military (some say that the hop drink was the source of the success of our knighthood at Grunwald).

Yet Jędrzej Kitowicz in his "Description of customs and customs during the reign of Augustus III" mentions that doctors for various ailments prescribed beer from Grodzisk Mazowiecki (with good results), ascribing to it "the virtue of mineral waters". And to think that the latter were to return to elegant tables only in the 19th century.

Instead of bread:beer for breakfast

Nutritious beer soup, eaten instead of bread or milk for breakfast, was a "classic" of Polish cuisine even in the nineteenth century (it was mentioned by Adam Mickiewicz in the Second Book of "Pan Tadeusz").

Samuel Linde, an outstanding Polish lexicographer living at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, gave in his dictionary one of the many recipes for it:a little, there will be a grammar or a pottery . You could also add a little cinnamon, egg yolks, cottage cheese, cream.

Of course, after cooking, the taste remained in the dish, but there was almost no alcohol left . And to think that beer soup was only replaced in Polish cuisine by… strong coffee (which Mickiewicz also writes about).

Finally, it is worth mentioning one more ruler who was in love with beer - and in addition he was extremely generous:Sigismund Augustus (after all, the son of an Italian woman for whom wine was her basic drink) ordered that for the feast he gave on July 10, 1545 in Knyszyn,

A thin skin for a kid

He didn't have to worry that the fun would end soon, because drunk guests would fall under the tables. Most breweries (and there were a lot of them, in Krakow, brewers worked literally on every other street) produced very weak beer, two or three percent , in addition, with a rather unpleasant, from our point of view, tart taste, which was tried to be refined by adding a little honey.

Beer was drunk by both kings and simpletons, not to mention the clergy.

They were called "thinner" and were given - without any negative health effects - even to young children. Adults drank - rarely, because it was much more expensive - also the so-called "noble beer", equally unpalatable, but stronger.

It was only in the 17th and 18th centuries that high-quality beers, known as great snipe, gained more popularity. They were produced from high-quality wheat and barley, using crystal clear, specially filtered water. Sometimes also from oats, which after centuries becomes fashionable again among modern home brewers-amateurs.

High-quality hops were also grown - in such quantities that the supply exceeded the demand. It should be remembered that this plant began to be dried in Poland for brewing purposes much earlier than in most Western European countries.

It is true that the first mention of this topic dates back to 1255, but we know that the Slavs and Balts got to know the qualities of hops thanks to the Mongol peoples before they entered the European civilization. And we passed the knowledge about beer, that is "barley soup seasoned with hop," to the Germans.

Beer savoir-vivre

Beer etiquette also protected against drunkenness to some extent. The servant drank the first glass (for safety), then the host, and finally the guests. The foam in a mug filled with the "attic", that is, full, could be blown out no more than twice. And you weren't allowed to… dip your nose in beer.

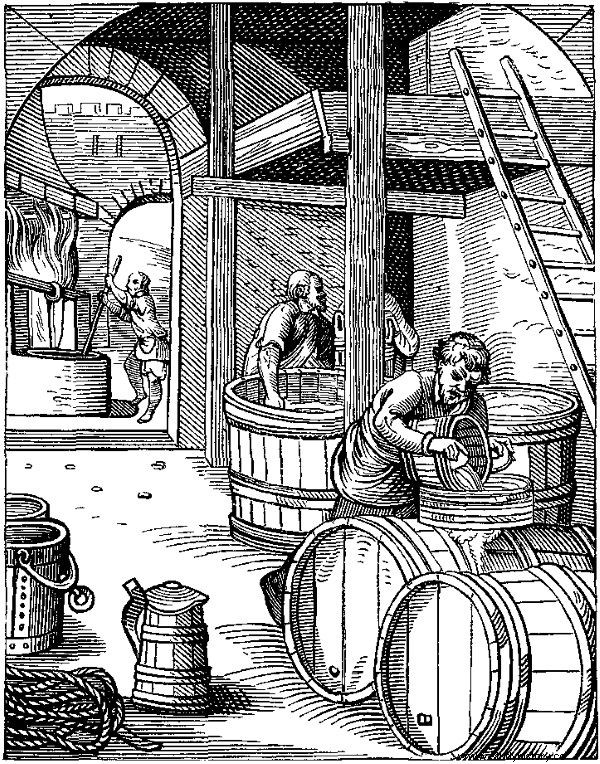

The interior of a 16th century brewery.

This label was remembered even in the lazy and lazy Saxon times. As Kitowicz writes, "One sat down at the table, the others circled him in the judges and witnesses' office, he took the glass in his hand, large or small, poured with beer; this he should have drunk not together, but in three competitions.

For the first draft of beer, he should have stroked his mustache one finger at a time, the second time, on the chin with the same finger straight into the nose from top to bottom once, under the chin in the same line once from bottom to top, hit the table with the same finger once, from the bottom once, stamp the floor once and pronounce the word :»Beer« .

Bibliography:

- Antonina Jelicz, Everyday Life in Medieval Krakow , Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Warsaw, 1966.

- Jan Kochańczyk, Beer. National drink, e-bookowo.pl, 2012.

- Mika Rissanen, Juha Tahvanainen, A foamy history of Europe. 24 pints that made beers , Agora Publishing House, Warsaw, 2017.