The libertarian slogans of democratic Athens did not extend to women. Animals and objects were seen in them. Treated as their own belongings, they had to obey all their husbands' orders. If they were raped, they were considered adulterers, if they objected, they were often put to death.

Apparently, Zeus created female sex for the destruction of mankind, and the first woman - Pandora - has already proved it. As a dowry, she got a barrel, from which, together with her husband, she released all misfortunes and diseases into the world. The myth about Pandora's box is well known to this day. And it is interesting that, in fact, the story of Eve, Adam and the forbidden fruit of the paradise apple tree differs so little from it ...

As emphasized in her publications by prof. Lidia Winniczuk, a classical philologist, on whose books generations of lovers of antiquity in Poland were brought up, the situation of women in the Greek world has changed quite radically over the centuries. In fact, known from "The Iliad" and "The Odyssey", they were not prisoners of men, they made informed decisions, had a real impact on power.

Helena Trojańska walked the streets of the city, giving everyone the opportunity to admire her beauty. In the time of the Athenian democracy, however, she would be taken for a whore. Not to mention that no one would start a war because of her, and no husband would forgive her for treason.

At the news that King Priam was listening to the advice of his wife Hekabe, and that Hector was in serious talks with Andromache, the Athenians in Pericles would burst out laughing. The feudal princess Nauzykaa would pay for her forbidden conversation with the stranger - the shipwrecked Odysseus - a few centuries later at home with a solid spanking, and perhaps a loss of honor.

"Pandora" by John William Waterhouse (1896). Not only in the Bible, but also in Greek mythology, women are considered the source of evil and misfortune.

It seems that even if the men in Homer's works rank romance after romance (for example, the aforementioned Odysseus), women occupy a privileged place in his epics. Or at least it seems so, because in the period after Homer, in the era of unquestionable power of men who, after centuries, feminists called phallocracy they didn't have much to say. Women were then treated as eternal children who needed constant supervision.

Fallocracy over the top

According to the regulations of the Athenian legislator Solon (7th-6th centuries BCE), they were kept away from strangers. Similar laws have been introduced in many other city-states. Men and women lived in isolation; even in the shared house, wives had separate rooms and slept with their children more often than with their husbands. Outside, their contacts were limited. The Athens women agreed because in a world where even rape victims could be treated as adulteresses, isolation guaranteed them at least relative safety.

Family fathers kept an eye on their daughters. 4th century BC Greek orator and politician Aeschines told the story of a parent who, learning that his daughter had been seduced and lost her virtue before marriage, bricked her alive in an empty building. Not alone, but with ... a horse. The father hoped that the animal would kill the young woman in time. Aeschines assured that the foundations of this house can still be found and are called "the girl's place."

Is it just an ancient urban legend? Not necessarily. With an unmarried daughter who lost her virginity, a father could do anything:even beat him or sell him into slavery . After all, marriage was a question of dowry and agreement between parents, not of fascination between lovers. Seducers of unmarried women were sometimes forced to marry. But what if the lover was already married? A virgin who inadvertently lost her virginity in this way saved herself as much as she could. For example, she advised the maid what to do to hide this fact until the wedding night and continue to appear immaculate to the groom.

The philosophers of the time wrote that the place of self-respecting Athena is her home - as long as she did not open its door personally, because then she would turn it into a brothel. For comparison, in the same 5th century B.C.E. in Sparta, competing with Athens, married women not only did not have to hide their faces from strangers and spend most of their lives in a women's room, but they walked freely on the street, competed in physical exercises, and they scandalized Greeks from more severe lands by "flashing their thighs" or even showing themselves naked . But even in Sparta, the world of women and the world of men were separate.

Not for women the games

The domain of a typical Athena was the household; they did not go to feasts. It is not even certain whether they could watch theatrical performances, although many of the plays spoke of them. "No wonder that among the (how few) famous Greek women there is not a single Athena:Sappho came from the islands of Lesbos, Corinna and Mirtis (poets rivaling Pindar) from the cities of Boeotia, and Aspasia (a longtime companion and finally wife of Pericles) from Miletus, a city on the coast of Asia Minor "- notes the classical philologist Inga Grześczak in her sketches.

Good ladies did not travel; "Common" Greek women could not even participate in the famous Olympics. At best, they had their own, less important competitions. Only some priestesses appeared in Olympia, and rich owners of chariots participating in the competition participated "in absentia". Thus, the Spartan princess of Kyniska became the first woman to win the Olympic laurels in 396 BCE. But when eight years later Kallipatejra of Rhodes disguised herself as a man to see her son fight, and was exposed, she faced the death penalty . She was only spared because of the merits and Olympic triumphs of her family members.

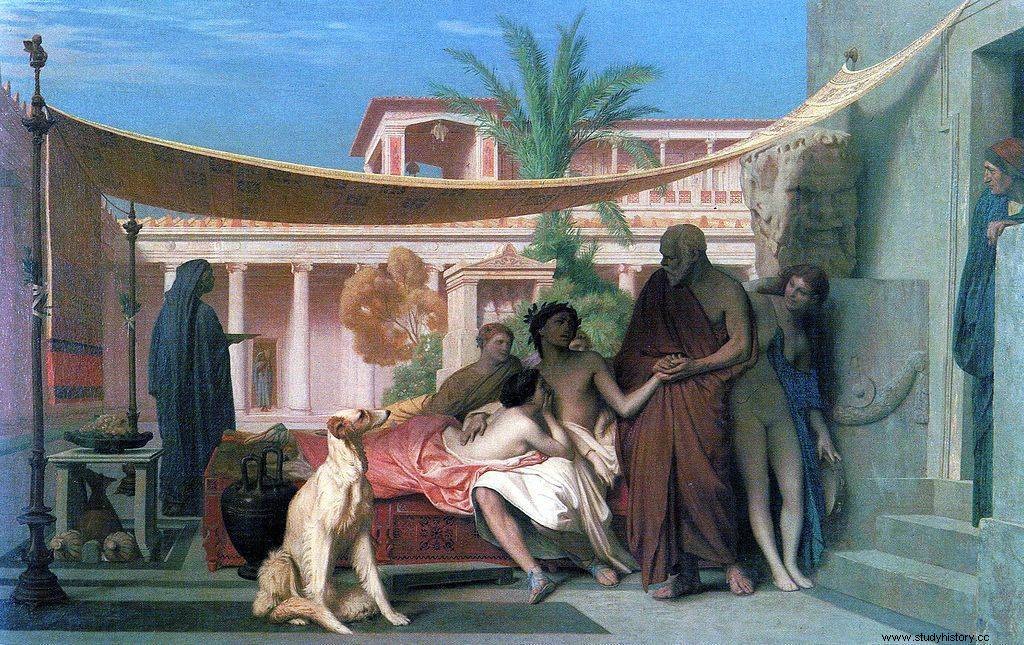

Little is known about Aspasia's life. She was definitely related to Pericles, the Athenian chief who had abandoned his wife for her. Due to her influence on politics, the citizens of Athens accused her of practicing harlotry. Pictured is the painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme "Socrates Seeking Alcybiades in the House of Aspasia" (1861).

Decent women had to know their place. Take, for example, Aspasia, who lives with the Athenian chief Pericles. She came from Miletus, a city known to be extremely debauched from which olisbosses, that is, classic reproductions of the male penis with testicles. She met Pericles when he was already married. However, he got divorced and married the newcomer from Miletus for good.

Before that happened, Aspazja had been his concubine for years, because the wedding was effectively hindered by her foreign roots. This, however, did not arouse controversy among the Athenians. Worse, she was interested in politics and had connections with writers, philosophers and statesmen. It was the protruding of his nose outside the walls of the house and Aspasia's attempts to influence Pericles' decisions that caused the outrage and scandal of the Athenians.

Only a heter, a foreign prostitute, a brothel . Yet even they should not interfere in politics! Therefore, no effort was spared to slander Pericles' partner. Also her name "Aspasia", meaning "Shroud", was used to mock the couple. After all, so many hookers boasting tender lips were called. It was laughed that the Athenian chief was kissing his woman in greeting and goodbye. Poor man, I guess he just dared love her…

Lose to heta

One could say that sexual intercourse was one of the few times when the Greek and Greek worlds came together. However, the truth is that this reunification was still emphasizing the differences.

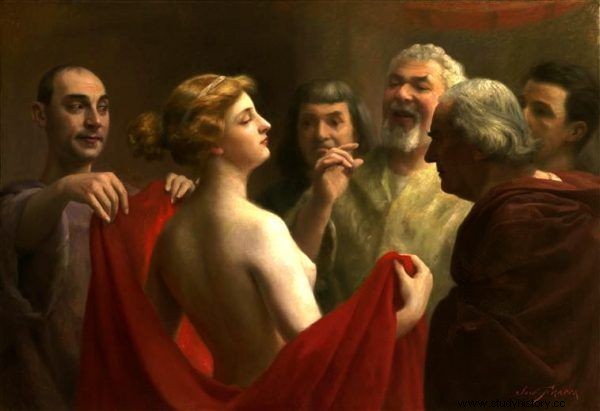

Sex in ancient Athens was the only moment when the male and female worlds came into contact. The wives, however, lost their heads to the famous Greek prostitutes ... In the illustration there is a painting by José Frappa depicting the scene of the judgment over heta.

Why? Firstly, the female body was viewed as deceptive, mysterious and lying - because it was hidden under a layer of costumes, ornaments and cosmetics. Secondly, women were viewed as sexually insatiable . It was believed, for example, that during the intercourse they felt more pleasure than men - and the evidence was the opinion of the mythical seer Tiresias, whom the goddess Hera had turned into a woman for seven years. Thanks to this, he was able to compare the erotic experiences of both sexes (the soothsayer claimed that women experience pleasure nine times greater than men). Thirdly, the woman was assigned a passive, subordinate, and in fact degrading position during the intercourse itself.

Wives - and thus treated by the Athenians as ignorant, inferior versions of a man - were also losing competition with courtesans. Higher class prostitutes, heterosexuals, were especially appreciated. Well-versed in love and unprudent (as you can see on period utensils), they could play instruments, show off their jokes, and if necessary, talk about art and life matters - if only the client had such a need. No wonder the men gave them precious gifts.

From the 4th century BC a controversial thought attributed to the most famous Athenian speaker, Demosthenes, has been preserved. He stated that the Greeks had wives to ensure legal offspring and faithful guardians of the hearth. They also have concubines on a daily basis, and use courtesans for pleasure. Did he mean that Greeks would not enjoy their spouses, or that they would find not only pleasure, but also something more - a family?

This article was written during the author's work on the book "Ages of shamelessness. Sex and erotica in antiquity ”(CiekawostkiHistoryczne.pl 2018).

Even if he wanted to raise his wife's self-esteem, hetery gained fame that has survived to this day. For example, Fryne, the lover of the sculptor Praxiteles, whom she served as a model for the figure of Aphrodite of Knidos. She defended herself against the accusations of impiety by showing the judges her bare breasts. She earned so much money (she was paid at least fifty times the rate of a common prostitute) that she was ready to rebuild the walls around Thebes, destroyed by Alexander of Macedon, provided the Thebans inscribed on them. Centuries later, in modern times, it became the subject of paintings, poems, operas, and was even used to create the literary and serial character of a female detective:Miss Fisher, invented by the Australian Kerry Greenwood.

Evidence of the incredible fascination of ancient hetteras is the fact that some Greeks considered one of the pyramids of Giza to be in honor of the call-girl from the 6th century BC named Rodopis. She once shared a slave fate with Aesop, then she was liberated by her brother Sappho, and finally she charmed Pharaoh, who was to search for her in a lost shoe, like Cinderella.

The position of heterosexual became so significant that Aristotle himself finally stated that their influence should be prevented . How? Taking care of better education of free women - then men would not look for better female companionship in brothels and at symposiums.

Greek women with beards and sticks

Even great philosophers did not agree on how to treat women and their spiritual qualities. Socrates, for example, argued about the unity and identity of virtue in men and women. Aristotle was opposed to it. Not surprisingly, then, from the 4th century B.C.E. until the 2nd century AD in some Greek cities there were services known as gunaikonomoi that is, "overseers of women."

"Aphrodite of Arles", a Roman copy of "Aphrodite of Theses", a sculpture by Praxiteles probably posed by Fryne, considered the most famous hette of ancient Greece.

They were intended to control the conduct of sex more beautifully not only in public places but also in homes. They checked her behavior during religious ceremonies and her clothes - when they left for the city of Athena, they had to cover their head with a veil, a scarf or even the edge of their coat. Today it seems unbelievable:we are not talking about the Taliban state, but about the cradle of our civilization!

On the other hand, there were such sensations as the Hybristika festival held in Argos, during which men and women changed clothes in memory of the impudent ancestors (founders of the family) who once scared the enemy away by donning men's clothes. In the same town on her wedding night, the bride ... put on her beard!

An interesting case was also Gortyna in Crete, where women had more rights than in other Greek city-states. Even marriages between free women and slaves were tolerated there. It was similar with the founders of Lokry, the Greek colony in Italy. Meanwhile, slaves in Athens were treated like animals:for killing their own, no one would bring a citizen to justice, for killing someone else - he would pay a fine. And the Athenians could not only bond with slaves, but even marry with foreigners. For women, this is the most wonderful of Greek polis and it was certainly not the most welcoming place.

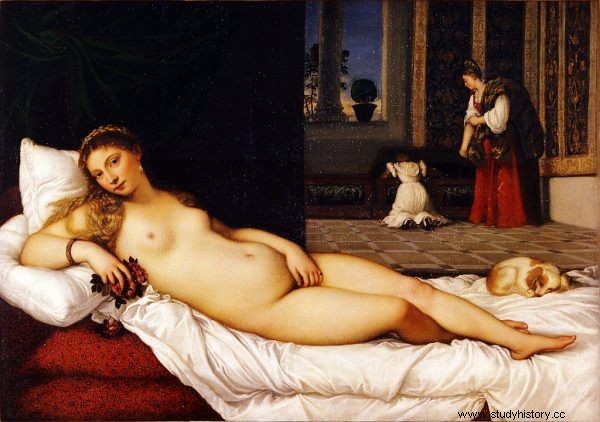

Hybristika was a solemn feast held in the ancient city of Argos in honor of Aphrodite. It was the only such festival during which men and women exchanged clothes. Pictured is Titian's brush painting of "Venus of Urbino" (1534).

The women were constantly monitored, cruelly punished and there was little they could do about it . The sex-strike described by the comedy writer Aristophanes in The Lysistrat so amused the Athenians precisely because it seemed absurd. Like another play by this author - "The Seym of Women". “The exclusion of women from Athenian public life is based on a closed circle of causes at the very heart of culture. Why do women not participate in public life? Because they are not entities that can participate in it. Why are they not such entities? Because this subjectivity is not due to women. The initial premises determine the final thesis "- explained the American prof. James Redfield.

***

The text was created during the author's work on his latest book. " Ages of shame. Sex and erotica in antiquity ” .

Bibliography:

- Aristajnetos, Nanny's Council , in: Ancient Greek Short story , crowd. Romuald Turasiewicz, Ossolineum 2005.

- Jakub Filonik, Athenian trials for impiety up to 399 BCE - analysis attempt , in:Meander, 69/2014.

- Inga Grześczak, Ancient alphabet , Wydawnictwo Akademickie Sedno 2013.

- Richard Hawley, 'Give me a thousand kisses':the kiss, identity, and power in Greek and Roman antiquity , in:Leeds International Classics Studies, No. 6.5 / 2007.

- Herodotus, Happening , crowd. Seweryn Hammer, Reader 2005.

- Mogens Herman Hansen, Athenian Democracy under Demosthenes , crowd. Ryszard Kulesza, DiG 1999.

- Maciej Jorica, Adultery (moicheia) in classical Athenian society and law , in: Contra leges et bonos mores. Moral crimes in ancient Greece and Rome , UMCS Publishing House 2005.

- Stephen G. Miller, Ancient Olympians , crowd. Iwona Żółtowska, State Publishing Institute 2006.

- Emile Mireaux, Everyday Life in Greece in the Homeric Era , crowd. Stanisław Kołodziejczyk, State Publishing Institute 1962.

- Don Nardo, Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece , Greenhaven Press 2007.

- Josiah Ober, Athenian Legacies:Essays on the Politics of Going on Together , Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Pausanias, Wandering around Hellas:In the temple and in the myth , crowd. Janina Niemirska – Pliszczyńska, Ossolineum 2005.

- Pausanias, Walking in Hellas:On the Olympic track and in battle , crowd. Janina Niemirska – Pliszczyńska, Ossolineum 2005.

- Plutarch, Lives of Famous Men , crowd. Mieczysław Brożek, Ossolineum 1976.

- Pseudo-Demosthenes, Against Neajra , in:Iza Bieżuńska-Małowist, Women of antiquity:Talents, ambitions, passions , Polish Scientific Publishers PWN.

- James Redfield, Man and Home Life , in:Jean-Pierre Vernant, The Greek Man , crowd. Paweł Bravo, Łukasz Niesiołowski – Spano, Świat Książki 2000.

- Joyce E. Salisbury, Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World , ABC-CLIO, 2001.

- Lidia Winniczuk, Women of the ancient world. A selection of texts by Greek and Roman authors, PWN 1973.

- Andrzej Wypustek, Family Life of the Ancient Greeks , National Institute for them. Ossoliński 2007.

- Pierre Vidal-Naquet, The Black Hunter. Forms of thought and forms of social life in the Greek world , Prószyński i S-ka 2003.