By 1945, over 14 million people had been forced to work in special camps operating for the benefit of the Third Reich. They were created to make the most of "subhumans" and prisoners of war. As the Nazis themselves admitted, it was about "extermination through work".

The labor camps set up in different places in German-occupied Europe were very different from each other. Some looked like ordinary factories with adjacent barracks for workers, while others - especially those located near concentration camps - resembled the worst hellish visions. Whatever impression they might make from the outside, they all had one thing in common:most inmates were never released again. They either died on the spot or after being sent to a death camp.

The prisoners were faced with hunger, disease, exhaustion, murderous work, as well as sadistic ideas of the guards and paramedical experiments. Each day could be their last - and yet some spent months or even years in the camps. What was their everyday life like?

Day one:accommodation

It was not easy for the camp authorities to provide a roof over the heads of the masses sent to work. Hundreds of thousands were deported. According to Dr. Bogdan Musiał, a historian dealing with the problems of World War II, the Holocaust, communism and National Socialism:

(...) German occupation policy was aimed at (...) the forced recruitment and deportation of men, women and entire families to physical labor in the Reich. According to estimates, a total of 2.82 million people from all Polish territories were transported to this work - which is approx. 15 percent. working age population.

The Germans "recruited" workers, among others, in street round-ups. Photo from Marseille.

12.2 percent were deported from the Wartheland. population. From South-East Prussia, forced laborers were sent to work, especially on peasant farms in East Prussia. However, with the so-called Eastern Upper Silesia and Gdańsk-West Prussia were deported only 3.5 percent. Poles (...). From the General Government to the Reich, the Germans deported about 1.2 million workers who had to perform forced labor in agriculture and industry.

Most often, the question of accommodation was solved simply by ... cramming the inmates as tight as possible. A very effective solution, which at the same time consumed only a small amount of resources, was also the construction of barracks where prisoners gathered during their rest. Such buildings can be seen in Auschwitz, Gusen and Buchenwald. There was no heating inside, so in winter many prisoners simply froze or died of hypothermia.

The capacity of the buildings of the female work center in Ravensbrück was estimated at around 6,000. Meanwhile, there were over 50,000 prisoners! Women had to live in eternal crush, often they slept on the floor, without access to any form of cover or bedding. For five hundred people there were three doorless latrines.

The prisoners of the Mittelbau-Dora complex, who lived underground , had particularly difficult living conditions . They worked in building tunnels, and never went out into the sunlight. This, of course, worsened their health even further. It is estimated that as many as 20,000 people died in this camp. Other centers, faced with overpopulation, quickly supplied the crematoria, and then also gas chambers, where unproductive workers were disposed of.

Day two:order comes first

After arriving at the labor camp, the prisoner read the local regulations. The short codes mainly contained prohibitions and obligations. Rather, the forced laborers might have forgotten about their rights. For example, at the box factory in Aschersleben, where Edith Hahn-Beer was sent, who described her memories in the book "The Nazi's Wife. How a certain Jewish woman survived the Holocaust ”- the rules were very clear.

You could only use the toilets on your floor and wash yourself only at certain times on selected days. No objects could be placed on the tables next to the beds, and the mattresses had to be kept in perfect condition at all times. In order to keep the appearances, the employees were allowed to leave the premises of the plant on Saturdays and Sundays to take a few-hour walk. However, it was forbidden to go out without a special yellow star, pinned to the costume to clearly indicate their Jewish origin . Moreover, strollers were not allowed to buy anything.

In the event of non-compliance with the regulations, financial penalties were imposed on women staying in the "workplace", which were deducted from their salaries. Exactly so - inmates of forced labor received their salaries! But what if they could not issue them in any way, and they were cut at every opportunity. For example, more than half of Edith's first paycheck was taken. How is this justified? Well, the money taken from her was to cover the penalties, the costs of a place to sleep, as well as excess electricity ... used during overtime !

Aschersleben was a very humane place in terms of rules. It even happened that the prisoners experienced sympathy on the part of the guards there. Meanwhile, there were dozens of camps outside Germany where workers were treated no better than the replaceable part of the pickaxe. In the basement of the Reise and Mittelbau-Dora complexes, as well as in the Gusen quarries, the guard had total power over the prisoner.

Day three:crime and punishment

Forced laborers, even for minor offenses, could be locked up in solitary confinement or flogged. For example, this was the case with female prisoners living in the Ravensbrück camp every day. Unfortunately, when the wardens of the women's facility began to get bored, they invented more "fun" methods of administering justice. For example, trained dogs were set down on disobedient women - such a punishment was often fatal.

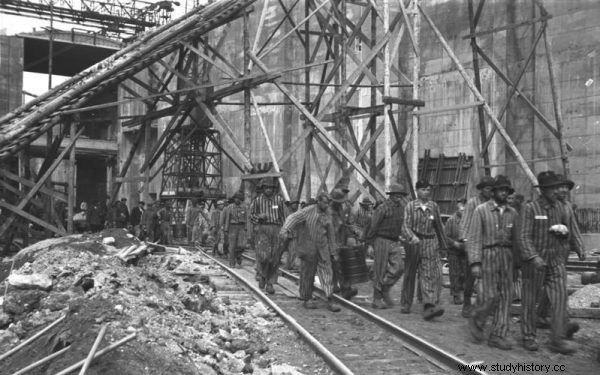

A huge part of the workforce was made up of concentration camp prisoners, used, inter alia, by industry. In the photo there are prisoners from Bremen.

Ravensbrück went down in history in black letters not only because of the sadistic tendencies of women - guardians. The prisoners were also regularly subjected to medical experiments there. They tested, among other things, the antibacterial effect of sulfonamides during the healing of difficult wounds. "Patients" had to be wounded to simulate a real accident - the doctors wounded women in prison with pieces of dirty glass and wood. After the onset of gangrene symptoms, drugs were administered, most often to no avail.

The camp "doctors" also searched for methods of bone transplantation and nerve regeneration, so they amputated the limbs of prisoners "in the name of science". A group of women deported from Romania voluntarily agreed to undergo sterilization in return for freedom . The surgery was done, but the Romanians remained behind bars.

Day four:Arbeit macht frei

Of course, the main part of the inmates' day was work. Regardless of its type, production or output standards were strict and almost impossible to meet . Moreover, the prisoners spent several hours a day on arduous and devastating classes. Ravensbrück detained in the camp woke up at 4 am and first replaced machines in road construction, and in the afternoon they sewed uniforms for German soldiers.

Meanwhile, in Aschersleben, where Hahn-Beer was staying, cardboard packaging for food was produced, in which German citizens would later buy rice or coffee. In the book "The Nazi's Wife. How a certain Jewish woman survived the Holocaust ", the woman recalls how, after her arrival at the camp, the daily standard for the production of cardboard packaging was established:

I was sweating, my heart was pounding, my fingertips were burning from pushing the cardboard in and out. Felgentreu counted the number of boxes I cut, multiplied by six and thus calculated the hourly quota. Then he multiplied it by eight and gave me the daily quota:twenty thousand boxes .

The inscription "Arbeit macht frei" on the gates of many camps sounded in the ears of the workers forced to work like a cruel mockery.

Later, this standard was increased because slave labor was not enough to meet the needs of the German economy. Workers sat at the cutters ten or more hours a day. With 3800 cut boxes per hour, which in a simple calculation is about 38,000 a day, even a skillful worker could not stand it. Edith wrote:

The cardboard has rubbed the skin on my fingers into a bloody mush. I would have liked to use gloves, but it was not possible to operate the machine efficiently then - the gloves slowed down the movements and increased the likelihood of my fingers being severed . So I was just bleeding .

The girl was lucky anyway - in places such as Gusen or Mittelbau-Dora, employees often died while working. The whole days spent hammering rocks or digging tunnels turned out to be so exhausting that it didn't take disease or punishment to kill them. Similar conditions prevailed in the mines in the Riese complex, where the workers from the Fürstenstein camp received only prison clothes and starvation food for their slave labor. This is how a resident of Walim recalls this period:

We were crossing the footbridge to the street and in the ditches below we saw men, very young among them, almost children. Skinny to the bone, without sufficient clothing. In autumn and winter they wrapped themselves in cement bags .

Hieronim Grębowicz, who worked on the construction of the Riese complex, recalled years later:“There was constant work there, they rode twelve hours a day. When [the employee] died, it was a brigade of four boys and over the hill. ”

The article was inspired by the book by Edith Hahn-Beer "The Nazi's Wife. How a certain Jewish woman survived the Holocaust ” (Napoleon V 2019).

The sarcastic inscriptions "Arbeit macht frei" above the gates of many camps testify to the inhuman attitude of the Nazis towards forced laborers to this day. Liberation - Yes, but only through death. And in the meantime companies such as Linz, Bayer, Sauerwerks and Junkers could enjoy free labor .

Day five - meal and sleep

Eating and resting, two elements of life that would seem most important to the well-being of every human being, were reduced to a minimum in labor camps. Edith Hahn-Beer reports that the workers at the dinner packaging factory received poor quality coffee, mostly made from acorns, and two pieces of bread. For dinner, a soup of water, potatoes, celery and cabbage was prepared - a not very nutritious and calorie-rich meal for a hardworking person.

It happened that the workers received parcels from someone outside the camp. In such a package - if he managed to get through post office checks at all - often contained, for example, bread. After many days of travel, the loaf was dry and rock-hard, but was eaten straight away. Hahn-Beer reports that a great way to restore even a little softness was to wrap it with wet cloths before consumption.

During the “free” time that prisoners of some camps could spend for a walk, they liked to simply rest. Every moment of sleep was worth its weight in gold, every calorie saved could make up for life or garbage.

Day Six - Little Pleasures

Prisoners were often sent to labor camps of their own free will. Nazi propaganda attracted young, healthy people to work abroad. Inmates were often promised that in return for their work the safety of their families was guaranteed.

To work on a mining project code-named Riese, the Germans employed thousands of forced laborers.

Next to them were forced deportees "dangerous" to the Nazis, ie intellectuals, artists and representatives of the opposition. They tried to maintain the culture and memory of normal life by secretly singing songs and storing books. According to the accounts of some prisoners, the moments when they managed to sabotage some element of the Nazi death machine brought the most happiness and satisfaction. For example, part of a ballistic missile control system.

The economy of Germany during World War II was in a tragic condition and had it not been for the work of millions of slaves, the Third Reich would have collapsed much faster. It was only by enslaving others that the Nazis were able to maintain their rule for so long…

Bibliography:

- Czesław Madajczyk, Politics of the Third Reich in occupied Poland , PWN 1970.

- Feliks Załachowski, Gusen - death camp, Association of Former Political Prisoners 1946.

- Extermination of Polish Jews during World War II, comp. Adam Puławski, Agnieszka Jaczyńska, Dariusz Libionka, Institute of National Remembrance 2007.

- Zbigniew Dawidowicz, Riese - the Nazi underground of death , Technol Publishing House 2007.

- Edith Hahn-Beer, The Nazi's Wife. How a certain Jewish woman survived the Holocaust, Napoleon V 2019 publishing house.