They were said to be drunkards, illiterate and syphilitic. Their activity was surrounded by almost universal contempt. They were paid poorly and mistreated - and yet there were still new takers. And they built the power of Great Britain.

“Rule Britanio, Rule over the waves Great Britain” - the words of Britain's unofficial anthem best describe what has happened in the seas and oceans since the 18th century. The British fleet unquestionably placed other nations in the corners (or rather on the edges), filling the nation with pride. And yet the same people who dwelt on the maritime power of their country, complained in one breath at… those without whom this success would not have been possible. For the seamen.

In 1869, British diplomats in port cities around the world, commissioned by the Chamber of Commerce, prepared a report on the crews of native ships. The most frequently used term was not so much a sea wolf as "drunkard", followed by "syphilitic", "illiterate", "dishonest" and "insubordinate". To sum up, the British seaman was commonly perceived as ... "an ordinary chilling and working animal" . The opinion of the diplomats was confirmed by the English writer Daniel Defoe, noting that “sailors are cruel in their every move. They curse cruelly, drink cruelly, waste money cruelly. ”

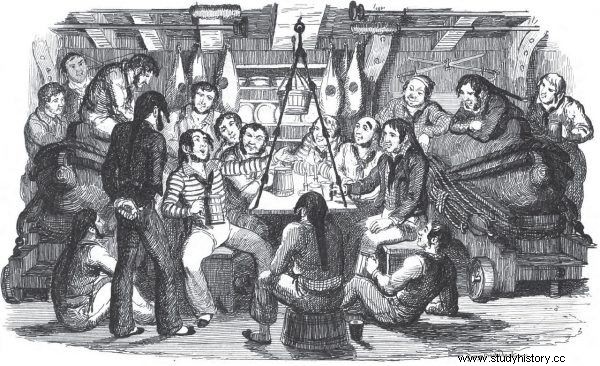

A sea of beer for everyone

Admittedly, the critics were at least partially right. But when it comes to drinking, the policy of the Royal Navy was not without blame. The provisions on provisions from around 1740 assumed that each seaman should receive up to 7 gallons of beer per week, or almost 32 liters. So he drank up to 4.5 liters of the golden drink a day!

Beer is "the binder that binds the body and soul of seafarers together," admitted at the beginning of the 18th century the writer hidden under the pseudonym Barnaby Slush. Interestingly, from the mid-17th century (after the takeover from the Spaniards of Jamaica), the allocation of beer was sometimes replaced with rum, and later with grog.

The sailors had at their disposal… even 4.5 liters of beer a day!

The latter invention, a mixture of water and rum with the addition of lemon juice, in addition to improving the mood of sailors thanks to vitamin C, contributed to the fight against scurvy. After the Napoleonic Wars, the sailors only received grog. This practice continued on British Navy ships until ... 1970!

The amount of drinks consumed does not mean, however, that the sailors went around constantly drunk. The beer that was taken to the ships was alcoholic 1-3 percent. So it was much weaker than it is today. Why was alcohol taken on board at all? Well, the water just broke during long journeys. Even today, a mineral drink after a few days gives off an unbearable smell. The golden barley drink, meanwhile, also provided calories and ... vitamins, which was extremely important with a fairly uniform menu.

Shark-eaten porridge

“The English, and especially sailors, love their bellies above all else,” wrote the memoirist Samuel Pepys, once responsible for the provisioning of the fleet, in the mid-seventeenth century. Foodies, however, had nothing to look for in the Royal Navy. The staple food consisted of rusks, porridge and salted meat - beef and pork. The latter was soaked in water for hours to make it edible again.

For obvious reasons, there was a shortage of fresh fruit and vegetables. People tried to break the monotony of meals by getting fresh meat in ports and fishing. However, not all sailors agreed to culinary novelties. Some refused to eat sharks . As they claimed, these predators eat people, which means that by eating them they would become… cannibals.

Food rules have remained virtually unchanged for centuries. In 1878, the writer Konrad Korzeniowski struggled with the monotony of caboose food. Before he gained fame and critical acclaim, he served as a sailor on the Duke of Sutherland. His standard day is described in the book "Joseph Conrad and the birth of a global world" Maya Jasanoff:

He swung his legs over the edge of the bunk and, with his heels sore from being bitten by rats at night, climbed the drip. A quick rinse and wipe with a rag, then into the galley to scoop a few dips of gray porridge from the onion. He leaned against the sail to eat and swallow coffee from a tin mug.

Despite these inconveniences, it is worth emphasizing that if the seafarers found an honest skipper who did not steal during the provisions and the food did not spoil - which was easy in damp and musty holds - consumed up to 5,000 kcal per day . This is much more than today's standard for a physically working man, which is up to 4,500 calories.

Konrad Korzeniowski has used many ships. He was, among other things, the captain of the "Otago" pictured.

However, the sailors worked for 12 hours. No wonder they were able to rebel over a shortage of food. In the years 1740–1820 there were as many as 62 revolts. 13 percent of them exploded due to poor provisioning. The number one dissatisfaction was due to being treated too roughly.

Cat to whip

The officers had a wide arsenal of corporal punishment. Flogging was one of the most popular. It was aimed at the formidable "nine-tailed cat" - a whip with nine ends that literally massacred the poor man's back. From 1750, the maximum penalty was 12 strokes, but as the ship's doctor of the time claimed, it was enough to make the back "swollen like a pillow in black and navy blue."

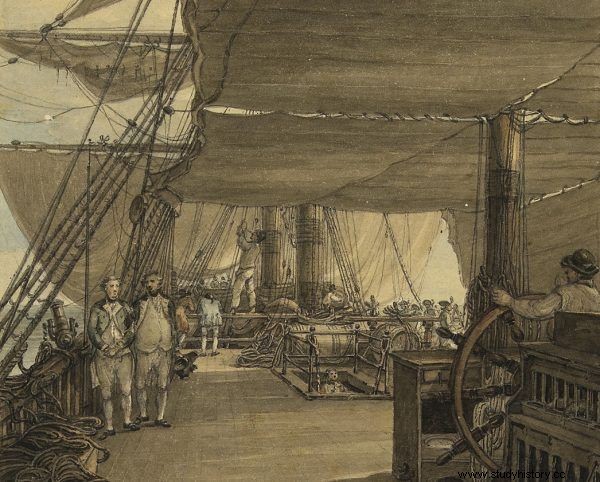

A public performance was made of the administration of punishment to maximize its deterrent and educational effect. The entire crew was gathered on board - officers and sailors separately. The victim was stripped from the waist up and tied to a mast or rigging. The thieves were chased away by a line of sailors waiting for them with whips or pieces of rope. The lazy or too slow-working could suddenly receive a single "encouraging" rope hit - the so-called starter .

The worst offenses were falling asleep while on duty, insubordination and… lack of hygiene. The Royal Navy was obsessed with cleanliness. In this way, attempts were made to combat the scourge of diseases spreading on board, such as dysentery and typhus. Only a few seamen, including those working on sails, were exempted from the obligation to constantly scrub the deck. Those who did not take care of the rest on board were also constantly tracked.

Cleanliness was almost obsessed on board ships of the Royal Navy.

It didn't do much. As he writes in the book "Joseph Conrad and the birth of a global world" Maya Jasanoff, also Korzeniowski "got to know a peculiar stench of subsoil, sticky and musty, which is best fought by smoking a pipe or completely stuffy nose". This was due not only to the diagonal emptying of the bladder, but also to infrequent body washing and insufficient ventilation.

Prison with the possibility of drowning

The strict discipline and poor living conditions were not compensated by the salary. As Adam Smith wrote in 1776 in The Wealth of Nations, the average seaman of a merchant navy leaving London could count on a salary of 21-27 shillings a month. At the same time, the laborer was earning 40–45 shillings. In other ports, rates for sea wolves were even lower.

Royal Navy sailors could count on even lower salaries, which led to the rebellion in 1797. No wonder Dr. Samuel Johnson, an English writer and lexicographer, noted that "no man inventive enough to keep himself in prison will become a sailor; for life on board is life in a prison, with the added possibility of drowning " .

So where did the sailors come from? Some of them chose this profession, continuing the family tradition. Others got carried away by the lust for adventure. The sea offered a journey into unknown, exotic lands, male friendship, and also ... enabled social advancement.

The sea offered a journey into unknown, exotic lands, male friendship, and also ... enabled social advancement.

Suffice it to mention that James Cook himself was born the son of a farmer. He began his career at sea as an ordinary seaman. He ended up as a great explorer and captain in the service of His Majesty. Konrad Korzeniowski, on the other hand, found employment on the ship with almost no knowledge of English. He also got the captain's license. Stories like this were not uncommon.

The Royal Navy had one more way to replenish its crews. In 1793, the so-called Impress Service, i.e. the recruitment service, was formalized. The problem is that recruiters did not so much persuade the young men to join the navy, but kidnapped them from the streets . In this way, they wanted to replenish the ranks of the fleet, which during the war needed up to 60,000 additional hands to work. Men who already had experience in the civilian fleet were most in demand.

There were even some recruiters raiding merchant ships and kidnapping crew members! This draconian system was not abolished until 1833. Then only those who wanted to remain at sea.

Bibliography:

- Maya Jasanoff, Joseph Conrad and the birth of a global world , 2018 Poznań Publishing House.

- E. Koczorowski, Mast and sails people , National Publishing Agency 1986.

- Andrew Lambert, War at sea in the age of sail , 1650–1850, Harper 2005.

- B. Lavery, Shipboard life and organization , Navy Records Society Publications 1998.

Buy the book at a discount on empik.com