Caesarean sections were performed in antiquity, but they became safe only recently ... In which one extremely durable inhabitant of Holstein helped a lot.

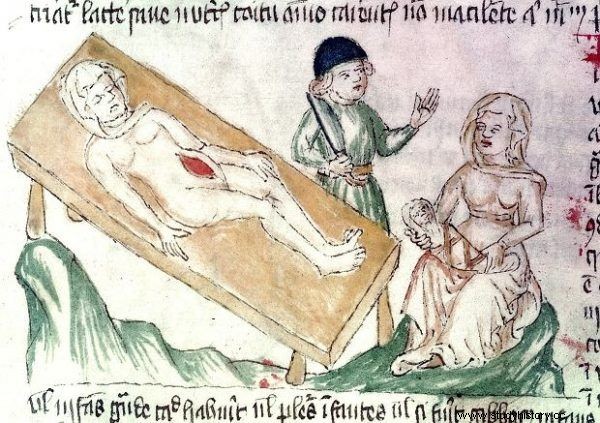

Caesarean sections were performed long before Christ was born in many ancient civilizations. Be it for religious and cultural reasons, or by trying to save the mother's child who is dying. However, for many years no one thought that a pregnant woman would have a chance of surviving the procedure (although such cases could happen sporadically).

The medical world learned that a cesarean section could only be carried out with the hope of a successful end for both the baby and the mother in the 19th century. How did it come about? One by one…

A cut has more than one name

At the outset, it is appropriate to clarify the problematic issue of the name. People speculate that it comes from the way Julius Caesar was born. This legend was upheld by Pliny the Elder in his Historia Naturalis however, according to scientists, it seems unlikely. Caesar's mother survived the childbirth, which was then almost impossible.

A better explanation of the origin of the word "imperial" is the altered form of the Latin word caedere , which simply means cutting. Meanwhile, the name Caesar (Caesar) probably comes from something else entirely:the words cesaries , meaning long hair. One of Caesar's ancestors may have worn this hairstyle.

For centuries, it was considered impossible for a woman to survive a caesarean section

Another theory explaining the origin of the name caesarean section concerns a set of Roman laws that specify that the child of a dying or still pregnant woman should be removed from her womb before burial. These recipes were called Lex Caesarea.

Today we do not know the true source of the name of the procedure, but it is well known that until 1598 it was called "imperial surgery". French surgeon Jacques Guillimeau in his book for midwives called the procedure a Caesarean section for the first time.

Guillimeau's book was 17 years ahead of the publication of a treatise by another surgeon François Rousset (criticized until today for his unscientific approach to medicine), in which he proclaimed the possibility of a wider use of the procedure on living women who, for various reasons, cannot give birth to a natural child. He called the incision "enfantement césarien", or "caesarean birth" and argued that it could be a way to save not only the baby but also the mother.

A very old procedure

The ancestors of today's Hindus claimed thousands of years ago that their god Indra refused to be born "by the dirty road" through the vagina. So he was cut from the side of his divine mother. Also for Buddhists, the birth canal was unclean. Therefore their Buddha came out immaculate from the right side of the mother. What was right for the Buddhists was also right for the ancient Greeks and Romans.

- writes Jurgen Thornwald in "Gynecologists".

The same author also mentions the legend of Gebhard I, Bishop of Constance from the 10th century, who was supposed to be removed from his mother's womb and matured in the belly of a pig ...

The doctrine of the church also clearly stated that all unborn children are condemned to purgatory, so they (in the event of their mother's premature death) had to be taken outside and baptized.

The Caesarean section has been known since antiquity, but almost always ended with the mother's death

Whatever the reasons for bringing the children into the world, there are semi-mythical examples of the procedure being used in ancient China (the Yellow Emperor's six sons were to be born this way), India (Emperor Bindusaya was to be taken by the scholar Chankaya after that how his mother accidentally ingested the poison), as well as Ireland (the allegedly legendary Furbaide Ferbend was born through Caesarean section) or Jewish culture (the yotzei dofen procedure is mentioned in the Talmud. reportedly experienced by many women).

As you can see, the idea has existed in the minds of scientists for a very long time.

Pig castration and 15% chance

French surgeon Rousset predicted that caesarean section could be performed safely and for the benefit of the baby and mother, but until the 19th century, postoperative female mortality was extremely high. Surgeons resorted to it as a last resort, knowing the dire consequences:even if the mother did not die on the operating table, she usually passed away in agony over the following days. The reason was usually contamination, which was inevitable in the sanitary conditions of the time.

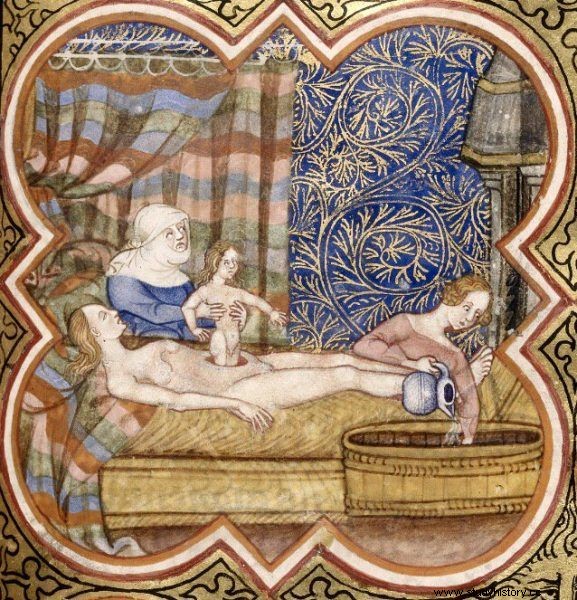

The first successful and reasonably well documented cut in which both mother and child survived, however, took place as early as the 16th century in Switzerland.

Interestingly, it was not even carried out by a doctor, but ... a pig castrator! A man named Jakob Nufer operated on his own wife, who survived and in the following years she repeatedly had successive pregnancies. A pig castrator made a risky decision after his wife was unable to give birth for several days.

The first Caesarean section in which the mother survived was performed by a ... pig castrator!

When the "thirteen midwives" tried in vain to deliver Eva, Jacob offered to open up his wife's body. Only two midwives had the courage to accompany the birthing woman, while Jacob, after praying, made the cut. Eva remained alive, and her daughter lived to be seventy-eight years old. However, since Mrs Nufer later gave birth to four more children by force of nature, medical historians speculate that Jacob did not cut his wife's uterus, but freed her from an abdominal pregnancy - a child who, through the whim of an egg and sperm, was conceived in the abdomen instead of the uterus

- we read in Jurgen Thornwald's "Gynecologists".

After cutting her belly open and taking the baby out, he sewed her up in the same way as the animals he handled everyday. Unfortunately, this case has not been completely and reliably documented and cannot be treated indiscriminately as a historical fact.

Well-documented caesarean sections in which mother and child survived were not performed until the 19th century, in both the UK and the US, when doctors performed surgery to save the life of the child and, with a low probability, of the mother.

According to data collected for 1865, survival of women after surgery was about 15% . This worrying value only rose later with the introduction of hygiene, antiseptics and antibiotics in hospitals.

However, before doctors began to approach caesarean section more boldly, they needed hard evidence that the procedure could be performed without permanent harm to the mother's health ... It just so happened forty years before the horrible statistics were compiled!

Fierce Anna

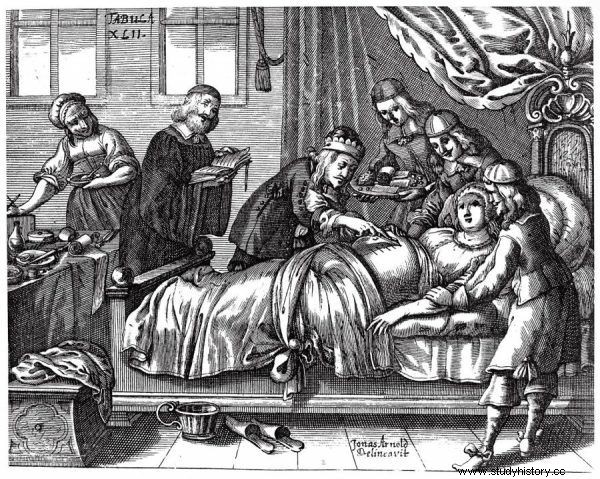

A real breakthrough in the approach to Caesarean section was the story of Anna Margaretha, who survived the procedure ... four times, in the 1830s!

Resident of the Holstein village of St. Margarethen, Wenzel's wife, first became pregnant in 1825. On June 16 of the following year, labor pains began, but despite the water's departure, the baby was not born. Dr. Siedel was summoned, who stated that the child's head was stuck and would not move any further. Then, at the urging of Wenzel, the surgeon Zwancek was called, who performed a caesarean section, having previously tied the woman to a table in the kitchen.

The child was born still, but Anna survived the infection and ... soon became pregnant for a second time, despite Zwancek's strict orders. When the time came for delivery, the surgeon referred the woman to the Kiel maternity clinic, where he was seeing Dr. Wiedemann. Although no one had ever performed a similar procedure twice on one patient before, the doctor cut open Anna's abdomen and brought the girl alive, and then sewed up the wound in five minutes.

Caesarean section has become safer for the mother, incl. thanks to the discovery of asepsis and antisepsis

Unfortunately, the child died shortly thereafter from an unexplained disease (scholars speculate that it was due to a respiratory tract infection; babies delivered by caesarean section have immunosuppression which was not known at the time).

Anna came to the Wiedemann clinic for the second time at the beginning of March 1832. She was pregnant again. This time the old doctor did not undertake the procedure, sending the patient to his ward, Gustav Adolf Michaelis. On March 28, he performed an operation that lasted forty minutes, after which the haemorrhage was barely stopped and the wound was sutured. This time, however, after two months, Anna returned home with a living and healthy child - Cäsar-Karl, who died of scarlet fever only after eight months. Michaeils published an article about Anna that traveled all over Europe and caused quite a stir in the medical world.

Anna Margaretha returned to the clinic in 1836 for the last time to undergo a caesarean section. This time, the wound that was opened many times did not want to close, remaining open for a month . Anna was already famous, the godfather of a girl named Friederike Caroline Luise Cäsarine was the King of Denmark, Frederik himself.

Incredible as it seems, the mother survived. She did not become pregnant again, and she died only in 1864. Her daughter Friederike Caroline Luise Cäsarine lived to old age.

Thanks to the incredible story of Anna, Caesarean section appeared in the medical community in a completely new light. In 1847, it was discovered that maternal fever was passed on to women by lack of hygiene in hospitals, as reported by Dr. Schwarz from Vienna on December 21st. Doctors working in maternity wards gradually began to wash their hands with chlorinated water, greatly reducing the risk of infection. At the end of the road to safer cesarean sections (and generally safer procedures in hospitals) the goal finally emerged.

Source and inspiration:

- Thornwald, J., Gynecologists . Marginesy Publishing House, Warsaw, 2016.