"We strongly ban these vanity fairs - tournaments in which knights meet and thoughtlessly engage in showing off their agility and strength, which often results in death (...). There is a threat to the soul. If anyone is killed in their time, ... he cannot be buried by a priest in a consecrated ground, ”proclaimed in 1130 the conciliar canon of the combined church councils of Clermont and Reims. Yes, the clergy were against the tournament skirmishes for which they actually ... allowed themselves.

"Among the many soldiers who have been in military arenas for centuries - from Greek hoplites, Roman legionnaires and Ottoman Janissaries to members of the elite formations of modern armed forces - no one has had such a great influence as knights on history ..." - writes in his book The life of a medieval knight Frances Gies.

Although we could probably add other examples of significant military formations in history (such as the hussars adored by Poles), indeed knights dominated for almost a thousand years both on the battlefields, as well as in politics and culture . It is this last area of social life that is closely related to the knightly tournament.

Duels in competitions became an indispensable element of knightly life, because having a fighting horse, heavy equipment and your own post office was not enough anymore. A real knight was not only one who distinguished himself in battles, was gallant towards women, understanding towards a defeated opponent or generous towards the needy. In order to achieve the ideal, it was also necessary to demonstrate in mock fights.

Cavalry performances

The beginnings of the tournaments are lost in the darkness of history, which makes them difficult to pin down. Probably the genesis of chivalry games has its origins in all kinds of ancient dexterity shows and military exercises. Already in ancient Rome, there were some kind of mock fights. These were, among others, cavalry performances described by the Greek historian Arrian.

This custom was adopted only during the times of the empire, when the need to maintain more and more driving forces forced the rulers to take care of this previously neglected type of weapon. These performances, known as hippika gymnasia, perhaps initially they were associated with religious and state holidays. Ultimately, however, were to demonstrate the strength, agility and splendor of the imperial army . According to the historian, there were two units in different colors of tunics, shields and horse blankets. It was determined in advance which group was to defend and which to attack. Throws of javelins were counted, as well as effective shields.

The need to maintain increasing driving forces forced the rulers to take care of this previously neglected type of weapon

The undoubted spectacularity of these displays was influenced by the richly decorated and gilded armaments of the fighters and their mounts. All these procedures must have cost a fortune, but in order to increase the prestige and impress both strangers and people, expenses were not taken into account. Just like the medieval times of skirmishes.

Group and individual lessons

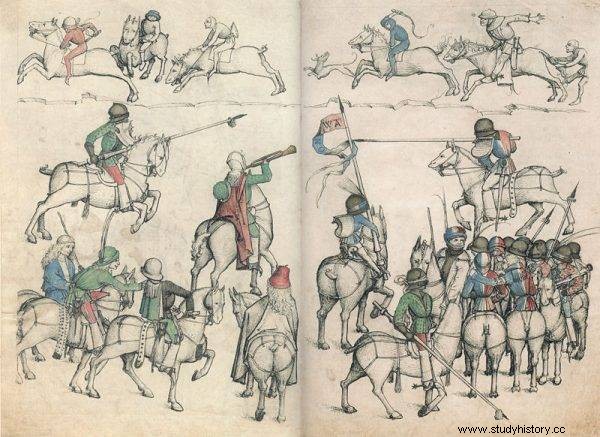

The custom of simulated fights adopted on medieval soil has become a substitute for real struggles. It was a training in the difficult art of using weapons. Stumbling in the competition, initially over an area of even many square kilometers, helped to gain skill in unloading the opponent from the saddle.

At the same time, the first tournaments, as Frances Gies emphasizes, “ were not about individual horse clashes against lances. Instead, there was a collective »brawl« ( melée ), in which two sides fought a mock battle ”. Teams tried to break the opponent's ranks with the strength and mass of their own ranks. Compact formations, however, left enough space for bravery and combat skills to be demonstrated.

Initially, there were no formal rules for playing tournaments, which made these simulations even more like a real battle. There was no specification of illegal strikes or tactical plays. In The Life of a Medieval Knight we read that "the tournament was to be an imitation of a real war, so it was not considered" unsportsmanlike "to attack one knight by several others or to take a wounded prisoner.

The text was created, among others based on the book by Frances Gies "Życie medieval knight", which has just been released by the Znak Horyzont publishing house.

The lack of formal rules and the ways of their possible respect for them made the general goal of capturing and extorting a ransom on the defeated party, rather than extermination, also difficult to meet. In this situation it was often the case that a mock battle was the last for some daredevils . Apparently, during one of such simulations, 200 knights gave up their spirits from crush, heat and dust. There is also an example of a tournament organized in 1243 near the city of Neuss on the Rhine, where the number of deaths amounted to 367. And according to Frances Gies, it even happened that these tournament "acts of violence often turned into riots and even armed rebels."

What essentially distinguished a real battle from the sham one was the designation of a kind of refuge where the knight could rest, replace his mount and replace a worn or lost weapon. It was the only license to support the sporting nature of the competition.

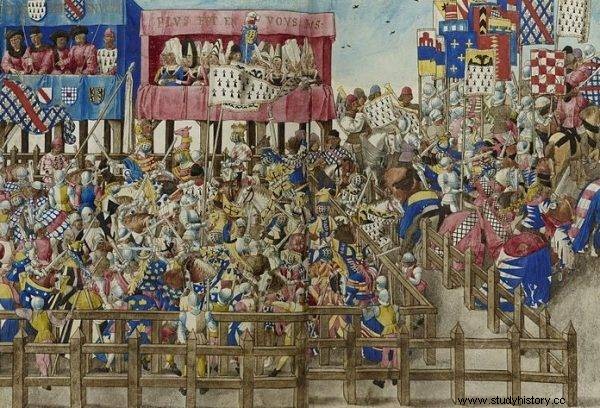

Initially, the motive for participation in the tournaments was primarily the desire and need for knights to improve their combat efficiency. However, the vision of gaining fame soon emerged, not to mention material profits. Gaining the opinion of a brave and trained knight became easier over time, as during the 13th century tournaments moved from open, undefined spaces to city walls, streets and court yards. There, the contestants could and were closely watched by the inhabitants, who became the first oracles of the fighters' successes or failures.

As a result, the very nature of the skirmishes has changed - a group fight has been replaced by an individual one. In this way, a spectacle began to be produced, the inseparable element of which was precisely the viewers, and among them women appeared in a special place.

Women's skirmishes

Ladies not only passively watched the actions of the knights. Frances Gies in The Life of a Medieval Knight notes that with time women "participated in these performances, dressed in the colors of their favorites, stimulated the fighters with their flirtatious behavior".

Also the awards, which began to be awarded more and more often to the winners, were handed out by the ladies of the court. In Germany, this custom has been formalized in some way in the form of the so-called frauendanku - that is, accepting the prize from the hands of the lady. It also happened that noblewomen entered sports matches themselves . Here in 1438 in Ferrara, after the end of knightly duels, the ladies competed in tournament matches, fighting for beautiful and elegant clothes. And after a few days of struggle at the castle in Grodziec, the ladies present there played a shooting tournament.

Ladies not only passively watched the actions of the knights

It was the presence of women at tournaments and showing off in front of them - along with growing luxury, earning money, wasting health and life for vain glory - that made the Church quite unfavorable towards these chivalrous activities almost from the very beginning of the tournament's institution. And it didn't end with the negative attitude.

In competition with the Church

The negative attitude of the church authorities to the tournaments may come as a surprise. After all, they were part of the chivalrous prestige which, according to Frances Gies:

was mainly a result of the Church's policy of Christianizing the knighthood by sanctifying the knighthood ceremony and propagating the pattern behavior called chivalry - a pattern that is probably more often broken than obeyed, but one that undoubtedly influenced the thoughts and actions of the next generations .

Owning a horse and combat gear was expensive, and thus made the owner feel proud of his knightly profession and superiority over other states. From here, it is only a step to scandalous behavior, full of violence in the sense of absolute impunity. This situation required a strong response. "Efforts by the Church to first tame and then subdue the early knight - simpleton and brute - led to awakening in him a sense of belonging to the "order", an elite cadre, whose duties and rules were determined by the church authorities ... "- we read in Życie a medieval knight .

This, however, meant that the knights, henceforth having a church sanction for their actions, most often saw nothing wrong in tournaments, which were supposed to perfect the craft of miles Christi .

"A knight practicing his soldier craft justified only fighting against Christ's enemies"

Therefore, the Church competed with its knights because, after all, quoting Frances Gies - "a knight practicing his soldier's craft, it only justified the fight against Christ's enemies." Church authorities went so far as to issue bans on the organization of tournaments. The chivalrous pursuits were accused of being a dangerous occupation, unnecessarily squandering property, and of becoming a demonstration of vanity and pride.

Spreading debauchery was also accused as the presence of women created an atmosphere of excitement and excitement . This accusation even proved correct with the growing popularity of the custom of knights wearing the colors of their chosen ones. Following another great historian, Johan Huizinga, it can be boldly repeated that "wearing a veil or a scrap of a beloved woman's robe, objects that carried the scent of her hair or body, reveals the most direct erotic element of knightly tournaments." It happened that mighty ladies, remembered, handed out fragments of their wardrobe, remaining almost naked at the end of the tournament. And from here it is close to infidelity - another church argument against the chivalrous games.

A particularly severe anti-tournament campaign took place during the Crusades. It was justified by the unnecessary distraction of knights from their primary duty, which was the fight for the liberation of the Holy Land. In the years 1130–1314, the Church issued a number of general prohibitions regarding the organization of tournaments. Among them was the aforementioned Conciliar canon of Clermont and Reims forbidding the holding of "vanity fairs" under penalty of not being buried in blessed ground.

The church authorities also pointed out that during the knightly games the binding rules of the fight were violated many times. Opponents often mocked one another in front of the public, which, according to theologians, offended the dignity of Christ's soldier.

Slaughterhouse hammer

One of the staunch opponents of organizing tournaments was the Bishop of Acre Jacques de Vitry. He pointed to this the seven deadly sins committed by the fighters . The first was pride, when players sought worldly glory and fame in tournaments. The second was envy, because everyone looked jealously at the successes of another nobleman and wanted to be better than him. The next hatred, because in order to win the knights were ready to kill their opponents. Laziness or sadness engulfed all those who failed in the fight. Greed, on the other hand, made the victors take away the defeated armor and horses.

Just like described in The Life of a Medieval Knight professional tournament participant Wilhelm Marshal, who "threw the first adversary from the saddle, seized his horse and forced a ransom promise, and then took two more prisoners, taking their horses and equipment".

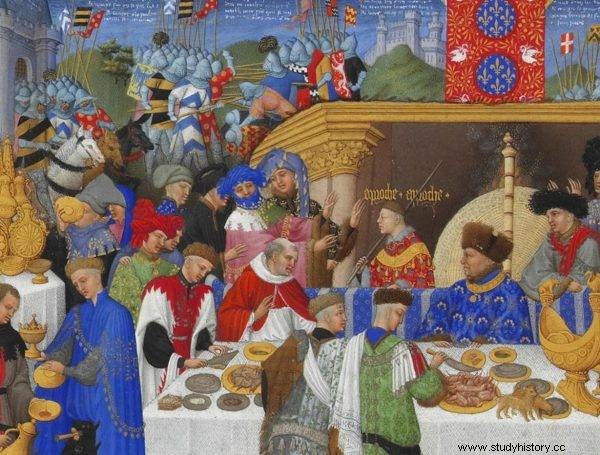

Coming back to the sinful list of the bishop of Acre, he condemned the feasts organized after the competition, which made it possible to commit the sin of gluttony. At the end, of course, he mentioned ... lasciviousness, because the fighters "wanted to please the playful women, wearing their colors in the tournaments".

He condemned the post-competition feasts that gave the possibility of committing the sin of gluttony.

Church authorities also emphasized the uselessness of the tournaments, as participation in them did not increase the efficiency or effectiveness of the fighters. The frequent habit of settling personal scores in the matches was also disdained.

When the prohibitions did not help, the Church resorted to a centuries-old method of appealing to the imaginations of people of the Middle Ages susceptible to suggestion - tournament participants were presented with visions of terrible torments that would befall the fallen in the competition. For these unfortunates were already spiked armor inside, flames, white-hot iron beds and hugs of disgusting creatures , such as a toad. It was emphasized that those who die in a knightly tournament would surely end up in Hell, unless they repented before dying.

However, all the efforts and calls to refrain from organizing skirmishes and taking part in tournaments came to nothing. The popularity of chivalrous entertainment was so great that it could not be effectively limited. In the end, the clerical authorities had to give up. Finally, in 1314, Pope Clement V lifted the restrictions and since then the Church no longer issued official prohibitions of this type. However, there were still such cases of a regional nature. An example is the synod of the diocese of Płock from the end of the 14th century, which also made a rather blunt statement about the games of the knights, comparing them to ... a butcher's slaughterhouse.

Knightly Indian Summer

With the abandonment of church restrictions, there was an evolution of knightly fights into more staged shows. The desire to improve the skills needed in a real fight began to recede into the background. Of course participating in tournaments still improved these skills, but they were no longer an end in themselves.

One of the reasons for this was the changes taking place on the battlefields during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in the Western European theater of war, where increasingly began to use infantry . So far, during the peace period, tournaments have been practically the only opportunity for military exercises, regardless of whether they were collective or individual skirmishes. The acquired skills were verified on the battlefield. However, when the infantry entered the fight, the knightly cavalry (which had so far enjoyed a decisive advantage) began to lose its privileged position.

And the peculiar fifteenth and sixteenth-century renaissance of the custom of tournament skirmishes in the spirit of typical court entertainment was only "the goth summer of the era of knighthood" - aptly notes Frances Gies in The Life of a Medieval Knight .