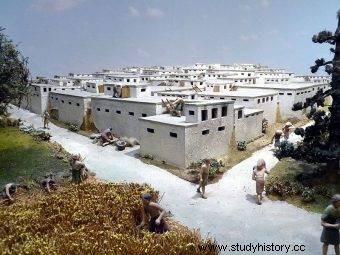

It is one of the oldest proto-urban human settlements, which still surprises with its size and, above all, its form. We invite you on a trip to Çatalhöyük - the ancient city of roofs dating back 10,000 years.

The world learned about one of the oldest cities in human history only in the late 1950s. It was then that British scientists led by James Malleart, conducting excavations in Anatolia, Turkey, discovered the remains of urban infrastructure from the 7th millennium BC. But that was not all. Subsequent works showed the scale of the find.

Çatalhöyük is one of the oldest proto-urban human settlements, which still surprises with its size and, above all, its form.

It is estimated that the settlement functioned from around 7400 BCE. It could be inhabited by up to 8-10 thousand people. It was thus the largest Neolithic proto-city center. At that time, Jericho had up to 2,000 inhabitants. It is worth noting that in the Middle Ages Polish castles, including Gniezno in the capital and then Kraków, did not have such a population.

So Çatalhöyük was a real metropolis at the dawn of human civilization. Researchers are still impressed by the form of this extraordinary ancient city.

Houses without windows, city without streets

The houses in Çatalhöyük were closely adjacent to each other. They had no doors or windows. They were entered via a ladder from the top, through the roof. And it was on the roofs that the metropolitan life of this fascinating center took place. There were no streets or town fortifications.

The whole city was built of building materials, and there was no shortage of them - dried mud. The average mud house was 25 square meters, so you could forget about the luxury , especially since up to 8 people lived inside, moreover, there was a stove, a hearth and a grain warehouse, which was a separate room. So crampedness was everyday life.

The average mud house was 25 square meters, so you could forget about the luxury, especially since up to 8 people lived inside

This is probably why life went on outside - i.e. on the roof, because the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük walked on the roofs, not the streets. If there were already "enclaves" at the ground, they were usually the remains of a demolished house. They were kind of "courtyards", although they were also used to dispose of waste.

Grandpa under the floor

The city without streets formed a kind of one large building. It also did not have a cemetery. This one was not needed. The dead were buried in their own homes - under the floor, in a fetal position, sometimes with a small number of items. So they were still "present" in the space where people lived, slept and lived every day.

According to the researchers, the fact of the proximity of the deceased and the burials of their next generations (in some rooms even several dozen remains were found) was the building block that united the community, emphasizing the common origin - the existence of a multi-generational "family".

The dead were buried in their own homes - under the floor, in a fetal position, sometimes with a small number of items.

Perhaps for hygienic or epidemiological reasons (which were realized?), Decaying bodies were not buried under the floor - only skeletons. Previously, corpses were exposed to vultures. The birds "cleaned" them from meat, leaving only the bones.

Some of the deceased were buried outside their homes - in places of great importance to the community, which served as sanctuaries. They are not distinguished by their size or the way of entering, but only by rich decorations inside. They consisted of various frescoes - from typically ornamental ones to pictures of animals, scenes from life and symbolic motifs. A popular "decoration" of sacred places were huge bull heads to which real horns were attached. Some of the frescoes also depicted vultures flying over the bodies. These birds were probably symbols of death.

The first wheat and the "mother goddess"

One of the oldest cities in the world arose in a place perfectly suited to live. The fertile plain yielded crops twice a year in a warm and humid climate. In addition, the local small river provided irrigation.

This is where the oldest wheat grains known to us come from - they are 8,500 years old. Probably the farmers of Çatalhöyük of that time used, as did the later Sumerians and Egyptians, irrigation to irrigate their fields. In addition, they cultivated, inter alia, chickpeas, peas, lentils. They collected almonds, raised cattle, which was their main source of meat. They hunted wild boar, fallow deer and deer.

Until recently, it was believed that a matriarchy ruled in the city of roofs, with the mother goddess as the main deity.

The people of Çatalhöyük were great craftsmen. They made weapons and tools - mostly obsidian, as well as decorative, possibly ritualistic items.

During the excavations, researchers found a large number of human figurines made of various materials. Many of them depicted female figures - often with corpulent shapes. On this basis, until recently it was believed that a matriarchy ruled in the city of roofs, with the mother goddess as the main deity. Today, however, this view is dismissed as simply an over-interpretation.

Revolution in paradise

Life in one of the first prehistoric cities was not all roses - the houses were cramped. The form of one large "building" and streets on the roofs did not allow for a change in living conditions. After a house was ruined, the same house was erected in its place. A major redevelopment would require the redevelopment of an entire block of interconnected apartments.

For about 2,000 years, however, this "city" and this community existed, and one of the binders of this group was precisely the buildings, together with the dead under the floor. Research by scientists indicates that the destruction of that world was not brought about by conquest, but most likely by the degeneration of the community manifesting itself in an attempt to break the existing rules, opposition to tradition and perhaps - beliefs.

The destruction of that world was not brought about by conquest, but most likely by the degeneration of the community, manifesting itself in an attempt to break the existing rules, opposition to tradition and perhaps - beliefs.

Researchers found that in the final period of Çatalhöyük's existence, houses were also built there separately, there were attempts to mark out streets. The buildings were decorated not only inside, but also outside. Are these traces of a revolution, a coup that took place there? There are many indications of that.

The shift in traditional patterns of behavior preceded the collapse of this community. It cannot be ruled out, however, that the revolution and collapse of this culture were provoked by natural changes - incl. drought caused by the rapid melting of glaciers and massive amounts of fresh water entering the Atlantic. It took place about 8.2 thousand. years ago. The result was a cooling down of the climate and droughts.

A study of the bones of the settlement's inhabitants showed changes in diet during this time. The population of Çatalhöyük has shifted to sheep and goats that are better able to withstand the water shortage. At the same time, traditional buildings collapsed. Separate houses began to appear in place of residential "clusters". Migrations in search of better living conditions have intensified.

All these factors, together with the end of cultivating the tradition that held the community together, resulted in its downfall.

Bibliography:

- P. Bieliński, Ancient Near East, From the Beginnings of Agricultural Economy to the Introduction of the Journal , Warsaw 1985.

- J. Grabowska, Polish archaeologists found a statue of a mysterious lady from before 8 thousand. years in Turkish Çatalhöyük, Gazeta Wyborcza (accessed on 7/27/21).

- J Grabowska, Thanks to Polish archaeologists, we know how one of the first megacities collapsed , Gazeta Wyborcza (accessed on 7/27/21).