There were only forty-six of them, but even the men admitted:they were the greatest asset of the Polish army and achieved successes which they themselves were completely incapable of. Why are they so rarely mentioned?

In the earliest days of World War I, hundreds of women supported the creation of human resources squads. Many also went to the territories annexed by Russia to organize supplies, sanitary services and agitation there, hand in hand with men. There were also some that were eager to fight in the front lines.

Initially, the volunteers' enthusiasm and their organizational skills were used with pleasure. However, when the structures of the Polish Legions began to solidify, Józef Piłsudski - a well-known misogynist and chauvinist - issued an order to "remove all women following the army."

Only one major exception was made. Even hard-core sexists admitted that the Women's Intelligence Unit was absolutely indispensable.

Words of appreciation

It was a small, inconspicuous formation with a total of forty-six women. It began to be created in the first days of August 1914, and also Józef Piłsudski (who, as a rule, spoke about women's service with a dose of haughtiness or even contempt) admitted that she had rendered him invaluable favors, completely disproportionate to her number.

Each of the intelligence officers worked for three, five or ten men. The girls took on the key duties on the one hand, and on the other - requiring great cunning, above-average caution, and often also ... special grace, completely inaccessible to gentlemen.

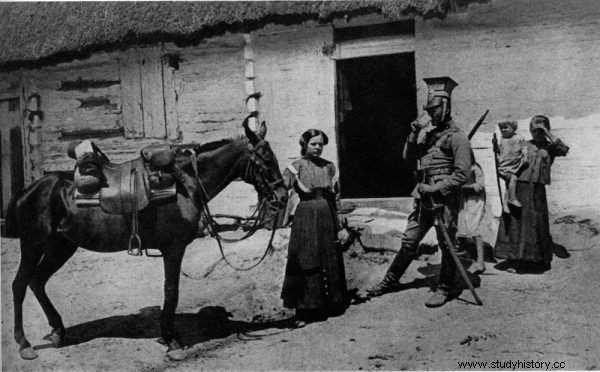

This is the only way men imagined the role of women in war:as helpers who were to bring, feed and water the horses.

In the first days of the war, the task of the Women's Intelligence Unit was to conduct strategic intelligence behind the enemy lines. The soldiers were to constantly monitor the Russians' moves and maintain contact with their troops, so that the entire forefront of the front, forty, sixty or even more kilometers deep, was well known to the commanders of the cadre troops.

"Great is the merit of my intelligence office, composed almost entirely of women, that I could then have data on the enemy," Piłsudski recalled years later. He claimed that the ladies served even "more selflessly" than his trusted cavalrymen. "On carts they crashed alone on all roads, making circles much larger than driving, because they extended to Warsaw, Piotrków and Dęblin," he wrote. He emphasized that, as a result, he could be "calm" about the position of his troops and that they would not be surprised by the Muscovites.

"True Hero Category"

The secret agents themselves could not even dream of a similar peace of mind. They were constantly exposed to meetings with the Russian military police. Seven female soldiers were indeed arrested, including two while crossing the front lines. This group included Wanda Wasilewska, the mother of the future midwife of the People's Republic of Poland.

Polish soldiers were also waiting for the front services of the allies. The command required women to hand over all reports to their superiors, never to the Austrians or God forbid the Germans. As a result, it often happened that the "allies" detained and imprisoned Polish intelligence women. One of them, refusing to disclose the obtained data, ended up in the crate for a long two months.

"Many of the couriers went through the front several times in such difficult conditions that when you read their memories or listen to their stories, you have the impression that this is not reality, but some fantastic fairy tale" - Wanda Pełczyńska said with appreciation years later:a politician and a deputy to the Seym of the Second Republic of Poland. And she knew what she was saying, because she was not only a part of the intelligence unit herself, but also reported directly to the Commander. After the fact, however, she preferred to speak about the achievements of her friends, not about personal successes. One could, of course, be accused of not being impartial. But there are many opinions similar to the one she formulated.

The legionnaire physician Julia Świtalska also emphatically wrote:"The service of women in intelligence is a category of true heroism." And by the way, she added, with optimism that turned out to be definitely exaggerated:"The names of these women in the history of Poland will probably be written in golden letters".

Techniques like from a spy novel

In everyday intelligence work, it was necessary to resort to often surprising steps to avoid the enemy's attention. Bronisława Bobrowska recalled that, for example, women were not allowed to carry backpacks, because although these would greatly facilitate long routes, they would also unnecessarily attract the attention of outsiders.

Members of the Riflemen's Association from Lviv. One can see, inter alia, the future intelligence officer Maria Rychterówna). Photo taken in 1912.

Another interviewee, Zofia Zawiszanka, emphasized the importance of the outfit, which could not look like a traveler, be neglected or excessively masculine. It was necessary to dress not even decently, but even - stylishly. This way it was easiest to play the lost lady, hanging around the front just because of her own carelessness and being lost.

Hotel stops were not allowed (the registration obligation exposed the courier who was looking for comfort to a quick exposure), you had to be very careful when renting horses and be able to lie as if you were stopped or searched.

Sometimes, in order to maintain the camouflage, an elderly female soldier, fifty or sixty years old, who could play the role of a "grandmother", was taken to the company. Then the younger courier took the role of the caretaker of a sick woman who urgently needed to get home or to her grandchildren with whom she was separated. When necessary, bribes were paid or… flirting with Russian soldiers.

Flirt, infiltration, manipulation…

For example, Maria Rychterówna proudly told that during one of the missions she turned an enemy officer so dizzy that he did not even notice, and had already signed her a pass authorizing him to travel. "Oh men, the masters of the world!" - she was laughing. The aforementioned feat pales in comparison to the achievements of another interviewee, Maria Korśmieowiczówna.

A whole squad of men more frightened than one woman? There was much more truth to this propaganda drawing from 1915 than its author believed ...

Once she had to cross a vast lake. Instead of asking the peasants for help and risking being exposed, she decided to use not just one Russian soldier, but their entire unit. She charmed the privates stationed nearby and persuaded them to ... get a boat for her themselves and bring her to the marina. In return, she promised an innocent but romantic ride on the lake. She kept her word, then stole a boat at night and swam to the opposite bank.

She had a different way of dealing with the officers. She mastered their pity. For example, she was able to convince the general adjutant that her friend's family was stuck on the German side of the front and required urgent help ... The man not only believed in the bleak story and stamped the documents, but even assigned the agent an escort. Nay! He ordered one of his men to carry suitcases for Maria.

The female intelligence officers were expected to have an excellent, photographic memory. They were to take care not to confuse a single number of the encountered Russian regiments and not to misspell any of the recorded names or terms.

Leaving physical marks should be avoided whenever possible, so reports often only existed in the heads of female soldiers and were recited orally. Sparse documentation was prepared in accordance with the regulations of the espionage service. The messages were marked with a fine typeface on narrow blotting papers or with invisible ink on special towels; the latter solution was provided to the girls by their chemist friends.

Commandant of the intelligence

Aleksandra Szczerbińska - the future wife of Piłsudski, an experienced conspirator, and from mid-September 1914 the unit commander - left a lot of information about the intelligence service.

From Aleksandra's notes, we know how the tasks of the soldiers changed and expanded, and how various successes were owed to them. She emphasized that when "all communication with Warsaw was interrupted, then the couriers of the Intelligence Department established this communication". According to the future Mrs.

They reached not only the capital of the Russian partition, but also Minsk and Odessa. Not only did they collect invaluable military data, but when needed, they also moved blotting paper, transported explosives and passed on news and orders to independence organizations emerging on the other side of the cordon.

Aleksandra Szczerbińska in a portrait photo from 1919

Their merits are hard to count. Nevertheless, the members of the detachment were treated in the same way as all other women who wanted to actively fight for independence. While they performed key functions, they were gradually marginalized and cut off from information.

Finally, on March 25, 1914, a completely unjustified (and devastating) decision was made to abolish the women's intelligence service.

Shameful Decision

The order was officially signed by the Austrians, but the commander of the first brigade, Józef Piłsudski, did not defend his soldiers at all. The interviewers bitterly commented that they had just lost the last "kind of service available to them". Those completing the missions were not even allowed to deliver the reports to the destination. They were to hand over everything to their colleagues.

The women sent out protests and asked to be transferred to the troops fighting on the front lines. An application in this matter was made, among others, by Aleksandra Szczerbińska, demanding admission to the sappers unit. Piłsudski not only "strongly opposed this", but also threatened to remove malcontents from any organizations associated with the legions.

Most of the women who wanted to continue helping the cause, even if they stayed behind, were forced to accept shameful decisions. However, not every soldier has come to terms with the decisions of the great sexist. There were those who were going to fight no matter what. Even if they had to become men to do so…