If you've just been captured, it doesn't mean that the war is over for you, your name won't be in books or Wikipedia. Just remember a few rules. Look forward to bombs and rainy days, do not neglect your gymnastics and ... keep your English phlegm!

Imagine you are an English gentleman and military officer of the British Empire fighting against the Axis Powers on three continents and three oceans. You certainly expected a solid dose of adventure. And some stupid bondage won't take it away from you!

Take, for example, Lieutenant General Adrian Carton de Wiart. This sixty-year-old, hero of several wars, was taken prisoner by the Italians in April 1941. The incident took place in North Africa. And it is worth using the general's experience.

1. Look for opportunities before you're in camp

I waited for the bomb to finally hit our ship, which would give some chance to escape in the ensuing commotion. The ship finally filled with prisoners and we set sail for Naples, hoping that one of our submarines would sink it along the way. Unfortunately, none appeared - complained the British general in his memoirs entitled "My Odyssey."

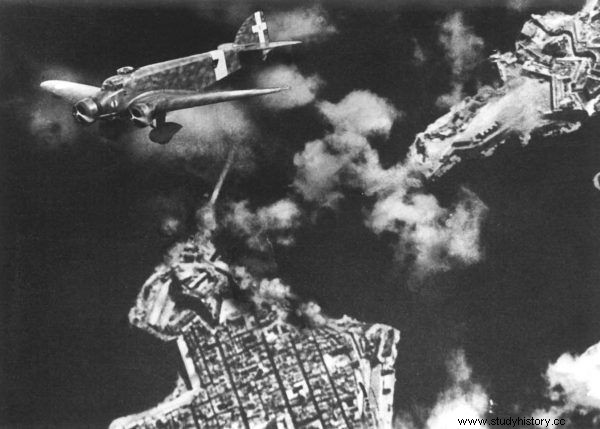

De Wiart dreamed that the RAF pilots' ship carrying him would bomb. Unfortunately, nothing like that happened. But the Italians - as you can see in this photo - bombed Malta. The photo is from the book "My Odyssey" (Bellona 2016).

However, think positively - if you did not manage to escape right away, maybe this trick will be successful a bit later. After all, Italy is not Siberia, and Siberia managed to escape.

2. Find out where you stand

It was only when I was locked in a cramped room that I felt that I was trapped and realized that I was a prisoner. (...) I was on the verge of despair - mentioned General de Wiart. But it's generally not bad. You are protected by international regulations - the Geneva Conventions of July 29, 1929, which made the fate of prisoners more humane. The Germans, and later the Japanese, often broke this law, so be all the more glad that you ended up in the hands of the Italians.

They will feed you, you will get food packages from the country through the International Red Cross. In the camp you will have many friends and even an orderly! It is possible to survive.

3. Be ready

Everyday life in a POW camp consisted of small things. There were appeals, meals, walks, but in fact, as de Wiart rightly claimed, hours drag on, but weeks pass quickly and you need to grab a specific idea or start striving for something so as not to be demoralized . You can, for example, deal with ... breeding rabbits. If only you wouldn't discourage them from copulating like one of the general's colleagues.

It's also worth taking care of your physical condition: I exercised every day - recalled in "My Odyssey" the general - [and I saved] my energy for intensive marches. He was right. Your freedom may be in your legs, so be prepared when the dawn of freedom rises for you. It is also worth practicing rappelling just in case - the example of de Wiart (who had his limb amputated years ago) shows that it can be done with one hand!

4. Have a plan

You know what's going on. You want to get home, and the road there passes through neutral countries - Sweden, Switzerland, Spain or Portugal. So you need to prepare a plan on how to get there, what you need to do and how to avoid adversities.

It's worth talking to your colleagues, but you should definitely not write down your ideas on paper. And if you make this mistake, make sure you have a really good hiding place. In the event of a revision, finding such arrangements may result in a dump. And the guards can even find them under the tiles.

5. Figure out how to get outside

Your camp is definitely in a place that makes it difficult to leave, protected by barbed wire, sentries and searchlights. More important prisoners of war are often honored with a camp in a castle - picturesque, but on a rock, high above the river. Neither undermine nor drop onto the rope.

The place of imprisonment is really beautiful, but how do you get out of there? This question was asked by de Wiart at the Vincigliata castle in Tuscany (photo:Sailko, license CC BY-SA 3.0).

Some prisoners prefer improvised actions. Maybe you can look cheeky? Maybe you are similar to one of the guards? Maybe some of the colleagues will disguise themselves as guards and take a few prisoners outside under the pretext of deratization of the rooms? Maybe they'll take you to the dentist or to an interview outside the camp? Why don't you jump into an exiting truck?

In Colditz, Germany, the two British pilots even prepared a glider out of bed elements, floor boards, electrical cables and duvet covers. In the Sagan camp (now Żagań) they took advantage of the fact that the Dutch and German flight uniforms were almost identical. Or you can sacrifice the sheets and twist a rope. You've certainly seen this done in the movies.

It's not possible? It's hard, you have to consider longer preparations. For example - digging a tunnel.

6. Roll your hands to work!

It is best to work in a group, e.g. in an escape committee with more prisoners. Each of them can contribute to the cause of escape. They have different work experiences, ideas and talents. It's worth taking advantage of. Especially since the tunnel is just the beginning.

Maybe the prisoners were not able to dig such a tunnel with broken knives and crowbar, it did not cut their wings to keep trying. Even if they dug a centimeter a week. The photo shows the tunnel leading to the Gaza Strip (photo:Marius Arnesen, license CC BY-SA 2.0).

You'll need some digging tools - General de Wiart and his colleagues had only a few broken kitchen knives and a small crowbar. For seven long months, at least four hours a day, they dug, drilled, hammered and carved their way to freedom. They moved forward a few meters in a good week, and a few centimeters in a bad week. Just remember to jam the sounds of underground work and discreetly hide the excavated soil.

7. Use white intelligence

It is worth reading the press. Their own does not reach it, because it is forbidden, but even in the hostile one you can find useful information. You will learn what city was bombed - it is worth avoiding it, so as not to get stuck there by the broken communication lines.

You don't count on borrowing a map from an enemy, but you can make your own. If they let you leave the camp, or if your friends have already tried to escape, they must have seen a few things, e.g. where is the road, which way to the station or where the posts are.

8. Gadgets

They took your weapons, you are not allowed to have money, civilian clothes, maps, compasses, flashlights or backpacks, but the motherland cares for you. She has even set up a special Intelligence section - MI9 - to assist prisoners who wish to break free.

Plain pencil? Or maybe after breaking it it will turn out that this is just a cover for… a compass. That's not what MI9 did (photo from Concord Museum by Daderot, source:public domain).

Hence, in the parcels sent to the camp, you will find useful gadgets, e.g. envelopes with maps and banknotes embedded in gramophone records, pipes and pencils with built-in compasses. Pipes could be smoked, pencils had to be broken in the place marked with the first letter of the manufacturer.

Besides, get interested in card and board games. Cards were often wrapped with a special durable tissue paper prepared especially for drawing maps. In games like "Monopoly", real banknotes were hidden among those used for fun, and in figurines elements for building a radio. Also valuable were the addresses of nice people from the Underground written in sympathetic ink on packages of soup cubes. They can give you accommodation, civilian clothes, arrange guides.

It was also worth having your own gadgets - such as a bamboo cane, inside which General de Wiart hid banknotes. Later he sewed them up in his fly. If something was missing, maybe the sentries have it. For the coffee or chocolate you got in packets, you could get almost anything from them.

You have to stockpile your own food supplies for your hike. The best for long walks are tinned beef, rusks and chocolate.

9. Take care of documents and foreign languages

You cannot be allowed to be picked up by the first patrol just because you cannot show the document. For example, an artistically talented prisoner-mate can help, who will produce an almost identical document based on a document that has been stolen from someone, but with your (or one similar to yours) photo.

My double looked like a gloomy thug, but the rest found the resemblance striking de Wiart complained, but at the same time proudly declared to the Italians: I'm not going to learn your goddamn language! But remember that not everyone speaks English.

"My doppelganger looked like a sullen thug, but the rest found the resemblance striking." And what do you think about it? Photo of de Wiart from 1944, taken by Cecil Beaton (source:public domain).

Once you escape from the camp, even if you have a companion who has learned to speak the native language, try to avoid them anyway. They still talk to you and then what? Don't run away in uniform, especially in a Scottish kilt! A colleague who knows how to sew is priceless. It will help you sew clothes to look like simple workers or farmers, and a backpack.

10. Be discreet

The key is the weather. It is best to choose a rainy, windy night, during which ghastly howls and whistles in the castle, because the guards will not want to lean their nose beyond the guardhouse. After leaving the tunnel, it is worth masking its exit opening. Why should the guards wonder where a large hole suddenly appeared near the camp. This gives you time to move away from the place of your torment.

11. Don't stare at sites

I took a deep breath and suddenly felt like I was three times taller! We were free ... and freedom is a priceless thing (...). At that moment, I had its unique taste in my mouth - mentioned General de Wiart. But don't let this dizzying surge of endorphins lull you into vigilance.

The escape of de Wiart and O'Connor was foiled only by the intuition of the carabinieri. But for them it wasn't the end of the world at all. General Richard O'Connor in the photo. The photo is from the book "My Odyssey" (Bellona 2016).

Gen. John Combe, who escaped the same night as Gen. de Wiart, was captured the next day. Only because he was staring too hard at the shop window on a street in Milan. On the other hand, those who were careful and escaping in the two, General Adrian de Wiart and General Richard O'Connor, lost only the intuition of the Italian carabinieri, who demanded their documents and something began to "stink" to them. They were in the wild for eight days.

12. Still worth a try

Remember, running away is not only important to you. Each successful attempt also lifts the spirits of colleagues in captivity. And think how happy they will be to send them greetings from London through the Red Cross! You can also think about sending greetings to the camp commander, although he is unlikely to share the enthusiasm of your colleagues.

If you fail, your friends will admire you anyway, and fate is sometimes kind. The Italians freed Gen. de Wiart by themselves. Six months after the unsuccessful escape, they asked him to fly with their representative to London to negotiate the terms of the Italian surrender.