Stefan Rowecki received reports from Witold about the killing of Soviet prisoners of war in gas chambers in the fall of 1941. The commander-in-chief of the ZWZ, like Witold, was not entirely sure what to do with them. He understood that the behavior of the Germans was certainly contrary to international law. However, Rowecki did not combine the new methods of killing with the brutal occupation policy conducted in Warsaw.

The Germans placed the 400,000-strong Jewish community of the Polish capital in the narrow streets of the ghetto, where thousands of people died of hunger and disease every month. Moreover, Rowecki's people informed him that the Germans were liquidating entire Jewish communities in the territories of eastern Poland occupied by the Nazis. However, Rowecki saw isolated cases in these incidents, and not the beginning of a broader campaign of mass murder.

The use of gas to eliminate a certain group of Auschwitz prisoners seemed to be a one-off event at the time, and Rowecki's comrades assumed that they were dealing with a test of a new weapon before its use on the fronts. Information about the expansion of the camp for prisoners of war could mean that the Germans wanted to use the Soviets as slaves providing free labor, just as they did with the Poles.

The report's journey to Sweden

Rowecki handed over Witold's written reports to his best courier, Sven Norrman , a fifty-year-old staid Swede who ran a Polish branch of a Swedish electric company in Warsaw. Norrman could not stand what the Nazis did to the city that had become his second home in recent years, and believed that it was his duty as an "outsider" to tell everyone about what was happening in the Polish capital. / P>

Due to the fact that Sweden remained neutral, he could travel freely between Poland and Stockholm, which made him an ideal courier. Rowecki regularly met Norrman at Elna Gistedt's cafe in Nowy Świat, where they could always count on the hostess' discretion and a decent meal thanks to the good supply of black market products, as well as secretly served beer in paper cups.

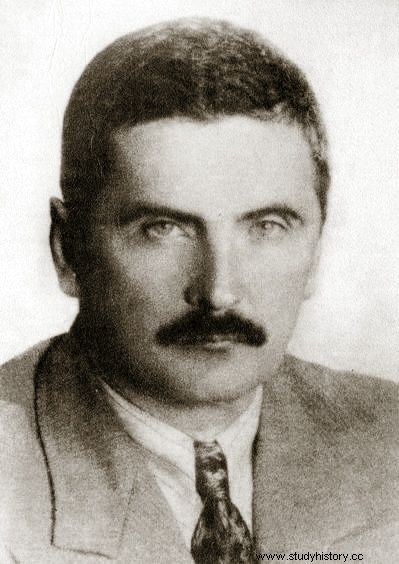

General Stefan Rowecki (1895-1944) - Polish commander, officer of the Polish Army, commander-in-chief of the Home Army

In mid-November, Norrman left for Berlin. He took with him a report on microfilm, sixteen and thirty-five millimeters wide, hidden in a double-bottomed suitcase. The technique of recording data on microfilm was developed before the war. A single roll contained two thousand four hundred pages of text, which could not be read without specialized equipment, which, if caught, gave the courier some time to react.

On the train, Norrman, in conversation with his fellow travelers, loudly praised the actions of the National Socialists. He reached the Tempelhof airport in Berlin without any problems. There he boarded a flight to Stockholm. There was still a Polish diplomatic mission in the Swedish capital, despite the fact that the Germans pressed hard for its removal.

Probably Norrman donated the microfilm to the Poles working there. This important package was then transferred to a secret facility far north in Norway, from where it ended up at Leuchars Air Base near St Andrews on the Scottish coast. From there the report reached London, where the British were the first to deal with it. Władysław Sikorski at the Rubens Hotel, where his headquarters was located, received it at the end of November.

What do the British say?

The report reached London just as the British were thinking about how to react to the news of the crimes committed by the Germans in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union. The immediate threat of an invasion of Great Britain was over, and while Luftwaffe planes continued to terrorize British cities, the bombing became less intense. The Londoners shyly began to say that the worst was over, but Churchill knew the fate of the war was still hanging in the balance.

"There is no respite week; Hitler's firing squads are not idle, bringing death in numerous occupied countries, ”Churchill said in a radio speech on May 3, 1941. - “On Mondays [Hitler] kills the Dutch. On Tuesdays of the Norwegians. On Wednesdays, he shoots French or Belgians. The Czechs must suffer on Thursdays, and now the hideous schedule of executions is also completed by Serbs and Greeks. Poles are dying all the time, day after day. ”

Such public appearances by Churchill followed the established narrative of the brutal repressive measures employed by the Germans. Their primary task was to maintain the will to fight Hitler. However, Churchill was well aware that the opening of a new front in the east in June 1941 also meant a disturbing change in the nature of the Nazi atrocities.

British cryptographers from Bletchley Park intercepted messages sent by the Germans via Enigma, a text-encoding cryptographic machine using special rotors. The Germans were sure that the Allies were unable to break the Enigma cipher, and they rarely changed its settings. Polish intelligence managed to secretly make a replica of an early version of the encryption machine that was shipped to Great Britain in 1939. In late June 1941, cryptographers began intercepting encrypted radio messages sent by the Orpo militarized police units to Berlin with data on the huge numbers of Jews shot in the East along with partisans and so-called communist sympathizers.

Winston Churchill “[Hitler] kills the Dutch on Mondays. On Tuesdays of the Norwegians. On Wednesdays, he shoots French or Belgians. The Czechs must suffer on Thursdays, and now the hideous schedule of executions is also completed by Serbs and Greeks. But Poles are dying all the time, day after day. ”

The messages decoded from the ciphertexts seemed so shocking at first that they raised the doubts of surprised analysts."Of course it is doubtful that all those murdered who have been identified as Jews really were Jews," argued one analyst. “Many were undoubtedly not Jews; and yet the fact that such large numbers appeared may be the basis for assessing that these executions were carried out with the knowledge of the highest state authorities. "

An unbelievable genocide

At the end of August 1941, Churchill finally understood that the Nazi anti-Jewish campaign could not be compared with anything else because of the unprecedented number of deaths. However, like General Rowecki in Warsaw, Churchill did not admit to himself that what was happening was happening is just genocide. He knew the assumptions of the strategy of Nazi actions towards German Jews, defined even before the war. After all, Hitler threatened that the Jews would pay for the war he had caused.

But Churchill was unable to see the connection between racial politics in the Third Reich and what was happening in Russia. In a radio speech on August 25, BBC listeners heard that “German police forces are carrying out tens of thousands, literally tens of thousands of executions, murdering Russian patriots who are defending their homeland. (...) We are witnesses of a crime on an unprecedented scale, a crime that is hard to define. "

This speech sparked comments that made headlines, but on this occasion it proved how difficult it was to draw the audience's attention to the suffering of the victims. Churchill's failure to emphasize that a large proportion of the Europeans murdered by the Nazis were Jews was probably intended to conceal the origin of the material. At the same time, this silence resulted from the attitude of some government officials who preferred not to play on anti-Semitic sentiments in the UK. This approach mainly reflected their own prejudices.

The chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee, Victor Cavendish-Bentinck, was highly skeptical about intelligence on Nazi crimes, even though he was one of the few members of the government administration with direct access to decrypted cables from the German police. When he received information from Soviet sources about the massacre of thirty three thousand Jews carried out in the second half of September in the Babi Yar gorge near Kiev, he called this report "a figment of the imagination of the Slavs" and recalled that Great Britain during World War I "spread for its own needs false rumors of atrocities and atrocities of war." He finally stated, "I have no doubt this is a very well known game." He believed that the Nazi crimes - if there were really any Nazi crimes - would be best investigated after the war.

Source:

- The article is an excerpt from the book Ochotnik. The true story of Witold Pilecki's secret mission . Ochotnik is the long-awaited story of Witold Pilecki, which has just been released on the market by Znak Horyzont Publishing House in cooperation with the Pilecki Institute. The book is held under the patronage of Historical Curiosities