After the outbreak of the November Uprising, Grand Duke Konstanty was surprised by the development of events and was forced to leave the Kingdom of Poland, of which he was the actual ruler. On December 13, he crossed the border with the Empire. He never returned to Warsaw, although he cried when he left. Why?

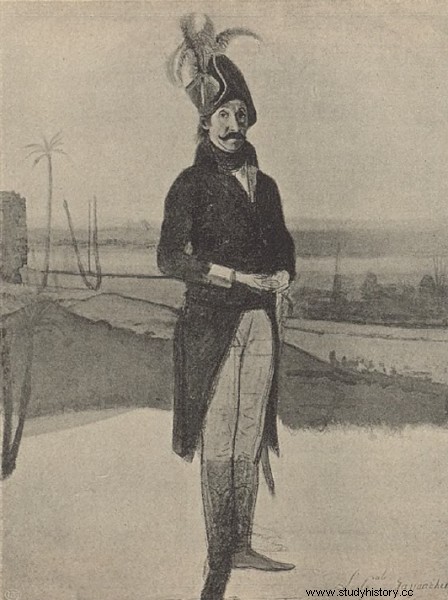

Konstanty Romanow, younger brother of Tsar Alexander I and heir to the throne at the time, formally began his reign in Warsaw in 1815 after the proclamation of the Kingdom of Poland at the Congress of Vienna. He was officially an army commander, but in fact he held power throughout Congress.

The tsarist governor - General Józef Zajączek - did not make any decisions, without first obtaining the approval of Konstanty. The Grand Duke, however, kept up appearances and (at least theoretically) recognized the sovereignty of the governor:during state ceremonies, he gave way to the general, and on each anniversary of the establishment of the Kingdom, shortly after the end of the parade, he went to Zajączek to express his wishes to him.

Polonophile or ... Pole Eater

Konstanty loved the military with all his heart and considered himself a soldier. After settling in Warsaw, he started training the Polish army - exercises were held in Saski Square every morning. Varsovians and visitors used to go there to watch this unusual show, "admired this accuracy, which could not be compared with anything else, as with a machine that moves puppets" . After some time, foreign princes and generals began to come down to the Vistula River to watch this extraordinary spectacle, and Romanov, listening to loud praise, proudly replied:"My students!".

Thanks to his involvement, the army's budget was half the budget of the entire Kingdom. The military had the best equipment available. The Grand Duke also ordered a swimming pool to be built and invited trainers from Austria. On his initiative, the fortresses located in the Kingdom were modernized and several military schools were established.

The tsarist governor - General Józef Zajączek - did not make any decisions, without first obtaining the approval of Konstanty

Unfortunately, the Grand Duke was also a rash man and often cruel - he could sentence a soldier to a flogging penalty for ... an uncleaned button. It should be emphasized that both Poles and Russians suffered from the outbursts of Konstanty's anger. Once he ordered a Russian unit to go on a trip on a frosty winter night, as a result of which 500 soldiers had frostbite on their legs.

Romanov also loved Warsaw life. He traveled to St. Petersburg rarely and reluctantly. He finally sealed his relationship with Poland by marrying Countess Joanna Grudzińska in 1820, who received the title of Duchess from Łowicz after her marriage. It was not without sacrifices - to marry his beloved, he had to divorce his wife, overcome his mother's resistance and give up the crown for the younger brother, Mikołaj.

However, he did not regret it. He was very happy with Joanna. This is best evidenced by his own words in a conversation with the head of Zamojska. Konstanty then pointed to his wife and said:"This woman I adore (...), she is all my happiness".

Beginning of end

In 1830, Konstanty was repeatedly informed about the possibility of a revolt. But he was sure of the loyalty of the Polish subjects, so he paraded around the city without escort, and appointed only war invalids armed with sabers to act as guardians at the Belvedere.

For Joanna and Konstanty, November 29 did not differ from hundreds of others. The attack on the palace came as a shock to them. The insurgents wanted to murder Romanov but his butler was quick to lock his boss's room.

By the morning of November 30, practically all of Warsaw was in the hands of the rebels. Although units loyal to Konstanty were brought to the Belweder Palace, the location of the building made it impossible for them to concentrate effectively. Under these circumstances, the spouses were advised to leave the residence and go to Wierzbno - the property belonging to the Grand Duke's friends. Russian officials and their families also left with the Grand Duke and his wife.

The Grand Duke did not decide to suppress the uprising, hoping that the insurgents would come to their senses.

In Wierzbno, Joanna and Konstanty lived in a one-window room, all of which consisted of a table, a few chairs and a wide Turkish sofa. The others crowded into one room, where they slept on straw on the floor. The fugitives were still hungry, the only dish they were served was soup.

All the time people wondered what to do with the revolted population. The Grand Duke did not decide to suppress the insurgency, hoping that the insurgents would come to their senses. "Poles started, let the Poles stop!" He repeated. Meanwhile, members of the Administrative Council of the Kingdom came to Wierzbno and demanded from Romanów "immediate military action". Angela Pienkos, Konstanty's biographer, believes that the Emperor's failure to act was also due to "his fear of bloodshed".

The Duchess of Lowicz, who had never interfered in politics before and accepted all the decisions of her spouse, did not agree with the behavior of Konstanty. When the aforementioned delegation arrived in Wierzbno, Joanna took part in the meeting and - as the witnesses of the events described - "in the vivid, dangerous future of the painted colors, she called them [guests - editor's note]. aut.] with the most tender words, that they would like to alleviate this whole excitement ”.

When the Grand Duke decided to withdraw from the Kingdom and release the Polish troops loyal to him from his oath, she did not hide her opposition and called for the suppression of the uprising.

"They don't know how much I loved them"

On December 4, 1830, Konstanty, along with his entourage and faithful troops, began his journey across the Bug River. Before the Russians left, the Grand Duke sent the following declaration to the Provisional Government:

I am leaving the Imperial Army and departing from the capital. I trust the generosity of the Polish people that my army will not be disturbed during the retreat. I entrust the national protection of buildings, the property of various people and their lives.

When leaving Wierzbno, Romanov cried. The reason was the feeling of bitterness that the Poles had betrayed him, a man who trusted them immensely. Konstanty was heard many times whispering:"They (Poles - author's note) do not even know how much I loved them!".

The column consisted of Russian military units and about 100 carriages with civilians. Tired soldiers moved slowly, carriages were often stuck in mud. Oftentimes, travelers' only meals were bread and beer; their clothes were wrinkled and dirty. They spent their nights in unheated country huts. Nevertheless - as Duchess Nadezhda Golitsyn relates - Konstanty cared for the comfort of his companions in misery, sharing his arguments with them. The duchess, on the other hand, tried to support other women, although at times she was so embittered that she was unable to control her emotions.

On December 13, the "procession" crossed the border between the Kingdom and the Empire. Konstanty and Joanna stopped in Witebsk (now in Belarus). Nicholas I invited his brother and his wife to St. Petersburg, but the Grand Duke was reluctant to leave, not knowing what kind of reception his countrymen would prepare for him in the capital after such a painful fall - and whether he would be able to look into the eyes of those Russians whose sons had died during the uprising.

Konstanty died of cholera in June 1831. He was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg. After his death, Joanna moved to Tsarskoye Selo, where she was surrounded with love and respect. She closed her eyes for the last time on the first anniversary of the November Uprising.

Bibliography:

- Lelewel, Bratkowski, Delegated to Wierzbno on December 2, 1830, Printing House of the Widow Gichard Ainé, 1832.

- Pienkos, The Imperfect Autocrat Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich and the Polish Kingdom , Columbia University Press, 1987.

- Wiernicka, Polish women who ruled the Kremlin, Bellona, 2018.

- Wiernicka, Russians in Poland. Time of partitions:1795-1915, Bellona, 2015.