The Republic of Poland lost not only the rank of a superpower, but even an independent country. The shameful treaty forced the Polish king to pay the Turkish sultan on a permanent basis. And it would probably have been so, had it not been for the great victory of Hetman Sobieski. The man who was about to put on the crown himself.

In October 1672, proud and confident of their strong position, Turkish Chaushas and depressed envoys of King Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki, depressed by a long journey, came to Buczacz for talks. The latter had been watching the country depopulated and devastated by the invasions of Tatar czambuł for many days.

The terms of the negotiated deal turned out to be very strict. The Commonwealth was losing Podolia and Ukraine and undertook to pay the annual tribute (the documents say:a gift for the Sultan) in the amount of 22,000 thalers. This tribute aka gift reduced the state to the role of the Port's vassal.

The Seym of the Republic of Poland did not accept this dictate. The peace treaty has not been ratified. There was also no illusion that the Turks would be willing to keep the peace. On the contrary, the threat of aggression by the sultan's empire hung over the country. The war seemed certain, and one man could ensure success - Hetman Sobieski.

A fragment of a painting by Adam Setkowicz "The Battle of Chocim"

The talents of this commander, who combined a love of antiquity and knowledge of the achievements of ancient leaders, with the experience gained during a long episode of service under the watchful eye of King Charles Gustav, seemed more needed than ever before. The war resumed, and the hetman set off at the head of an army of over 50,000 to attack the Turks manning the dangerous, until recently Polish fortress in Khotyn on the Dniester.

Read also:Husaria - we bust the myths!

The whole day was digested in frolics

Near Chocim, on the huge meadows on the Moldavian side of the river "by a cannon shot from the Turkish camp", the Polish cavalry banners lined up in combat order . The sun was below the horizon, and since November 9, 1673 was cloudy, the gray tire of fog and rain limited visibility. Nevertheless, thanks to the torches and axle boxes with tar, the companions under the hussar and armored signs could see the outline of a high embankment, which stretched from the Dniester shore with a broken line of bastions and blurred somewhere under the dark patch of the forest.

The extraordinary movement lured the soldiers of the Ottoman Empire to the entrenchments, so that it was a custom that was often practiced by insults from the Polish side, then from the Turkish side. Immediately after the insults, the calls to fight flew towards the Turkish trench . Alarmed by the tumult, the Turkish commander, Husejn Pasha, a Beglerbej (and therefore the governor) of the Sylisters, left his delicious tent. He was handed the horse and, together with the retinue of advisers, set off on the embankment to personally assess the situation. As soon as he found out that the giaurs - as dissenters were called - were indeed close, he ordered to beat them with cannons.

Meanwhile, Poles, ignoring Turkish bullets, still waited for the entire Turkish power - estimated today at over thirty thousand soldiers - or only skirmishers. The latter did indeed go into mock combat. A few, maybe a dozen or so riders went beyond the line of fortifications, and from the Polish ranks a group of skilled fencers, mainly from light banners, quickly ran towards them. "The whole day was consumed in frolics," wrote the chronicler, "in which only two Poles and four Turks were slaughtered," and then, when it was completely dark, both sides returned to their positions.

While the cavalry began a verbal duel with the Turk, infantry regiments and artillery arrived at Khotyn. The cavalry, sheltered by banners, returned with columns behind the old embankment that remembered the times of Sultan Osman II, who unsuccessfully drew the Polish rampart before half a century in September 1621.

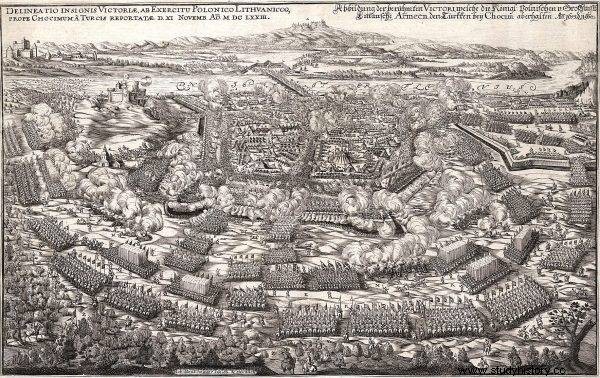

17th-century woodcut depicting the Battle of Khotyn.

Regiments were set up according to the custom. Behind the embankments from the enemy's side stood infantry and artillery. On the sides of the dragoons, light cavalry, then armored, and finally hussars. The tent of the Grand Hetman of the Crown, Jan Sobieski, was placed "in the back line, between [h] usarzami". A square was marked out around it, and from the square there were avenues so wide that four horses could pass each other. All this to quickly gather flags and launch them to counterattack in an emergency.

Skirmishers and banners descended behind the embankments. There was silence in the field between the camps. The cries of the pedestrian and horse guards were heard only time and time again. The camp was on the alert. The company laid out along the alley, ready at any moment to jump at the command of the queen.

Meanwhile, the Hetman welcomed guests in his tent. All senators and magnates gathered here for a conference. There were also field hetmans of the Crown Dymitr Wiśniowiecki and field hetmans of Lithuania Michał Radziwiłł , Sobieski's brother-in-law. Marcin Kątski, general of artillery, and Stanisław Jabłonowski, the crown guard, were kind to Sobieski; but there were also some unfriendly ones. The great Lithuanian hetman, Michał Pac, looked askance at Sobieski's star rising above other senators. It was not a secret for the army or anyone in the Commonwealth that both hetmans did not like each other.

After the deliberation, Sobieski went outside the tent. In the distance, visible in the glow of burning torches and axle boxes, the huge mass of the Khotyn castle, a mute witness to the glory of the Polish army, was soaked in the cold rain. Glory seemed long gone.

Read also:Połonka 1660. Forgotten triumph

First charge

November 10th got up as cold as the previous ones. It was raining and snowing. From dawn, the company gathered in banners and rode outside the camp, taking the place marked by the banner during the night council. In the first line, general Kątski's infantry regiments and artillery. In the second, ride. On the right, south wing it is crowned, i.e. Bidziński, Jabłonowski, Sobieski, Wiśniowiecki and Potocki. In the left west, Lithuania. First, hetman Pac, a little to the north hetman Radziwiłł. The privilege of playing the overture went to Marcin Kątski. All along the line the cannons rang out.

Husejn Pasha did not intend to release his troops either on the frolics or under the blows of the unpredictable Polish cavalry. He believed that he was in a better position than Sobieski. His army of 30,000 occupied a well-fortified position. Eight thousand Janissaries - elite infantry - should stop the assaults of the regiments of foreign and Hungarian infantry. And at the same time he had artillery, which had just started a cannonade.

The roar of the cannons echoed over the fields and did not stop, while the envoys from Wallachia showed up in the Polish camp. It was a strange message. Wallachians and Moldovans asked to attack their rampart, which was located on the southern side of the Turkish camp, almost at the Dniester. Explaining themselves, they said that they wanted to use the Polish attack as an excuse to switch to the side of the Republic of Poland. The request was granted at about 10 o'clock. The assault was successful. Infantry, as well as the Polish and Lithuanian artillery, occupied the Multański trench together, gaining an excellent firing point for the Turkish ramparts that were weak from this side. Sobieski left the Wallachian and Moldavian banners in reserve behind the right wing.

The betrayal of the Wallachians tilted the balance of forces definitely in favor of Poland. However, it did not add quality to Sobieski's army. The Moldovan and Wallachian banners were famous for their frequent change of fronts, and no one treated them as a serious ally. Meanwhile, the infantry was attacking. Along the Dniester, passing through the old Wallachian camp, attacked by the "camp crowd" commanded by Colonels Jan Dennemark and Jan Motowidda, a man "very conscious of the war game, who recently got out of Turkish captivity, now supposedly avenging [for years] a heavy prison, was severely against the Bishurman nation."

The Janissaries were the elite of the Turkish army.

Motowidło hurried too much and set off for the assault before the pre-arranged signal, i.e. a cannon shot, allowed it to begin. They got to the embankments. Grenades flew, heavy balls with a smoldering heat in a paper sleeve. Before they exploded, a volley of muskets was fired and the camp people threw themselves on the ramparts with sabers, rapiers and berdysh. “To the south, the fight was balanced; both armies were separated by one embankment like a tableware that stopped the other side, ”wrote Kochowski. The assault caused significant losses to the Polish-Lithuanian army, but it did not break its spirit. 17 officers were killed, and colonels Motowidło and Dennemark were also killed. "I do not know whether this incident should be called a failed attempt," wrote historian Tadeusz Korzon about the failure of Motowidła's assault. - "Maybe Sobieski needed her to properly address the blow to the resistance force."

For a pistol shot

In the afternoon of November 10, nervous hours began for the Grand Hetman of the Crown. News came from the driveways that the enemy was crossing the trains across the bridge leading from the Turkish camp. At first it was thought that Turczyn was withdrawing, but after thorough reconnaissance it turned out that Husejn Pasha decided to send carts to Chocim, and he decided to do so in order to make more room for the army in the camp's yard . This reassured the queen. He already knew that the enemy does not escape from the traps they set.

All evening and night, the Crown and Lithuanian armies did not leave the line. "Over precipitous ravines and sticky mud" infantry and artillery moved their guns to a new location. The entrenchments were made "already within the distance of a musket shot by the enemy ramparts." The engineering work, to use the elegant term for digging in dirt and mud, was watched over by all the banners of the cavalry. The chief was also on guard. Hetman Sobieski did not give in to the temptation to sleep. On a frosty, windy night, flogged with rain and snow, he wandered around the army and raised morale. He talked, advised, then sat down again, exhausted.

The Battle of Chocim in the painting by Franciszek Smuglewicz.

They waited for an order to storm, but the chief hesitated. As the hours passed slowly, the riding banners were still in impeccable formation. Only artillery thundered, covering the Turkish camp with iron grenades. The Turks bit back the Poles and the Lithuanians, so the roar of the cannons was hovering over the battlefield of Khotyn. Soon Hussein Pasha was happy to repel the assault. The opponent's activity prevented him from freely castling among the soldiers tired of fighting. However, when it was reported about the spreading banners of the Republic of Poland, he decided to keep watch. The Janissary infantry and the spahis cavalry took their positions, waiting for an avalanche of horses and people to move towards them. They waited as the frost grew stronger until it finally took the first victim. Soon it was time for the second and the next ... Hussein Pasha's ranks were melting. As Kochowski wrote:

It was just dawn, our guns thundered, sending a military greeting to the Turkish camp. And then the dragoons followed at a steady pace, and finally the domestics and the whole military crowd eagerly providing their loot for their prey.

The queen was in the first line, tall, well-built, aware of the hardships of the soldiers. But also aware of fears, and therefore, shouting over the noise of battle, calling for "in God, hopefully, boldly follow!" . The Hetman led the infantry to the embankment "with a pistol shot" and here he yielded to the request of the officers. He got on his horse and rode away to see that the battle continued.

The infantry attack took place where Dennemark and Motowidło had attacked the previous day. This time the impetus of the infantry was so strong that the Janissaries lasted only a quarter of an hour. Crown banners fluttered on the ramparts. Wasting no time, the excavation of the embankments began. Spades, shovels and axes played. Lumps of earth, stones and palisade beams were dumped into the moat, preparing a passage for the cavalry as such. Meanwhile Hussein Pasha, having learned about the breakthrough, sent the Janissaries to the rescue, a hard ride. The counterattack was so serious that the so far brave infantry began to break down. Quarters of an hour passed, and they continued to defend themselves, fighting for the time it took to fill the moat. They resisted!

Fight for the Turkish banner in the painting by Józef Brandt.

Armored banners stormed from behind the embankment, followed by Stanisław Jabłonowski with the hussars. From the opposite side of the Turkish trench, hetmans Pac and Radziwiłł led the "Lithuanian youth". Hussein Pasha realized that the end of the glory was coming, and rushed to flee to the bridge over the Dniester River, on which he had crossed the trains the previous day . The Turkish dignitaries followed the leader, and finally the army. The Turks "threw themselves at the bridge in a crowd, but soon they burdened it so much that it burst under the crowd of those who were escaping, and those who were on it, falling into the water, cut the escape on [s] the obstructor." By noon, the battle turned to plunder. This time domestics played the main role.

Read also:The fall of the hussars. What made Europe's best ride useless?

A victory so great and so complete

Husejn Pasha, at the head of four thousand people, rushed to Kamieniec Podolski. The dignitaries of Rumelia and Bosnia died, the commander of the Janissaries and Spahis died. The number of Janissaries killed was estimated at eight thousand, and the number of Spahis killed was also estimated at this number. About three thousand prisoners were taken. Polish banners and cannons fell into Polish hands. When Hussein Pasha was driving into the gate of the Kamieniec fortress, Te Deum laudamus was sung near Khotyn. …

The "victory so great and so complete" was due to Sobieski and his stubborn soldiers. Hussein Pasha's army ceased to exist and Sobieski was allowed to go deep into Moldova, where the new Turkish "corps" stood. The Hetman intended to beat him and, as a result, man the castles of Moldavia and Wallachia with his own army. It was an old plan that still remembered Jan Zamoyski. But nothing came of the plan. The great Lithuanian hetman Pac excused himself with hardship and did not participate in the rest of the campaign. Radziwiłł remained with Sobieski. Part of the unpaid crown army and the dignitaries also departed.

King Michael died on November 10, 1673. The throne remained empty and the election was rushed. Only a small corps of the Crown Standard-Bearer Mikołaj Sieniawski entered Moldova. However, it was too weak to achieve lasting results. Cornered and defeated by the Tatars, Sieniawski had to withdraw. It was January 1674. Meanwhile, the crown presidencies were still stationed in Chocim and Suceava. Artillery and infantry stood near Kamieniec and the blockade of the fortress began. In this way, Hetman Sobieski prepared the ground for the campaign he hoped to start next year.

The war continued with varying luck for another 20 months. After the siege of Żurawno in October 1676, a truce was concluded. The Commonwealth regained Biała Cerkiew and Pavolocz, but the majority of Podolia and Ukraine were still held by the sultan. However, the habit of paying tribute has ended. Formally, the Republic was an independent state again.

The text was originally published in the book "Polskie triumfy. 50 glorious battles in our history ” . Learn about the clashes that changed the course of history with this richly illustrated publication. From the victorious battles in the times of Bolesław the Brave to the fierce battles of the Second World War.

Find out more:

- Derdej P., Kamieniec Podolski 1672 , Bellona, Warsaw 2009.

- Górski K., History of Polish Driving, Bookshop of Spółka Wydawnicza Polska, Kraków 1894.

- Kochowski W., Annals of Polish Climatology IV covering the history of Poland under the reign of King Michael , from Latin crowd. Polish edition J. Bobrowicz, Leipzig 1853.

- Korzon, T., History of wars and military in Poland , Ossolineum, Lviv 1923.

- Orłowski D., Chocim 1673 , Bellona, Warsaw 2007.

- Diaries to the times of King Jan III , pub. WL Markowski, Krakow 1883.

- Podhorodecki L., History of Lviv , Volumen, Warsaw 1993.

- Wójcik Z., Jan Sobieski , Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Warsaw 1994.