The image of Spartacus has long been absorbed by contemporary pop culture and has been milled into wholesale amounts of books, comics, movies and games. But after all, his rebellion was only the last of a series similar to which tormented Rome in the fall of the Republic. Neither the biggest, nor the bloodiest, and certainly ... the least successful.

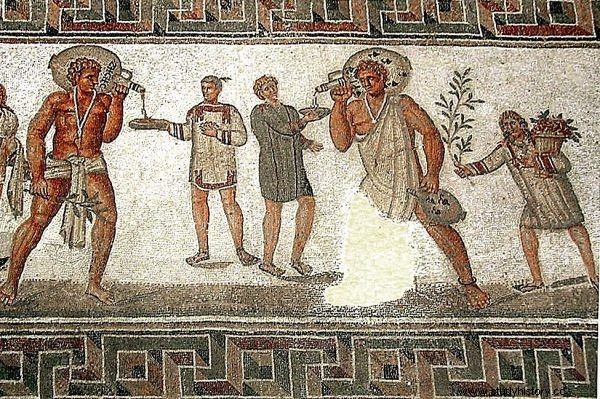

It started in Sicily. This province in the 30s of the 2nd century BCE it was called the granary of Rome for a reason. From there, tons of wheat, grape olives and, of course, wines flowed to the patrician tables, and local quarries provided raw materials for the intensively developing city. The key value was the price. It was kept low by the use of tens of thousands of slaves.

They were a cheap commodity because they were captured in bulk during numerous wars and ordinary hunts, so no one bothered too much about their physical condition - it was cheaper to replace a slave than to maintain it well. Diodorus, a historian writing less than fifty years later, described very vividly how it influenced the mood of the slave community:

The owners burdened the slaves with all kinds of work, but did little to feed and dress, so a large proportion of the slaves made their living by plundering and committing many murders, as if there was an army in Sicily highwaymen scattered all over the island (…).

Slaves in Sicily had to work hard, but they could not even count on decent food. Under such circumstances, the bloody rebellion was only a matter of time (photo:Pascal Radigue; lic. CC BY 3.0).

They started by killing lonely travelers on the roads. They then proceeded to raid with gangs on the estates and houses of owners who did not have the strength to defend them, seized them by force, looting and killing all who dared to oppose .

The man who wanted to be king

This somewhat barbaric chaos changed when a certain Eunus appeared on the stage - a mysterious figure, but certainly charismatic and talented, and above all sensing the subtleties of contemporary social engineering as hardly anyone else. He was well aware that most of the Sicilian slaves, like himself, came from the lands of Persia, where mysticizing religious ferment made people extremely susceptible to belief in magic, omens, prophecy, signs and miracles.

He knew and used this knowledge; he introduced himself as a soothsayer having direct contact with the gods, as proof of which, when he spoke ... sparks were to be emitted from his mouth. According to Diodorus, the trick was to use a nut shell and a little heat: then he put it in his mouth and blew it - sometimes sparks, sometimes a flame - the historian wrote.

But Diodorus was educated, he wrote from a distance, and he was a Romanized Greek. For the average Persian in those days, "sparkling words" was proof enough of a close intimacy with the heavenly pantheon. Eunus, on the other hand, was not only talented and charismatic, but also ambitious. Soon he organized a group of several hundred armed slaves around him and started the uprising by attacking the city of Henna.

After capturing the settlement, slaves who had fled from nearby estates started arriving in the ranks of his insurgent army. Within a few days their number grew to as many as six thousand people. Diodor related:

Entering their homes, they committed many murders and did not spare even the babies, but by tearing them from their mothers' breasts, they shattered to the ground. And no words of what they allowed themselves to the women and how they acted wickedly, and in front of their husbands .

Monument to Eunus in Enna, Sicily (photo:Eannatum; license CC BY-SA 3.0).

The insurgents' success was complete. Successive Roman expeditions sent to suppress the rebellion were crushed to dust. Eunus was followed by the leaders of local uprisings elsewhere in Sicily, and as a result he soon had enormous strength, about 200,000 soldiers. So Sicily liberated itself from the power of Rome and was able to maintain its independence - it became a separate state, headed, of course, by the leader of the uprising himself.

He understood perfectly well that, convinced of the divine origin of royal power, the Persians would require certain rituals, signs and symbols. His court was taken over by the elaborate and sumptuous ceremonies of the Seleucid monarchy - power was symbolized by a tiara on his forehead, Eunus surrounded himself with a thousand-strong guard, he announced the spouse of the goddess Atargatis and he has not stopped practicing magic.

Sicily was called the State of Novosirsk, in whose circulation even a coin with the image of the "divine" monarch appeared. And most interestingly, the independence of the Novosirsk State lasted for the entire five years!

An image of the goddess Atargatis from the 17th century "Oedipus Aegyptiacus" by Athanasius Kircher. It was her spouse that Eunus announced (source:public domain).

Its existence ended only in 132 BCE. expedition of consul Rupilius. Diodorus describes the capture of one of the main insurgent strongholds, Tauromenion, as follows:

And by encircling the insurgents he led them to unspeakable misfortune, so that they began to devour children, then went to women, and then ate each other without sparing each other (...) and finally, when the Syrian Serapion had surrendered the stronghold by treason, the praetor seized all the escaped slaves in the city and ordered them to be tortured and thrown off the rock. And from there he went against Henna and besieged her in a similar way .

King Eunus escaped with a small army and took refuge in the mountains. But not for long. He was thrown in prison where his body ate lots of lice - with some relief, but not without regret, Diodorus noted down.

The whole Iliad of misfortunes

The death of Eunus only silenced the anxiety. For the following years, the Empire trembled, then exploded again three decades later, and again in Sicily. As Diodorus noted:

Before the Sicilian slave uprising in Italy, there were a great many short slave uprisings and plots, as if the gods themselves were thus foreshadowing a huge new movement in Sicily .

Thirty years after the Eunus rebellion was put down, another slave revolt broke out in Sicily. And this time it was caused by greed of local latifundists bordering on stupidity (photo:Jun; lic. CC BY-SA 2.0).

Like the first time, so now, 104 B.C.E. the root cause of the conflict lay not so much in slavery, which was then natural for everyone and was supposed to be for many centuries, but in the greed of local latifundists bordering on stupidity, who over-tightening the screw on their "talking tools".

Discontent was widespread and channeled initially in the spontaneous revolt of 4,000 slaves in Capua, only to spill overnight across the island in a series of small, as yet unorganized, but generally effective, performances. Certainly also bloody, since Diodorus, indulgent to the rebels, describes them as a period of general confusion and the whole Iliad of misfortunes .

As thirty years earlier, it soon became apparent that the slaves of Rome were not at all savage barbarians as they were meant to be viewed. Local leaders of the uprisings efficiently disciplined their subordinates, but they themselves reached an agreement and then handed over power to a certain Salvius.

And here's an interesting thing - the further scenario of events in many places is almost identical to the one we have already learned. Salwiusz also specialized in divination, and in addition, being a skillful actor and psychologist, he developed a pompous courtly ceremonial to convince his subjects of his supernatural power. He also proclaimed himself king by divine bestowal.

Subsequent events indicated that the gods did indeed keep an eye on him. After a year of relative peace and arranging the affairs of the young state, the seventeen-thousand-strong army from Rome arrived in Sicily, which was soon crushed by the successor of the late Salvius, an exceptionally talented leader of Athenion. The next two attempts to regain Sicily by Rome brought victories to the insurgents - and so easy that the leaders of the next offensive, Lucullus and Servilius, were accused of taking a bribe and sentenced to banishment.

Sicily, mocking the power of the Empire, was becoming a salt in the eye of the Senate. A desperate step was taken - despite the fact that at the same time an army of the Germanic Cimbrians was moving through the Alps, the consular army of Aquilius was recalled from this area and directed to the island. The move was extremely risky, but it turned out to be a hit. As Diodor notes:

Of them, Aquilius was sent as a leader against the insurgents who, thanks to his personal valor, won them a great battle. And having met the king of the rebels, Athenion himself, he fought heroically with him. He killed him and suffered a head wound which he healed .

The events in Sicily were so much a salt in the eye of the Senate that it was decided to send the consular army of Aquilius to the island. And all of this at a time when the Empire was threatened by an attack by the Germanic Cimbri. The illustration shows a 19th-century fresco by Cesare Maccari depicting the image of the Roman Senate (source:public domain).

In 101 BCE the Sicilian state eventually ceased to exist. Rome has secured its peace from the rebellious island… But again only for 30 years.

Stations of the Cross

In the context of both Sicilian revolts, the famous Spartacus uprising seems barbaric, chaotic and sometimes simply stupid, although Spartacus himself was admired not only by the Romans as a capable leader, but also as a man of high culture. Plutarch wrote about him:

[ / em> .Here in 73 BCE, a small group of 80 gladiators from the Capua school decided to escape. They were trained, they could fight, so they escaped without any major problems, although they had only rushed kitchen knives and spits at their disposal.

Monument to Spartacus in the Bulgarian city of Sandanski (photo:Grantscharoff; license CC BY-SA 3.0).

They also easily defeated the first squad of soldiers sent against them. As a result, they obtained enough armor and weapons to continue the fight. But not only that helped them. As Plutarch writes: Now they were joined by many local shepherds of oxen and sheep, brave and agile swindlers, some of whom they armed and some used for communication and as light-armed .

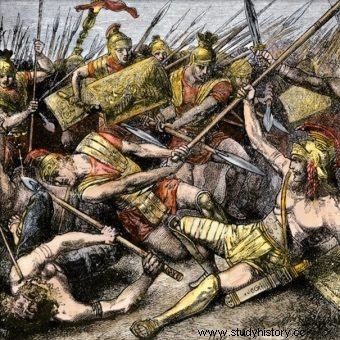

Spartacus' army grew rapidly, absorbing hundreds of escaped slaves, but also the local poor and common scum. It was a chaotic, multi-ethnic, but powerful force - it easily wiped out all the Roman troops sent against it. Even the most elite ones under the command of Cossynius and Varynius. In the spring of 72 BCE the uprising already covered all of southern Italy.

Spartacus' plan was simple and most importantly - completely doable. Trak intended to break through towards the Alps, cross them and dissolve the army so that each of the slaves could return to their homeland. It had no strategic goals, the only one was freedom. But [his] people quantitatively strong and confident in their power did not obey, went to Italy and wreaked havoc everywhere Plutarch wrote.

Plutarch was sure that if Spartacus managed to get to Sicily, a new slave uprising would surely break out (source:public domain).

Single troops separated from the main army of Spartacus, the sole purpose of which was plunder. And they were not small forces - the unit of a certain Kriksos had, for example, about 20,000 people, almost all of whom died on the battlefield, literally massacred by the publi consular army. Despite this, the core of Spartacus' forces was still strong enough that he soon retaliated against Rome, destroying not only the Publoli army at Pinaceum, but also the second consular army sent to help.

It is very likely that at this point, the slaves would be able to take over the capital of the Empire, and certainly implement the original plan to break through the Alps. For unclear reasons, Spartacus decided to turn back south and cross to ... Sicily. He probably wanted to create his country there, like his predecessors. The moods favored it. Two thousand armed men would be enough for a slave war to flare up again, a spark would be enough for it to break out - admitted Plutarch.

The plan, however, was not implemented and in the vicinity of Apulla, Spartacus had to accept a decisive battle with the forces of Crassus. As Plutarch writes:

[Spartacus] lined up his men in battle formation and was immediately given a horse. (...) Then he wanted to break through the terrible fight and wounds straight to Crassus. But it didn't get to him. He killed two centurions with whom he collided. In the end, when all his people fled, he was left alone:surrounded by many, defending himself bravely, he was stabbed .

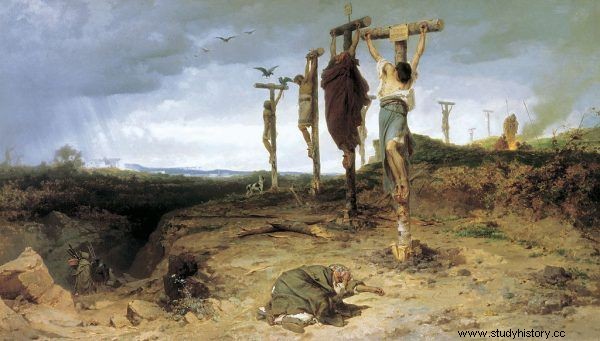

After the fall of the Spartacus uprising, 6,000 of its participants were crucified along the Via Appia. The picture shows a painting by Fyodor A. Bronnikov (source:public domain).

And with Appian we find the continuation of the battle: The rest of his army in disarray, piled up, so that they were murdered in countless numbers .

Some survived, but only to be hung on six thousand crosses lined up along the Via Appia. I wonder what the outcome of this last slave war would have been if it had ended in Sicily? Or maybe that's what happened? The body of the slave chief has never been found, and according to Suetonius, even in 63 BCE. August's father was to be sent to fight the remnants of Spartacus' bands .. .