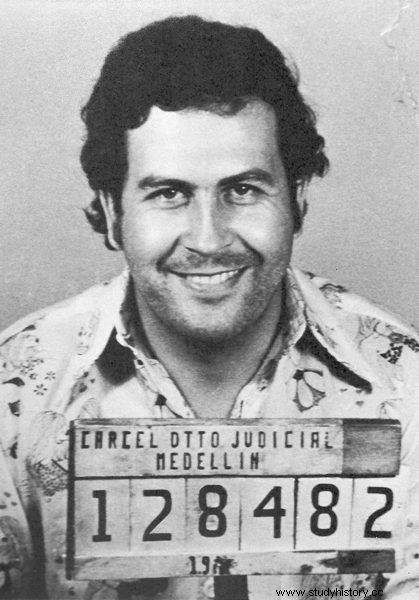

"Plata o plomo" - "silver or lead" - the life maxim of Pablo Escobar applied to everything and everyone. The Colombian drug lord had no mercy. He commissioned the murders of politicians, representatives of the judiciary, and business competitors. In 1989, he handed down a ruling on football referee Álvaro Ortega, because he severely wounded his football-loving heart.

May 31, 1989. At Estadio Nemesio Camacho El Campín in Bogota, the final battle of the most prestigious club football competition in South America - the Copa Libertadores - took place. After two matches between Colombia's Atlético Nacional Medellín and Paraguay's Club Olimpia Asunción, there is a draw (2:2) on the scoreboard. Penalty shootouts will decide the final victory.

Both teams are ineffective. They miss often. After all, after nine streaks, Leonel Álvarez is tipping the tide. Los Verdolagas become the first Colombian team in history to triumph in this competition. There is a celebration in the stands. Somewhere in the crowd, in ecstasy, the patron of Atlético Nacional jumps. His name is Pablo Escobar and he takes football - like the drug deal - deadly seriously.

Five months later. Independiente Medellín, also supported by Escobar, runs onto the pitch of the Cali stadium. In the 88th minute the hosts are leading 3:2. Pablo is inconsolable, his boys lose, but at some point he abruptly jumps off his seat. Chilean Carlos Castro scores a goal and puts a draw ... but several seconds later the referee Álvaro Ortega canceled the goal. Until the final whistle, the score will not change anymore.

Furious and offended, Escobar orders his men to find and kill the referee. Two weeks later, on November 15, 1989, the killers carry out a sentence outside a hotel in Medellín. Ortega gets nine bullets. His friend, including football referee Jesús Díaz, sees the situation. Years later, he admits that after the last shot, the murderer addressed him directly:“» Chucho «, take it easy. We don't want any more trouble. We don't want to hurt you. Then he got into the car and drove away. Díaz was still trying to revive his companion. Nothing happened. Álvaro was already dead.

Two cartels, two methods

Ortega, with his decision not to recognize the goal, offended Pablo's two great passions:football and business. How? The team from Medellín lost the game, and sadness filled the heart of 'El Patrõn', but, even worse, they lost to a club that was financially backed by Miguel Rodríguez Orejuela - head of the Cali cartel, Escobar's main drug competitor. Such an insult Pablo could not let go of.

At the turn of the 1980s and 1990s, the Medellín and Cali cartels fought for the huge cocaine market that was the North American continent. In its most prosperous era, Ecscobar controlled 80 percent of the drugs transported to the United States, Mexico and the Dominican Republic . To keep his empire in check, he ruled with a firm hand:he killed when opposed, or bribed him for obedience and submission. Everything follows the principle of "silver or lead".

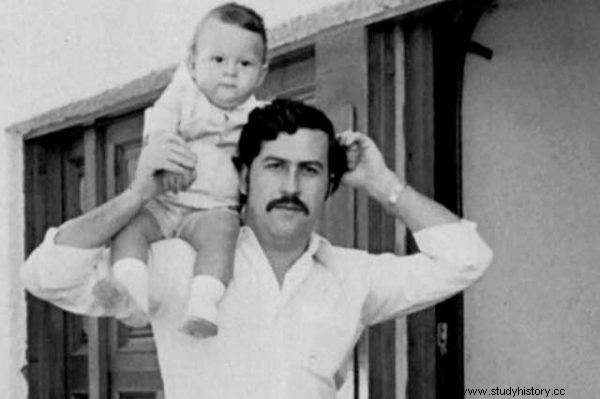

Pablo was a die-hard supporter:he was mad with joy when Atlético Nacional won and he cried as he swallowed the bitterness of defeat.

Miguel and Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela had different methods. They acted discreetly, they did not resemble typical thugs. Instead of giving away money, they put it into legal circulation. Most often with the help of companies. One of them was the football club América de Cali, in which the brothers bought their shares in 1979.

The differences between Escobar and the Orejuel duo were not only in the business sphere. The parties had a different view of football. Pablo was a staunch supporter:he was mad with joy when Atlético Nacional won and he cried as he swallowed the bitterness of defeat. But also in football he eagerly used the famous "plata o plomo" .

During the Copa Libertadores quarter-finals in 1990, his men were to influence the tie against Vasco da Gama Rio de Janeiro. Uruguayan judge Daniel Cardellino admitted he had received death threats prior to the competition and was offered $ 20,000 in exchange for helping to win the game. The Brazilians knew what was going on and protested after the final whistle. Atlético advanced to the next round, but CONMEBOL (South American football confederation) banned the organization of international matches in Colombia.

A deadly serious game

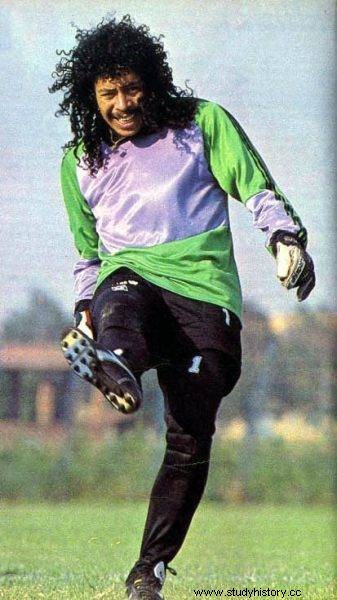

The fan Escobar donated heavily to teams from his city, built football pitches for young people, was friends with the best Colombian players, for example René Higuita - a goalkeeper who shocked the world with an intervention called a "scorpion kick". By supporting local teams, Escobar forged the first strand of links between football and the cartels, although he never officially held a managerial position. It was pure, almost childlike love.

In 1991, as a result of an agreement with the Colombian government, Pablo ended up in the "La Catedral" prison, designed and built with his own money. One of the most visited places was the local soccer field. The same to which stadium stars, headed by Diego Maradona, were invited. “We played a game and everyone had a good time. Then we had a party with the best girls I've ever seen. And it's all in prison! I couldn't believe it "- this is how" Divine Diego "recalled one of the post-match events.

Escobar was friends with the best Colombian players, for example René Higuita - a goalkeeper who shocked the world with an intervention called a "scorpion kick".

The bosses in Cali looked at football differently. Pragmatically. They were not so interested in it, they did not tear their throats in the stands and did not surround themselves with a garland of players. For them, it was a washing machine where they could wash out cocaine-spilled dollars. How? Take, for example, player transfer fees and their wages raised to amounts that would be suspiciously excessive even today.

Over time, however, the Orejuel brothers saw the irrational possibilities that football brought with it. They picked up the gauntlet thrown by Pablo. The Colombians loved to kick the ball, and you could win their favor which is why the Cali cartel invested in its club in the 1980s. Some very good players have joined La Mechita Roja, and the whole crowd has been led by coach Gabriel Ochoa Uribe.

From 1982 to 1986, América de Cali continued to win the national title, being a Copa Libertadores finalist three times. Unfortunately, she never won. His rival's successes irritated Escobar, but he enjoyed his defeats even more, so when Atlético Nacional Medellín won the South American Champions League in 1989, Pablo couldn't sit still. He gave his rivals a shot through football.

Victories, escape and death

After the killing of referee Ortega, league games were temporarily suspended. Pablo Escobar, by issuing a death sentence, took away the pleasure of watching footballers in action. He ruled and shared the cocaine market for a while. Some sources say that he earned as much as $ 28 billion a year.

Everything changed in 1992, when the Americans rushed to help the Colombians, and the people once hurt by Escobar and members of the Cali mafia founded Los Pepes. The noose around Pablo, his family and associates tightened more and more. The "king of cocaine" had to go into hiding.

While Escobar was on the run, his competitors' club was winning the national championship. Pablo knew about it. Even in such a difficult situation, he was keenly interested in football. One of his companions, John Jairo Velasquez Vasquez, known as "Popeye", mentioned in the documentary "The Two Escobars" that one day Pablo fell into a trap. Bullets flew everywhere, and as if nothing had happened, he pulled out the radio and turned on the coverage of the Colombian national team match. He obeyed, then scuttled away again.

Pablo Escobar, by passing the death sentence, took away the pleasure of watching footballers in action.

The hunt for Escobar ended on December 2, 1993 in one of the districts of Medellín. To this day, people argue about who killed him. His funeral gathered thousands of people. They said goodbye to their boss, patron and soul mate. For Colombian football, the death of 'El Patrõn' marked the beginning of the end of a golden age. The national team of this country advanced to the world championship in 1994 in a great style, it was a series winner in friendly matches and - as a small group - it united, not divided, a nation plunged in a drug war.

On the American pitches, the Colombians have failed. Even though Pele himself considered them favorites for the title, they didn't make it through the group stage. The late Pablo did not see his compatriots losing to Romania and the USA. He also did not see six bullets piercing Andrés Escobar - a footballer who sentenced himself by scoring a suicide in a match against the Americans . Officially, the cause of his murder was that fatal goal, unofficially the revenge of the mafiosi who lost a fortune to the bookmakers because of the Colombian defeat.

In 1995, the Orejuel brothers were arrested. Thus, the "Narkoderby" - the rivalry between Medellín and Cali, Atlético Nacional and America - lost their non-sporting significance. Today, surrounded by an aura of romanticism, they are an inspiration for writers and screenwriters. It is no wonder - only in Colombia football and drugs worked together so tightly.